Intro to Descartes

René Descartes (1596-1650) was a French philosopher, scientist, and mathematician. You might recognize the name if you ever learned about the x-y coordinate system in high school math, a.k.a. the Cartesian coordinate system.

He is also particularly famous for the Latin phrase “cogito, ergo sum,” meaning “I think, therefore I am.” He used that phrase in several places, but probably the most famous occurrence happens in his Meditations on First Philosophy, which we are examining here!

Descartes breaks this into six different meditations, supposedly written on six separate days during some of his free time. They style gives the impression that he is literally just writing this out for himself as he thinks about things, talking about what he can see or how he feels as he thinks over things.

The first two meditations are by far the most influential as he tries to tackle the problem of radical skepticism, trying to doubt literally everything and challenging whether we can really know anything.

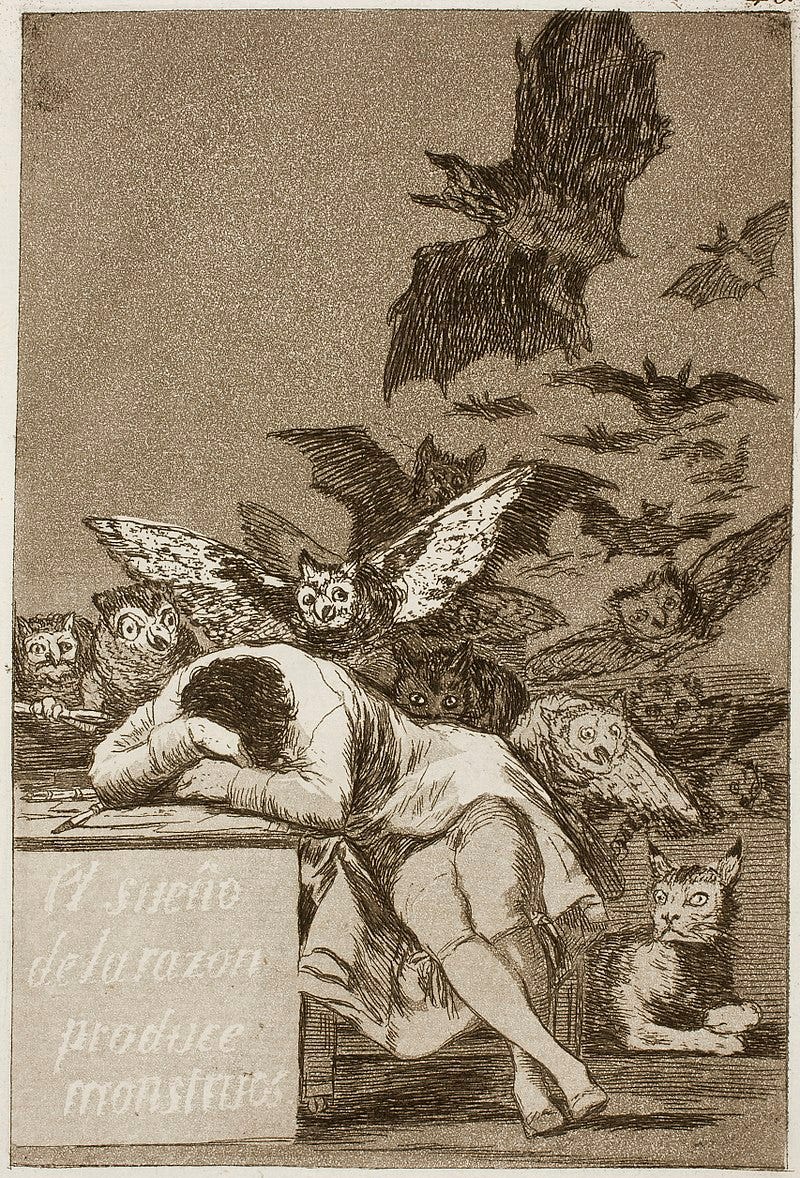

The problem here mainly comes from the kind of challenge Descartes set up for himself. If he is going to doubt everything that it is even possible to doubt, and only accept what he knows with 100% certainty, then that seems to rule out a ton of stuff. The most famous objection Descartes gives is about the “evil demon.” He asks us to imagine a powerful and evil demon who, for our entire lives, has trapped us in a dream for our entire life, so that everything we see, hear, touch, etc. are all part of its illusion. A modern equivalent might be something like the movie The Matrix.

This doesn’t strike most of us as a very likely scenario, but it’s also one that isn’t strictly speaking logically impossible. If our standard is to withhold belief from something if we can raise even the slightest doubt then, he has succeeded in doing that here.

Still, he finds he cannot eliminate all of his beliefs this way. Most notably, even if a demon is constantly tricking him, there must still be a “him” to be tricked! This leads to his famous argument “I think, therefore I am.”

Descartes wasn’t the first person to make this kind of argument. Notably, Augustine of Hippo had made a very similar argument over a thousand years earlier. However, Augustine buried this argument deep within his gargantuan text The City of God. It can be found specifically in Book 11, Chapter 26:

But, without any delusive representation of images or phantasms, I am most certain that I am, and that I know and delight in this. In respect of these truths, I am not at all afraid of the arguments of the Academicians, who say, What if you are deceived? For if I am deceived, I am. For he who is not, cannot be deceived; and if I am deceived, by this same token I am. And since I am if I am deceived, how am I deceived in believing that I am? For it is certain that I am if I am deceived. Since, therefore, I, the person deceived, should be, even if I were deceived, certainly I am not deceived in this knowledge that I am. And, consequently, neither am I deceived in knowing that I know. For, as I know that I am, so I know this also, that I know. And when I love these two things, I add to them a certain third thing, namely, my love, which is of equal moment. For neither am I deceived in this, that I love, since in those things which I love I am not deceived; though even if these were false, it would still be true that I loved false things.

For Augustine, this point is another way to find an image of the Trinity within human nature. For Descartes, this is a much more central question, and the starting point of the rest of his project in philosophy.

Descartes only begins with this problem of skepticism though in the hopes that he can work his way out of it. The problem here seems extreme, but he is also confident that he has a way to ground his beliefs on actual certainty. Whether he succeeds here is another question.

Descartes’ influence here cannot be overstated, and is largely considered one of the first, if not the first, figure of modern philosophy. His method and approach to philosophical questions, and especially his focus on method here, became extremely influential, even on people who disagree with him but needed an effective way to challenge him. This often leads to epistemological divides, such as that between the “rationalists” like Descartes and Baruch Spinoza against the “empiricists” like John Locke or David Hume.

The later meditations try to examine other questions, like the existence of God, which is interesting but not quite as impactful. It is important to keep in mind that Descartes was also writing in the deeply Catholic France at the same time as Galileo Galilei, so authors had to be careful around what exactly they published. Still, it seems to me like Descartes’s belief in God was sincere. However, the role God plays in his philosophical system is so abstract that it is detached from any real religious or dogmatic conclusions.

I will try to recreate the main points of Descartes’ arguments here, keeping things reasonably close to his own view. Since he wrote in the first person perspective, I will try to adopt a similar approach in my summary, although the claims here should mainly be viewed as Descartes’ and not my own. Part of the point of the style though is for the reader to imagine themselves in his same position and going through the same chain of reasoning though, so this changes little.

Meditations on First Philosophy

First Meditation: On What Can Be Called Into Doubt

When I think back over my life, I realize that I have believed many false things before, and often for very bad reasons. To solve this problem I have decided that, at least once in my life, I should put all of my beliefs to the test.

I could try to do this by examining each thing I believe one-by-one to see if I can prove it false, but that doesn’t seem realistically possible. Instead, I’ll go the other way around. If I can find any reason at all to doubt one of my beliefs, I will reject it. That way I can reestablish the things I know for certain, and build my other beliefs on a firm foundation.

So all I need, for the purpose of rejecting all my opinions, is to find in each of them at least some reason for doubt.

The majority of my beliefs come from my senses (i.e. sight, sound, etc.). But my senses have deceived me about some things before, so it’d be unwise to put complete faith in them.

Still, my senses seem more reliable about some things than others. I might get some details wrong if something is small or distant, but I can see other things clearly, like that I am sitting down and working on this paper.

To take a more extreme example, could I doubt that these hands or this body is mine? To seriously doubt that I’d have to make myself like someone with a serious mental illness, suffering from severe delusions.

Yet there are still times when I have gotten that wrong! When I sleep, I sometimes dream that I’m doing some very familiar activity, when really I’m lying down in my bed! I’m pretty confident I’m not asleep right now though. My eyes are wide awake and my actions are deliberate. I have a kind of clarity right now that I do not when I am asleep.

Still, the more I think about it, the more it seems like there is no perfect method for determining whether I’m awake or asleep. And if I’m doubting everything it is possible to doubt, then that seems to have very serious implications.

Maybe I’m not actually sitting here and writing this. Maybe I don’t even have hands or a body at all.

But dreams are kind of like paintings, acting as impressions of real things. When an artist draws a siren or a satyr, they take real animals and jumble them up. Or even when they do think of entirely new animals, at least the color in the picture is real.

Likewise, since I may be dreaming, I cannot know if my hands are real, or if “hands” really exist at all, I should at least know that the elements that make up these mental pictures are real.

These elements here appear to be things like body and extension, as well as the shape of things extended. It also includes quantity, size, and number, as well as place and time.

This has some serious implications about the things I can know. Having pushed our doubts this far, it seems like I can throw out all physics, astronomy, medicine, etc. All of that could just be part of my dream.

But there are other things I can know are true, even if I am dreaming, namely math and geometry. Even in a dream, two plus three equals five, and a square will have four sides. Surely I can’t call such basic and obvious truths into doubt.

Then again, maybe there is a way to doubt it. I have long heard about the existence of an all-powerful God who is supposed to have made me. Any being that powerful could surely deceive me about all sorts of things.

How do I know that he hasn’t brought it about that there is no earth, no sky, nothing that takes up space, no shape, no size, no place, while making sure that all these things appear to me to exist?

It’s been said this God is supposed to be supremely good, so maybe he wouldn’t let me get fooled this way. But if that were true, why doesn’t this same God let me ever get things wrong? Clearly I am deceived sometimes, and nothing seems to necessarily rule out applying that here too.

Some people don’t believe in God at all, but that hardly seems to solve this problem. If my creator is less perfect, that makes it more likely that I have imperfections too and might be deceived all the time, not less.

It seems like I’m stuck then. If I only accept things I can be completely certain of, with no room for doubt, I have to hold back from affirming even these basic beliefs.

Despite saying that, I’m actually have a very hard time doing that. Believing in some of these things is so basic, natural, and habitual, I can’t help myself and need to keep reminding myself of this reasoning. If I’m going to break this habit and believe things for right and certain reasons, then I’m going to at least pretend like I don’t believe them, at least for a little bit. I don’t want to bring any harm to myself though, so this pretending won’t change how I behave, and only just how I’m acquiring knowledge.

To put this objection in its most extreme form, I can say that this trickery is being done by an evil demon. (It doesn’t seem appropriate to say God, who is perfectly good and the source of truth, is deceiving me.) Everything I sense are mere illusions created by this demon, who is as powerful as he is cunning.

To fight against such a deceiver, learning the truth may be impossible, but I could at least guard against falsehood by refusing to assent to their tricks.

So I shall suppose that some malicious, powerful, cunning demon has done all he can to deceive me – rather than this being done by God, who is supremely good and the source of truth. I shall think that the sky, the air, the earth, colours, shapes, sounds and all external things are merely dreams that the demon has contrived as traps for my judgment. I shall consider myself as having no hands or eyes, or flesh, or blood or senses, but as having falsely believed that I had all these things. I shall stubbornly persist in this train of thought; and even if I can’t learn any truth, I shall at least do what I can do, which is to be on my guard against accepting any falsehoods, so that the deceiver – however powerful and cunning he may be – will be unable to affect me in the slightest.

Holding off my old opinions is actually pretty hard work. It’s easy to fall back to them, since the task I’ve set for myself is so daunting.

Second Meditation: The Nature of the Human Mind, and How it is Better Known than the Body

According to yesterday’s meditation, I am going to set aside all of my beliefs that I can raise even the slightest bit of doubt for, treating it as if I proved it false. I was to do this until I found something absolute certain, which I cannot raise any doubts about at all, or perhaps found that certainty about anything was impossible.

The ancient Greek mathematician Archimedes once said that with a fixed point and a long enough lever he could lift the world. Likewise, I hope that I can accomplish great things here if I can find at least one thing about which I can be certain.

Because of the dream and demon objections, I found that I cannot have absolute certainty in my senses.

If I have found that everything I see is an illusion, isn’t it still true that I am the one seeing them? Even if these thoughts were created by God or something else, or by myself, surely I still exist to have these thoughts in the first place!

This is a bit confusing because one of the things I doubted was whether I really had a body at all. But it seems like I am so mixed together with my body and my senses that I couldn’t exist without them. But even if I convinced myself that there is no sky, no earth, no minds, no bodies, I know I still exist since, if I am around to be convinced about things, then I must be!

But what about the demon? Even in that case, if it is tricking me, I must still exist to be tricked! I think, therefore I am.

But there is a supremely powerful and cunning deceiver who deliberately deceives me all the time! Even then, if he is deceiving me I undoubtedly exist: let him deceive me all he can, he will never bring it about that I am nothing while I think I am something. So after thoroughly thinking the matter through I conclude that this proposition, I am, I exist, must be true whenever I assert it or think it.

I have at least one fact that is certain then.

But what is this “I”? I don’t want to assume more than I have actually proven and slip back into my old habits. I should only believe things about myself that are similarly unshakably certain.

Before I believed I was a “man” and had a number of features like a face, arms, feet, and so on. In short, that I had a body. I also believed that I did things like eating, drinking, walking, perceiving, and thinking. These I attributed to the soul.

The soul seemed to me like a thin thing, like fire or wind, which permeated the more solid body. I had a better conception of the body though, which had a definite shape and position, could be perceived, and could be moved.

Intuitively, it seems like I should say that the body could only be moved by things bumping into it. An amazing thing about the human body though was that it was able to initiate its own movements, and could sense and think. These don’t seem like features shapes should have.

I should consider this in the context of the demon objection though. If everything I see is an illusion, I can’t really be certain of these things about myself. If I am supposing I don’t have a body or soul, then I don’t seem to have any of these features.

That is, all except one: thought! I think, therefore I am. But how long do I exist? So long as I am thinking, at least, but perhaps no more than that. If I stopped thinking, I might stop existing. I can’t be certain.

I have one answer then to what “I” am then: a thinking thing.

Strictly speaking, then, I am simply a thing that thinks – a mind, or intelligence, or intellect, or reason, these being words whose meaning I have only just come to know. Still, I am a real, existing thing. What kind of a thing? I have answered that: a thinking thing.

What else am I? I have supposed that there are no bodies or souls, so I can’t say I am that, although maybe I’ll discover that I am later.

My knowledge of what I am cannot depend on my imagination, precisely because it invents things. Imagining is simply contemplating bodily things, and I have to view anything involving bodies with suspicion.

What do I do as a thinking thing then? I doubt. I understand. I affirm, deny, want, and refuse. I also imagine and I sense, even if these are mere illusions. Even if I am stuck in a perpetual dream, all of this remains true. That I doubt it so obvious that even trying to doubt it just affirms it. And even if everything I see is part of the dream, it is still true that I see it.

Because I may be dreaming, I can’t say for sure that I now see the flames, hear the wood crackling, and feel the heat of the fire; but I certainly seem to see, to hear, and to be warmed. This cannot be false; what is called ‘sensing’ is strictly just this seeming, and when ‘sensing’ is understood in this restricted sense of the word it too is simply thinking.

Despite all this, and that I know that my own existence is more certain than the existence of bodies, this “I” remains more of a mystery to me than bodies which I can so easily imagine. The temptation to fall back into error remains.

Fine then. I can indulge it for a moment, and consider one particular body: a piece of wax taken from a honeycomb.

Using my senses, I can say a few things about how it seems to me. It tastes like honey and has the scent of flowers. I can clearly see its color, shape, and size. When I touch it, it is hard and cold, but easily handled. When I tap it with my knuckle, it makes a sound. I have thoroughly examined it as a body then with all my senses.

But if I hold this wax to the fire, it changes entirely!

The taste and smell vanish. It turns to a different color. The shape is lost, the size increases, and it becomes liquid and hot. It no longer makes a noise when I tap it.

Despite all these changes, I want to say that it is the same wax. But if it lost every property that it had before, what did I understand so clearly about it? If I take away all these things, what I am left with is that it is “something extended, flexible and changeable.”

What do I mean by flexible and changeable here? I can imagine the wax changing shape between triangles and squares, sure. But what I really mean is that it can go through endless changes of this kind; far more than I can imagine. What do I mean by extended? It seems to be the actual size of it, which can change like when it melts.

This understanding of what the wax (i.e. something extended, flexible and changeable) is I gained, not from my imagination, which changed on every point and cannot go through the infinite changes possible to it. Instead, this understanding came from my mind.

It is so easy for the mind to go astray like this! If I see the wax right in front of me, I want to say that I come to know it through my senses. But now I have examined it in a way only possible for the mind.

If I can see (or think I see; I am not distinguishing the two) the wax, then surely I also see myself even more intimately. If my perception of the wax establishes that it exists in some sense, even if only as an illusion I perceive, I am quite certain that I exist.

Just as I came to understand the wax more clearly through my mind, I can also come to understand myself.

Thanks for reading! If you would like to support me, you can help buy me a Ko-Fi!