Introduction

A while ago, I read through historian Robert Paxton’s wonderful book The Anatomy of Fascism. The book is essentially an attempt at trying to construct the most accurate and grounded definition of fascism possible, which is an extremely important thing to have on hand when identifying modern fascist movements. I am thoroughly impressed with Paxton’s work as a piece of historical scholarship, and the case he makes is extremely convincing.

If I do have a point of criticism, it may be because of his more academic liberal tendencies which can leave him so focused on past fascistic movements that he nevertheless has difficulties or hesitancy to identify modern movements we can clearly identify as fascist. Notably, Paxton had hesitated to identify Donald Trump as a fascist until the events of January 6th, 2021, preferring to put him more in the general ‘bucket’ of authoritarianism. Wanting to avoid misuse of fascism is understandable, but the signs were clearly there well before the attack on the US Capitol. If you can’t recognize a fascist until after they’ve been president for four years, you’re doing something wrong.

That being said, I will still be largely presenting Paxton’s argument here, rather than my own, and hope my representation is faithful. This will likely be divided into several posts. I start here with Chapter 1: Introduction.

The Invention of Fascism

Fascism is new to the 20th century

Fascism was the major political innovation of the 20th century. Other prominent currents of conservatism, liberalism, and socialism rose to prominence in the 18th and 19th century. But fascism wasn’t understood even at the end of the 1800s.

Fascism challenged socialist expectations. Engels had believed that, with the expansion of voting rights, socialist victory would become inevitable. Popular support would lead to growing political power, which would then force the hand of conservatives to abandon legal pretexts to challenge an enthusiastically leftist population. Fascism upended this assumption.

Dictatorship against the Left amidst popular enthusiasm - that was the unexpected combination that fascism would manage to put together one short generation later.

There had been some premonitions of a future fascism by people like Alexis de Tocqueville and Georges Sorel, recognizing the dangers of democracy as leading to a new kind of tyranny or a revolution against “liberal decadence” leading to greater social conservatism.

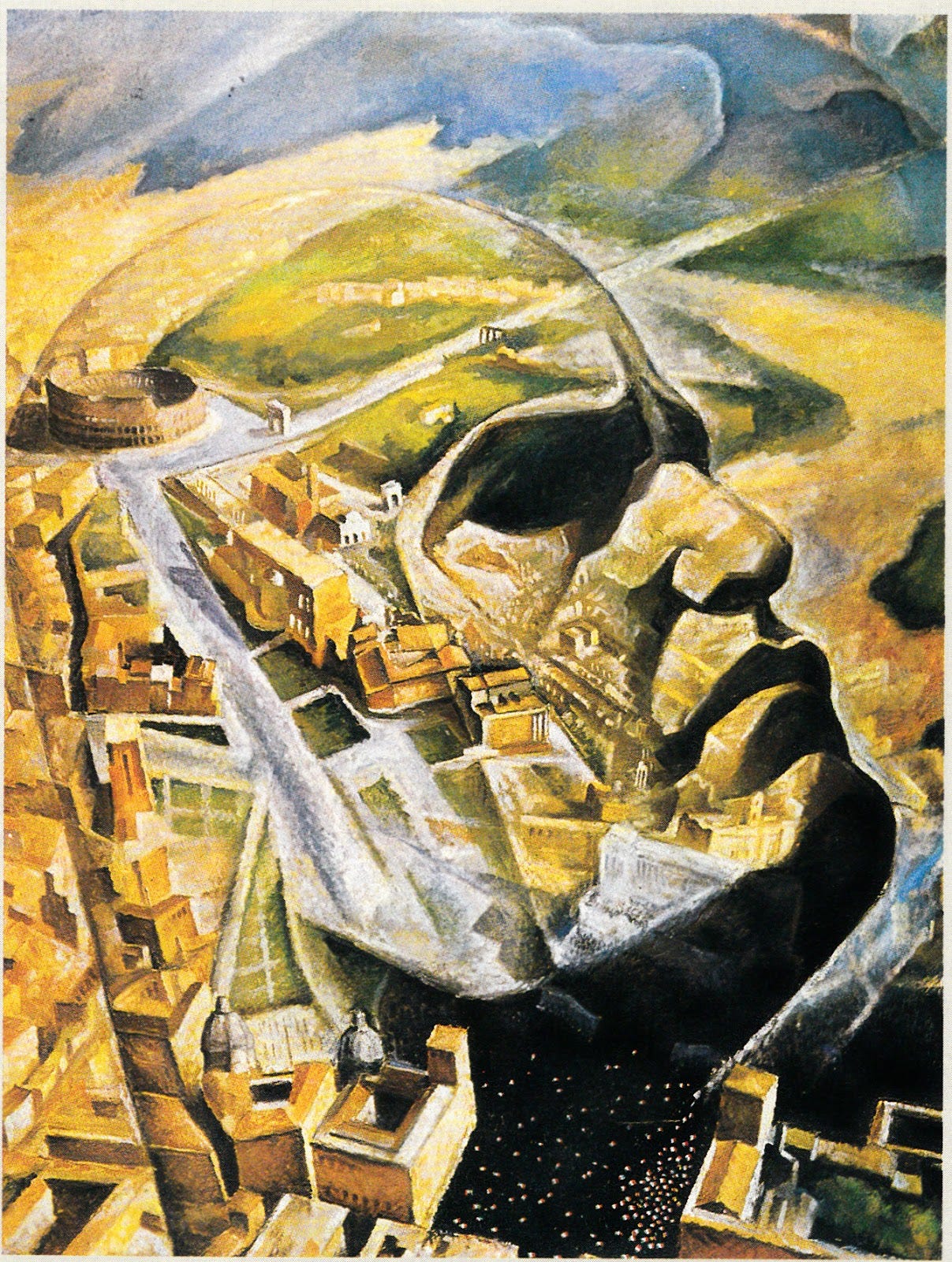

The fasces was used long before fascism

The word “fascism” comes from the Italian fascio, meaning a bundle of sticks. It is meant to recall the image of the Latin fasces, where an axe is encased in a bundle of rods, which was used as a symbol of authority in the Roman empire.

Ironically, prior to 1914, the fasces was often used as a left-wing symbol as a general symbol of unity or solidarity, as well as having other popular uses. Here are some examples:

Several left-wing groups named themselves after the fasces as well. In 1893, a peasant revolt against landlords called themselves the Fasci Siciliani.

Mussolini started using the term fascismo to describe his pro-war syndicalists and ex-soldiers at the end of World War 1. But he still had no monopoly on the term at that time.

The first impression of fascism

Fascism officially began in Milan on Sunday, March 23, 1919, when a group of over 100 war veterans, pro-war syndicalists, futurists, and others met at the Milan Industrial and Commercial Alliance to “declare war against socialism… because it has opposed nationalism.”

Two months later they issued the Fascist program, aiming to combine their veterans’ patriotism and radical social experimentation for a kind of “national socialism,” as well as calling for military and expansionism, mixed in with some democratic and populist anti-capital and anti-clerical goals.

Mussolini’s movement was not limited to nationalism and assaults on property. It boiled with the readiness for violent action, anti-intellectualism, rejection of compromise, and contempt for established society that marked the three groups who made up the bulk of his first followers - demobilized war veterans, pro-war syndicalists, and Futurist intellectuals.

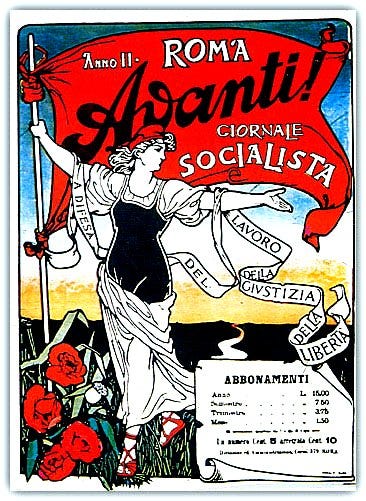

On April 15, 1919, soon after fascism was established, Mussolini’s friends invaded the office of the socialist daily newspaper Avanti, which Mussolini had been an editor of from 1912 to 1914. They smashed its presses and equipment, killing four, and injuring thirty nine.

Italian Fascism thus burst into history with an act of violence against both socialism and bourgeois legality, in the name of a claimed higher national good.

Three years later, Mussolini’s Fascist party would be in power in Italy. Eleven years after that, another fascist party would be in power in Germany. Another six years later, Hitler plunged the world into war.

Fascism was broadly thought of by liberals as a kind of government of “common scum,” or an “onagrocracy,” i.e. a government by braying asses. They thought fascism would be a “parenthesis” in Italian history. Fascism was seen as a symptom of moral degeneration, which would be fixed by rule of the “best men.”

Others knew something deeper was at play. Socialists were used to thinking of history as an unfolding of economic systems. They had a definition of fascism at the ready as “the instrument of the big bourgeoisie for fighting the proletariat when the legal means available to the state proved insufficient to subdue them.” Under Stalin, it became communist orthodoxy that “Fascism is the open, terroristic dictatorship of the most reactionary, most chauvinist and most imperialist elements of finance capital.”

No definition has been able to get universal assent however. Fascism was so varied, some doubt it means anything but a smear word.

The goal of this book is to rescue a meaningful use of fascism, with its attractiveness, historical path, and ultimate horror.

Images of Fascism

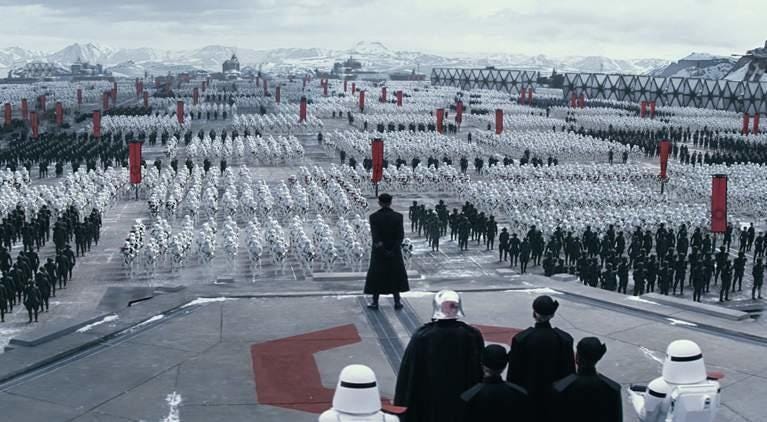

Fascism is visually simple, but deceptively complex

People think they know what fascism is because they know what it looks like.

But this is an image that was carefully constructed by fascist propagandists, and helps serve fascism by individualizing it to the fascist leader, who can then be scapegoated to let the people and nations that supported it off the hook.

The image of the all-powerful dictator personalizes fascism, and creates the false impression that we can understand it fully by scrutinizing the leader alone. This image, whose power lingers today, is the last triumph of fascist propagandists. It offers an alibi to nations that approved or tolerated fascist leaders, and diverts attention from the persons, groups, and institutions who helped him. We need a subtler model of fascism that explores the interaction between Leader and Nation, and between Party and civil society.

Fascist reality is more complicated.

Anti-semitism is not essential to fascism

Mussolini’s fascism did not seem particularly anti-semitic until sixteen years after its founding, and even had Jewish supporters and backers. Two hundred Jews participated in the March on Rome.

Likewise, there can be extremely anti-Semitic governemnts that are better described as authoritarian rather than fascist, such as Marshal Patain’s collaborationist government in Vichy France.

Fascism’s “anti-capitalism” is anti-globalist, not socialist

Fascism is not essentially anti-capitalist. Early fascists spoke this way, denouncing greed, “international finance capitalism,” and promised to seize property for their supporters. They denounced capitalism almost as loudly as socialists did.

But their rhetoric contradicts their actions.

Whenever fascist parties acquired power, however, they did nothing to carry out these anticapitalist threats. By contrast, they enforced with the utmost violence and thoroughness their threats against socialism. Street fights over turf with young communists were among their most powerful propaganda images. Once in power, fascists banned strikes, dissolved independent labor unions, lowered wage earners' purchasing power, and showered money on armaments industries, to the immense satisfaction of employers.

This has led scholars to debate if fascism is genuinely anti-capitalist. Some take their rhetoric seriously, and say it is. Others, and not just socialists, see fascism as defending “capitalism in decline.”

We must understand both words and action. The anti-capitalist language is part of fascism’s appeal, but this is an anti-capitalism of a special kind. Unlike socialism’s focus on worker exploitation, fascism was focused on the “globalism” of capitalism, which went against their nationalism.

Even at its most radical, however, fascists’ anticapitalist rhetoric was selective. While they denounced speculative international finance (along with all other forms of internationalism, cosmopolitanism, or globalization - capitalists as well as socialist), they respected the property of national producers, who were to form the social base of the reinvigorated nation. When they denounced the bourgeoisie, it was for being too flabby and individualistic to make a nation strong, not for robbing workers of the value they added. What they criticized in capitalism was not its exploitation but its materialism, its indifference to the nation, its inability to stir souls. More deeply, fascists rejected the notion that economic forces are the prime movers of history. For fascists, the dysfunctional capitalism of the interwar period did not need fundamental reordering; its ills could be cured simply by applying sufficient political will to the creation of full employment and productivity. Once in power, fascists regimes confiscated property only from political opponents, foreigners, or Jews. None altered the social hierarchy, except to catapult a few adventurers into high places. At most, they replaced market forces with state economic management, but, in the trough of the Great Depression, most businessmen initially approved of that. If fascism was “revolutionary,” it was so in a special sense, far removed form the word’s meaning as usually understood from 1789 to 1917, as a profound overturning of the social order and the redistribution of social, political, and economic power.

Fascism is only “revolutionary” in a non-standard sense for how it turned previously private matters into public concerns, turning citizenship from a legal status into something requiring enthusiastic conformity. This sometimes put it into conflict with conservatives, while at other times it united with them against the Left. This complicated relation means that fascism cannot be considered “simply a more muscular form of conservatism, even if it maintained the existing regime of property and social hierarchy.”

This pseudo-revolutionary stance makes fascism hard to place on the Left or Right. But it is definitely not in the middle with its hatred for compromise.

The ultimate fascist response to the Right-Left political map was to claim they had made it obsolete by being “neither Right nor Left,” transcending such outdated divisions and uniting the nation.

Fascism is contradictory on modernity

Fascism also contains a contradiction in rhetoric and action when it comes to modernization. Fascists curse soulless and immoral cities and praise rural agrarian utopias. But fascists love fast cars, planes, modern propaganda, and the military strength of modern industry.

This needs to be understood as fascism develops over time.

Early fascists exploited the victims of globalization and modernisation for support, but by using modern propaganda. Meanwhile, the modernist “intellectuals” found fascism’s high-tech “look” combined with a critique of modern society refreshing.

Once in power, the fascist push for war required rapid industrialization, and the agrarian concerns were abandoned.

But it was an alternative modernity that Fascist regimes sought: a technically advanced society in which modernity’s strains and divisions had been smothered by fascism’s powers of integration and control.

Many see fascism’s genocide against the Jewish people as anti-modern, a return to barbarism. But arguably, it is really this “alternative” modernity run amok. The Nazi focus on “racial purity” played on modern impulses of medicine, eugenics, the aesthetics of physical perfection, and scientific rejection of morality. The “old-fashioned” pogroms could not have met the brutal efficiency of the Holocaust.

The complex relationship of fascism and modernity cannot be solved at once. We must first see the whole of fascism in action.

The everyday parts of fascism get overlooked

People focus too much on the high drama of fascism, and omit the everyday complicity of the common people.

Fascist movements could never grow without the help of ordinary people, even conventionally good people. Fascists could never attain power without the acquiescence or even active assent of the traditional elites—heads of state, party leaders, high government officials—many of whom felt a fastidious distaste for the crudities of fascist militants. The excesses of fascism in power also required wide complicity among members of the establishment: magistrates, police officials, army officers, businessmen.

To fully understand fascism, we must understand the banal choices people make in their everyday routine.

For example, with the brutality of Kristallnacht, people were horrified. But the widespread distaste did not last, and no major legal action resulted. If we can understand how people let that happen, we can better understand an event like the Holocaust.

Defining fascism is difficult

Many have looked for a “fascist minimum,” trying to reduce fascism down to a simple “essence” for a definition.

But definitions are inherently limiting. It looks at fascism as frozen, when it’s a process, and focuses more on what fascists said than what they did.

We do need an agreed concept of fascism. But the aim of this book is to arrive to such a definition at the end, not the start, after we have studied regimes generally accepted as fascist in practice, namely Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany.

We start with a strategy rather than a definition.

Strategies of Analysis

Fascism is unlike other “ism”s

People think of fascism as an ideology, in the same manner as liberalism, conservatism, or socialism. Hitler and Mussolini loudly proclaimed they were prophets of a new worldview or idea. A fascist, then, is someone who expresses fascist ideology, and turns this into a fascist project. Therefore to study fascism, we must first study its thinkers and programs, and then see how this unfolds in action.

However, this approach assumes that fascism really is the same as these other ideologies.

Putting programs first rests on the unstated assumption that fascism was an “ism” like the other great political systems of the modern world: conservatism, liberalism, socialism.

This is mistaken. The other ideologies rested on coherent philosophical systems laid out by systematic thinkers. Fascism was not.

Fascism was built on aesthetic, not doctrine

Fascism appealed by ritual, ceremony, and rhetoric. They did not particularly care about the truth or falsity of what they said.

Fascism does not rest explicitly upon an elaborated philosophical system, but rather upon popular feelings about master races, their unjust lot, and their rightful predominance over inferior peoples. It has not been given intellectual underpinnings by any system builder, like Marx, or by any major critical intelligence, like Mill, Burke, or Tocqueville.

In a way utterly unlike the classical “isms,” the rightness of fascism does not depend on the truth of any of the propositions advanced in its name. Fascism is “true” insofar as it helps fulfill the destiny of a chosen race or people or blood, locked with other peoples in a Darwinian struggle, and not in the light of some abstract and universal reason.

The early fascists were open about this. “The truth” was whatever let the fascist people dominate. Fascists think of ideology as a sensual experience and mystic union with their leader. It is “politics as aesthetics,” with the ultimate aesthetic being war.

Fascist leaders bragged about their lack of doctrine

Fascists leaders were open that they had no program. Mussolini even bragged about its absence.

A few months before he became prime minister of Italy, he replied truculently to a critic who demanded to know what his program was: “The democrats of Il Mondo want to know our program? It is to break the bones of the democrats of Il Mondo. And the sooner the better.” “The fist,” asserted a Fascist militant in 1920, “is the synthesis of our theory.” Mussolini liked to declare that he himself was the definition of Fascism. The will and leadership of a Duce was what a modern people needed, not a doctrine. Only in 1932, after he had been in power for ten years, and when he wanted to “normalize” his regime, did Mussolini expound Fascist doctrine, in an article (partly ghostwritten by the philosopher Giovanni Gentile) for the new Enciclopedia italiana. Power came first, then doctrine.

Hitler had a program, which he ignored and mocked those who took it seriously.

It was zeal, not reasoned assent, that mattered.

Hence the reason fascist leaders did not bother to justify changing their program. For comparison, Stalin constantly wrote to show how his policies conformed with the thought of Marx and Lenin. Hitler and Mussolini did not.

Early fascist thinkers are still important though

Fascist intellectuals played a key role at the start of fascism. They created a space for fascists by undermining Enlightenment values, before then widely accepted. They made it possible to “imagine” fascism, which made a fascist revolution culturally possible. They gave an alternative course for the angry who desired change.

Fascist ideology also played a role at the end on the battlefield, with their race hatred and anti-liberal or anti-humanist values reasserted in the killing field.

But fascist ideology plays a weird role in the middle. To gain power, fascist leaders needed to build alliances and compromises, and therefore abandon their ideological program.

We must study the context of fascism

Some approach fascism by seeing the crisis is responded to.

For example, Marxists say fascism was a response to the crisis of capitalism. Capitalism was unable, by normal operation of constitutional regimes and free markets, to guarantee constant access to cheap resources and labor and a widening market.

Others see it as a failure of liberalism to deal with the challenges of a post-1914 world of command economies, mass unemployment, inflation, extending the vote, and social tension, spurred on by wartime propaganda and international debt.

However, fascists primarily hate socialists, not liberals, who are seen as the enablers of socialism by being too weak. When liberals want to fight socialism, they work with fascists to do it.

Fascists hated liberals as much as they hated socialists, but for different reasons. For fascists, the internationalist, socialist Left was the enemy and the liberals were the enemies accomplices. With their handsoff government, their trust in open discussion, their weak hold over mass opinion, and their reluctance to use force, liberals were, in fascist eyes, culpably incompetent guardians of the nation against the class warfare waged by the socialists. As for beleaguered middle-class liberals themselves, fearful of a rising Left, lacking the secret of mass appeal, facing the unpalatable choices offered them by the twentieth century, they have sometimes been as ready as conservatives to cooperate with fascists.

Fascism is essentially diverse between nations

Fascism has no universal value except the success of the “chosen people” in Darwinian dominance. Fascism does not care about “individual rights” or “due process.” It cares about the success of the Volk or the razza.

Fascism finds its expression in its particular culture. Unlike other “Ism”s, it is not for export. There is no fascist internationalism.

Instead of making studying fascism impossible, being unique in every society, we should make this a virtue of our analysis. We will instead look at the different fascist movements and see how and why they went along different paths.

Where Do We Go From Here?

Three strategies of defining fascism

There have been three responses in the search for a fascist minimum.

The first group simply deny that fascism means anything. They claim there is only “Mussolini-ism” or “Hitler-ism” which have both been labeled fascist by historical accident.

Paxton disagrees. The term fascism should be rescued from sloppy usage, not abandoned to it. We need a term for this political innovation of the 20th century of a popular movement against the Left and liberal individualism.

The diversity of fascism is no reason to abandon the term. Communism and liberalism have similar diversity.

Indeed “liberalism” would be an even better candidate for abolition than “fascism,” now that Americans consider “liberals” the far Left while Europeans call “liberals” advocates of a hands-off laissez-faire free market such as Margaret Thatcher, Ronald Reagan, and George W. Bush. Even fascism isn’t as confusing as that.

The second group accepts the variety of fascism, and surveys its various forms. This gives interesting detail, but does not show what unites them.

The third group construct an “ideal type” of fascism that fits no particular case, but is a kind of composite “essence.” This is seen with Roger Griffin’s definition “Fascism is a genus of political ideology whose mythic core in its various permutations is a palingenetic form of populist ultranationalism.”

Paxton rejects these two approaches too, as they make fascism static and isolated.

Fascism and its liberal and conservative collaborators

Instead, we will focus on fascism in action, from its birth to its death, and how it interacts with things along the way. In the process, we will need to understand fascism’s two great collaborators: liberals and conservatives.

Liberals focused on the progressive ideas of a hundred years ago, championing liberty, equality, and fraternity. But they only interpreted these ideas through an educated middle class.

Conservatives wanted the calm order of inherited hierarchies of wealth and birth. They hated mass enthusiasm. The state would be a “night watchman” while the elites rule through property, church, army, and inherited social influence. Conservatives rejected liberty, equality, and fraternity, preferring authority, hierarchy, and deference. They would unite with fascists against the Left, but hated how “uncouth” they were. Still, communism was seen as the bigger threat, so these problems were ignored.

Fascism came to power thanks to frightened ex-liberals, opportunist technocrats, and ex-conservatives.

The Five Stages of Fascism

Following this development over times gives us the stages of fascism, identified by Paxton as this:

The creation of movements

Their rooting in the political system

Their seizure of power

The exercise of power

A long duration tending towards radicalization or entropy

Each later stage requires the earlier, but the earlier stages do not guarantee the later ones. Fascist movements can be stopped or slip backwards.

While most countries had fascist movement, only Nazi Germany went to the limits of radicalization.

Dividing fascism this way also allows us to analyze fascist movements at different stages of development, and understand its choices.