The Third Meditation in Plain Language

In the previous meditation, I demonstrated the certainty of my own existence as “a thinking thing.” I doubt, affirm, and deny. I understand some things, and am ignorant of other things. I can will certain things, and refuse others. I also have sensory perceptions.

I do not, however, have any proof that what I experience actually conforms to reality. It might all be a dream or an illusion. So while I know that I am a “thinking thing” that does what I described above, I do not know, for example, that I have a body.

Why can I say that I know I exist? Apparently because I can recognize it clearly and distinctly. I can establish a new general rule then: Whatever I perceive very clearly and distinctly is true.1

But previously I thought I perceived many things clearly and distinctly which I now find doubtful. The existence of the objects I perceive, for example, like the earth, trees, the stars, and so on. But what I perceived was the sense experience itself, and I do not doubt that at all. Even if the world is a dream, I still am experiencing it.

What about when I considered simple math problems, like that 2+3=5? I perceived that clearly and distinctly too. The only reason for doubting it I could think of was if some God made me so deceived I could get even that wrong. Given how powerful I believed God to be, he could definitely do it if he wanted to.

This objection remains pretty weak though, I have to admit. I haven’t even found any evidence that this God even exists, let alone that he would be a deceiver.

Still, it’d be nice to remove this doubt if I can. If I can’t, it seems like I can’t be certain of anything else.

That’s a big problem to tackle. Let me start by trying to organize my thoughts a bit more into what which are even capable of being true or false.

First I have “ideas.” These are my thoughts which are images or pictures of things, like when I think of a man, a chimera, the sky, an angel, God, etc.

I also have “judgments.” This is when I will something, fear something, or affirm or deny things, and so on. Judgments involve ideas, but also something more than the mere likeness of a thing.

Ideas in themselves cannot be false. If I imagine a thing, it is true that I imagine it. Nor can my will or emotions be false, since, even if I want a bad thing, it is still true that I want it.

Only judgments then can be false. One of the most common mistaken judgments is assuming my ideas resemble the world outside me.

Where do I get my ideas from? It seems that they are either: (1) innate to me, (2) come from outside of me, or (3) are invented by me.

Intuitively, I would say that my understanding of ideas like the concept of “thing,” “truth,” or “thought” are all innate to me.

Other ideas, like the things I sense, seem to come from outside me. If I hear a noise or feel the warmth of a fire, I assume there is something other than myself causes these sensations.

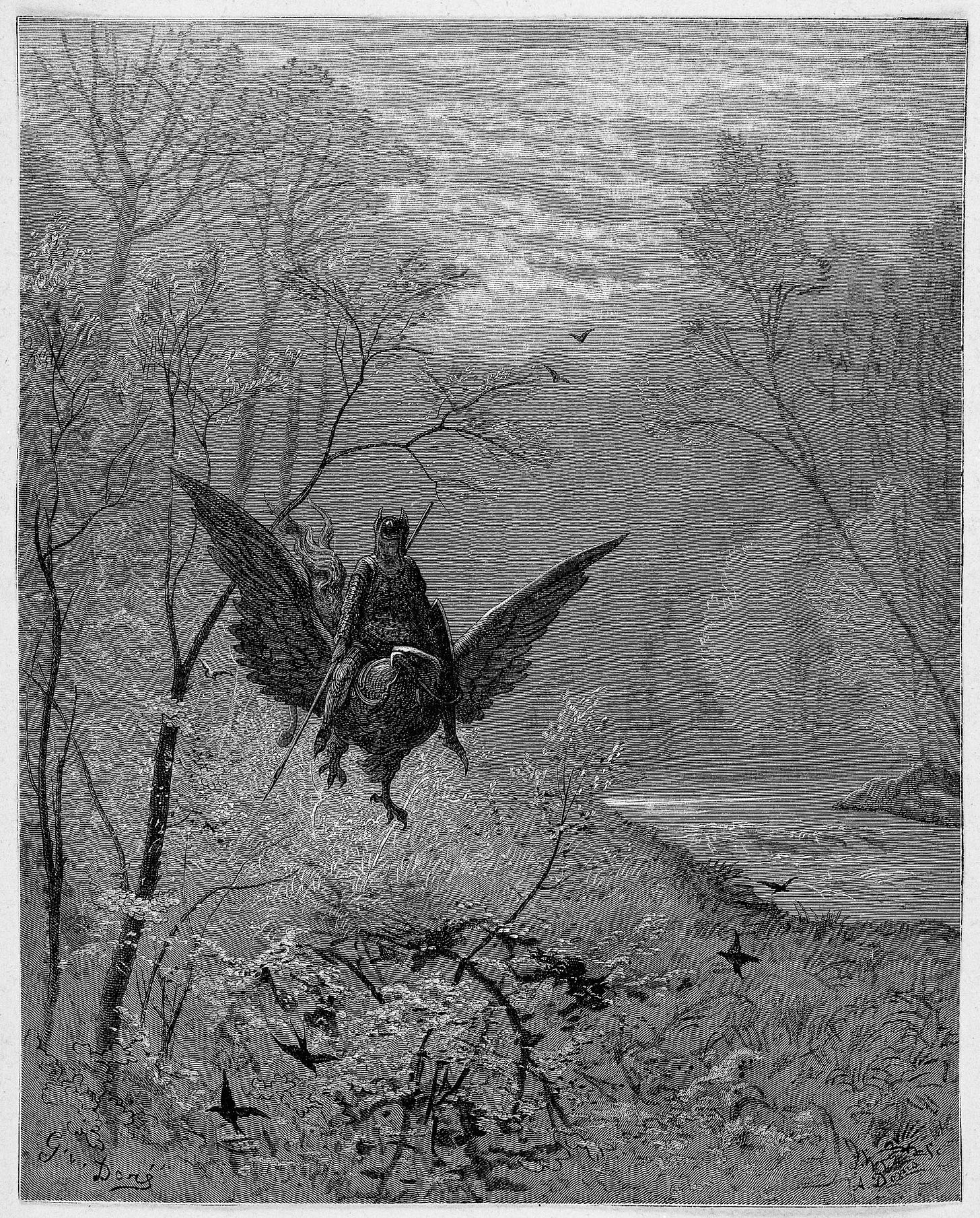

When I imagine something like a hippogriff though, that seems to be an invention. I’m combining other ideas like “eagle” and “horse.”

But these are just my first impressions on how I would categorize these ideas. I don’t actually know what each one is, since I haven’t seen any proof. They might all be coming from outside me or invented.

For now though, I’ll focus on the ideas that seem to come from outside of me. My impression is that, when I sense something, it resembles how things actually are. I suppose these things reflect how the world actually exists.

Why? I can think of three arguments: (1) It seems natural for me to believe this. (2) The things I sense aren’t under the control of my conscious will. If I sit next to a fire, I feel warm regardless of how I wish to feel. (3) Finally, if something is coming to me from the outside, it seems natural to assume that it resembles that outside thing.

Let’s see if these arguments are any good.

First off, what does it mean to say something is “natural” to believe something? Apparently just that I have a spontaneous impulse to accept it.

But that is quite different from things that have been taught to me by the “natural light,” that I have perceived clearly and distinctly, like when I realized that “if I am doubting then I must exist.” That was not itself subject to doubt, whereas something I just feel a random impulse to believe is. In fact, I’m pretty sure my natural impulses have mislead me before, so they absolutely can be doubted.

Secondly, just because something isn’t under the control of my will doesn’t mean it comes from outside of me. Maybe there are parts to me other than my will which can produce ideas without external help. That’s generally how I thought dreaming worked already. Plus, I also just talked about the “natural impulses” I have which even seems opposed to my will, yet still coming from me. This is good evidence that I can cause things that my will does not cause.

Finally, even if I assume these ideas are being caused by external things for the sake of argument, that is no evidence that my ideas resemble those things. How things seem can be quite different from how they are. For example, the sun seems to be very small to our eyes, but using some simple math I can actually astronomical calculations I can determine it is many times greater than the size of the Earth!

It is not reliable judgment then, but blind impulse, that leads us to think the things I sense resemble the things themselves.

Perhaps I can make a more subtle argument here by examining the different kinds of content for my ideas.

As mental events, all of my ideas seem roughly the same. They are all modes of my thought. But what they represent differs wildly.

Some of my ideas represent certain substances, like the sun or a unicorn, while other ideas represent mere modes, accidents, or qualities of substances, like something being the color white or being large. For example, I am a thinking thing, but my thoughts are certain modes of my existence.

I will call the reality something possesses as a representation of something “objective reality” or “representative reality.”2

More than that, when an idea is representing something greater, I may also say it has a greater representative reality compared to other ideas, even if ideas are all equal as ideas.

The idea of a substance therefore has a greater degree of representative reality, a higher perfection, than the idea of a mere quality, which is only a mode or accident of some substance. Likewise, the idea of an infinite substance which creates everything else, namely God, represents something greater than the idea of a mere finite substance.

Another point which I see by the natural light to me is that something cannot give what it does not have. A cause must therefore have at least as much reality as the effect.

Two things follow from this:

Something cannot arise from nothing.

What is more perfect (contains more reality) cannot arise from what is less perfect.

This is all true not only of what I might call “formal,” “intrinsic,” or “actual” reality, namely mind-independent reality, but also of representative reality.

The former is more familiar to us. I know that a stone cannot be created except by something that contains, either directly or in some higher form, everything to be found in a stone. Likewise, I cannot heat something cold except by using something that I cannot heat something that is cold except by using something that has at least the same degree of perfection as heat.

Note that I am not saying here “except by something that is itself hot,” because that’s not true. Something could not be itself hot, yet still cause heat in something else if it has a greater degree of perfection. This is what I said that God or the evil demon might be able to do earlier.

But the same is true for ideas. The idea of a stone or heat cannot be created in me except by something with an equal degree of reality. An idea therefore does not need any formal reality except what it derives from me as a thinking thing, but anything that has representative reality must come from something that has an equal or greater level of formal reality. The idea cannot contain something that was not in its causes. Something cannot come from nothing.

Maybe I can object to this that something need not have formal reality to cause ideas, but only representative reality. But this is just saying that one idea can cause another, since only ideas have representative reality. This certainly does happen, but it isn’t a sufficient explanation here because, tracing these ideas back far enough, I ultimately come to some archetypical idea which was not caused by any other idea. There can be no infinite regress of ideas. But in that case, this idea must be getting its representative reality by something which has it actually as part of its formal reality.

The natural light therefore teaches me that ideas may fall short of the perfection of their causes, but they can never surpass them.

It follows from all this that if I can find in my mind some idea that has a greater representative reality than I formally possess, then I know that I am not the cause of this idea, and I will know that something else is.

However, if I can find no such idea, it also follows that I will have no proof that I am not alone in the world. This is the only way out of this problem that I’ve been able to think of.

I can now examine my ideas to see if this strategy has any hope. Besides my idea of myself, I have ideas of many different things, including God, inanimate bodies, angels, animals, and other people like me.

For angels, animals, and other people, I can see that I could have easily invented these by combining my other ideas of God, inanimate bodies, and myself. I will discount everything in these categories then.

As for bodies, nothing about them seems so special about them that I couldn’t have invented that either. As far as I can tell, especially as informed by my previous wax example, here is a complete list of everything I can perceive clearly and distinctly in them:

Size (which is just extension in length, breadth, and depth)

Shape (which is the boundary of the extension)

Position (which is a relation between it and other objects with shape)

Motion (which is just change in position)

On this list I can also add some other basic categories like substance, duration, and number.

Everything else that I sense like color, sound, smell, and so on, I have a harder time of saying what they are. For example, I cannot intuitively tell whether heat is the absence of cold, or cold is the absence of heat. Maybe both? Or neither? If an absence is presenting itself to me as a real thing though, I think I could judge that ‘false’ in some sense.

If they are false non-realities, then it only seems to me like they exist because of some defect on my part. If they are real, they seem to be something minor since I can’t even tell.

Of the remaining things I can see clearly and distinctly in bodies, namely their substance, duration, and number, these are all things that I have too. Granted there are some differences. I am a thinking thing and I’m supposing myself to have no extension, whereas I suppose that a stone is an extended thing that doesn’t think. Still, I have the attribute of “substance” in common.

Likewise, I seem to exist in time. I can remember moments from before now. I also have numerous thoughts which I can count. I can get the ideas of duration and number from myself then, and do not need to appeal to anything else.

For the other elements like extension, I am not supposing I am myself extended. All I am saying about myself is that I am a thinking thing. But as these are mere modes of existence for a substance, it is possible that I am the source of these things too, since I have the greater perfection as a substance.

By process of elimination then, I am left with one remaining idea: God.

By the word “God” I understand an infinite, eternal, unchanging, independent, supremely intelligent, supremely powerful substance that created me and everything else that exists.

The more I consider these attributes, the less they seem like the could have come from me. It would, therefore, come from God, the infinite substance himself.

But maybe not. Perhaps I arrive at this idea of infinity by negating the finite, like how my idea of rest negates the idea of movement.

This would be wrong for a few reasons.

First of all, there is obviously more reality in the infinite than the finite, which means that the perception of the infinite is prior to the finite, rather than the other way around. I grasp my own limits by comparing it to something unlimited.

Nor could the idea of God be something “materially false,” like I suggested about heat and cold before, to allow it to come from nothing. They were so unclear that they might be confused for nothing at all, whereas my idea of God is as something with more representative reality than any other idea.

Even if I suppose that God does not exist, I cannot suppose that the idea of God represents an absence in the way that darkness is the absence of light.

The idea is clear and distinct to me, even though I cannot fully grasp the infinite. There are certainly far more attributes of God that I am incapable of understanding, simply by the very fact that an infinite being surpasses my finite mind.

It is enough that I understand the infinite, and work with the attributes that I do grasp. I know all the attributes I clearly and distinctly perceive implies a kind of perfection, a kind of reality. God, as the creator of all other things, either has these perfections in a straightforward way or in a higher form.

Let me push back against this with another objection. Maybe all the perfections that I attribute to God really are ones that I have potentially instead of actually. For example, since I started this meditation, my knowledge has increased, and I can see no obvious reason why this might not go on to infinity. Perhaps this potential is the source of my idea of this infinite perfection, meaning the idea really does arise from myself instead of something other than me.

But this is wrong for three reasons.

Firstly, while it is true I have certain unfulfilled potentials, this is irrelevant for my idea of God who is pure actuality, having no potential.

Secondly, even if my knowledge did increase forever, it will never actually be infinite. I can always add more. This is unlike God, who is actually infinite, so nothing can be added to him.

Thirdly, strictly speaking, potential being is nothing. Only an actual being, something really real, can act as a cause of the representative reality of my ideas.

All of this is true enough, but a bit complex. If I let my attention wander, it can be hard to keep the whole argument in mind at once.

Maybe I can approach the question another way: If God, the perfect being, did not exist, could I exist?

If God did not exist, where would I get my existence from? I can think of three answers: (1) from myself, (2) from my parents, or (3) from some being less perfect than God (since nothing can be more perfect, or even equally perfect).

I can rule out getting existence from myself. If I could do that, I would just be God, and could give myself all perfections I can think of.

Alternatively, suppose I just have always existed in this imperfect state. Would it follow then that I do not need a cause? No, because even if I exist at one moment, that does not guarantee that I will exist in the next. I therefore need some other cause to keep me in existence, sustaining me in reality. Whatever is needed to create something is also needed to keep it in existence. There is only a conceptual distinction between creating and preserving then.

I know I exist now. Can I make it so that I exist a minute from now? I have no awareness of such a power, and as I am considering myself only as a thinking thing, that gives me a pretty clear “no.” My existence depends on something else.

But it might depend on something other than God, like my parents. But that isn’t a satisfactory answer either. The cause must have at least as much reality as the effect. The cause of me then must itself a thinking thing, or contain this in some higher form, and also be able to cause the idea of God within me.

If my cause is self-causing, able to exist on its own strength, then it is God and provides itself with all perfections. If my cause is something less, then it must be getting its existence from something else as well. This just pushes back the problem until we arrive to God, even if we go through however many intermediaries.

This series cannot run back to infinity, especially since I am dealing not only with something that created me in the past (like my parents), but something that preserves me moment to moment.

What if my idea of God does not have a single cause though? Maybe I get the idea of a perfection from one thing, and another from another, combining them all into this notion of “God”?

This cannot be right either because of divine simplicity. God is not a complex thing made up of many parts, as he would be if I were just combining these perfections together in my mind. The perfections are united together in the single divine substance.

Finally, with regard to my parents, even if everything I believed about them were true, they would have brought me into existence without keeping me in existence. But as a thinking thing apparently separated from matter, it seems doubtful that they even made me at all.

Since nothing else can be the cause of me and my idea of a perfect being, God is the only option left. Therefore the fact that I exist, and have this idea of God within me, proves that God really exists too.

How did I get this idea of God? It did not come to me through my senses. Nor is it something I invented, since nothing can be taken away from or added to it. The idea of God is therefore innate within me, just like my idea of myself.

God, as my creator, placed this idea within me. It is not surprising that a craftsman would mark their creation with the seal of their work. By examining myself, I have some notion of the divine then. In all the ways I am lacking, I know exist in God as a perfection in the highest degree. No defect exists in God at all.

This also makes it clear that God cannot be a deceiver, since all fraud and deception depends on some defect.

That claim needs to be examined more closely next time. For now, I can pause here and contemplate the majesty of God a bit more. As a thinking thing, contemplating the best thing brings me the greatest joy I can have.

Comments on the Third Meditation

The Third Meditation in Descartes’ Thought

The first two meditations of this work are by far the more famous, with Descartes’ “evil demon” example especially presenting a serious challenge to our certainty about the world around us, and the “cogito ergo sum” argument establishing at least the certainty of solipsism. His argument is easily grasped by someone even without formal philosophical training, and it can inspire all kinds of sci-fi premises like with The Matrix.

By comparison, Descartes’ thoughts on God are more frequently downplayed. For some, it is even presented as something he tacked on to avoid religious persecution, which was not an unwarranted fear in the time Galileo. For example, Peter Kropotkin wrote in his Ethics: Origin and Development (1922):

Descartes carefully avoided all attacks upon the teachings of the Church; he even advanced a series of proofs of the existence of God. These proofs, however, are based on such abstract reasoning that they produced the impression of being inserted only for the purpose of avoiding the accusation of atheism. But the scientific part of Descartes’s teaching was so constructed that it contained no evidence of the interference of the Creator’s will. Descartes’s God, like Spinoza’s God in later times, was the great Universe as a whole, Nature itself. When he wrote of the psychic life of man he endeavoured to give it a physiological interpretation despite the limited knowledge then available in the field of physiology.

I won’t comment on what Descartes did to avoid persecution here, but I would say that abstract arguments for God are nothing new (the ontological argument, for instance, had been developed centuries earlier). As this chapter makes clear, it also doesn’t seem like God has been ‘tacked on’ to the rest of his philosophical argument here. Rather, our certainty of God’s existence is meant to be the first step to establishing our certainty in the existence of things besides ourselves. Nor does Descartes’ notion of God seem particularly pantheistic here in the style of Spinoza, even if Spinoza was obviously inspired by Descartes. I maintain then that his argument deserves serious consideration as a central part of his project.

Descartes has set an extremely high bar for what can qualify as knowledge, so any argument he gives for God would need that same kind of certainty. Descartes at least believed he had reached that certainty with this argument. Mixed in with this though is some very interesting analysis of our categories of thought as Descartes continues to examine his own mind.

Categories of Ideas

After the second Meditation, Descartes has established that his own existence is certain, although he still doubts many things about himself. His argument that “I think, therefore I am” doesn’t establish much about himself except that he is a “thinking thing.” He does not know then, for example, that he has a body, or have any reason to trust his memory. He knows that he exist, but still not that he is being deceived by the evil demon in every other respect.

Because of this, his focus shifts to whether he can establish, with absolute certainty, the existence of anything beside himself. Just like he trusts in his own existence, he declares that anything else he sees “clearly and distinctly” must be true too.

With this in mind, he begins to examine himself further as a “thinking thing” and categorize his thoughts between things like “ideas” or “judgments.”

Since he is focused here with establishing the existence of something aside from himself, he asks himself whether he can prove where his ideas come from. He believes there are three possible answers. In the first place, they might be ‘innate’ to himself, not needing to appeal to any kind of external source (e.g. his idea of ‘truth’). Secondly, they might come from something other than himself and external to him (e.g. things he can see with his eyes). Finally, he might combine these two things as an ‘invention,’ taking an idea from the outside and reworking it into something new (e.g. something he imagines like a mermaid).

The possibility of ‘innate’ ideas would become especially controversial later on. Empiricists like John Locke would argue that there is no such thing as innate ideas, saying all concepts are derived from experience. But we aren’t concerned with that here.

Degrees and Kinds of Reality

Descartes seems to have no way of proving whether an idea is external to him or not. For example, if it turns out that life is all a dream, then it seems like everything we believed was “external” to us was really part of us all along. Or even if it does come from the outside, we have no way of showing the real world resembles what we see, as in the case of the evil demon.

Because of this, he decides to take a bit of a trickier approach.

His ideas are all equal to one another as ideas, but they are unequal in terms of what they represent. By this he does not just mean that they represent different things, but that they can also represent things that are categorically greater or lesser than other things. He calls this an idea’s level of “objective reality,” although it is perhaps better understood as its “representative reality.”

Descartes argument here takes a bit of a stranger turn. While previously his argument before was rather straightforward, he doesn’t elaborate enough here to explain what he means by this. From context it seems to mean that something has a greater level of ‘representative reality’ to the degree which it is independent. So a quality or a mode, like being the color blue, is a lesser reality than a substance because it depends on some substance to exist. For the color blue to exist, there must be some thing, some substance, that is in fact blue.

It is also important to note that an idea having ‘representative reality’ doesn’t mean that the thing it represents is actually real. Or at least it usually doesn’t. Mermaids might not actually exist, for example, but our idea of them does. The very nature of a mermaid they still have a higher degree of ‘representative reality’ than a quality.

For Descartes, most of this was rather intuitive, so he kind of glazes over this point, which is unfortunate for an argument claiming such a high degree of certainty as to be literally beyond doubt. Maybe it would be if we could ‘clearly and distinctly’ see what he means, but many people cannot, even in his own day. It actually seems more intuitive to people to say that there are not degrees of reality. For example, the English philosopher Thomas Hobbes sent many objections and challenges to Descartes, and this was one of the points he pushed him on. He wrote to Descartes:

Moreover, would M. Descartes please give some thought once again to what he means by “more reality”? Does reality admit of degrees? Or, if he thinks that one thing is greater than another, would he please give some thought to how this could be explained to our understanding with the same level of astuteness required in all demonstrations, and such as he himself has used on other occasions.

We are lucky enough to have Descartes’ reply to this too, but it is underwhelming.

I have sufficiently explained how reality admits of degrees: namely, in precisely the way that a substance is a thing to a greater degree than is a mode. And if there are real qualities or incomplete substances, these are things to a greater degree than are modes, but to a lesser extent than are complete substances. And finally, if there is an infinite and independent substance, it is a thing to a greater degree than is a finite and dependent substance. But all of this is utterly self-evident.

Simply saying something is ‘self-evident’ hardly seems like a sufficient explanation.

If we are to interpret Descartes charitably here though, I think understanding this in terms of dependency is probably the best approach. Something has ‘more reality’ to the extent it does not depend on other things to make it real.

Perfection

For Descartes, to have more reality also makes something more perfect. There is a kind of equivalency being made here between reality and being which has a longer philosophical tradition. This is because to be ‘perfect’ is taken the same way as being ‘complete,’ lacking in no part, or having no defect. This is not just a sense of moral perfection (although it is that too), but also the sense of a “perfect circle.”

This can be found in Aristotle’s Metaphysics, Book V:

"Perfect" <or "complete"> means:

(a) That outside which it is impossible to find even a single one of its parts; e.g., the complete time of each thing is that outside which it is impossible to find any time which is a part of it.

(b) That which, in respect of goodness or excellence, cannot be surpassed in its kind; e.g., a doctor and a musician are "perfect" when they have no deficiency in respect of the form of their peculiar excellence. And thus by an extension of the meaning we use the term in a bad connection, and speak of a "perfect" humbug and a "perfect" thief; since indeed we call them "good"— e.g. a "good" thief and a "good" humbug.

(c) And goodness is a kind of perfection. For each thing, and every substance, is perfect when, and only when, in respect of the form of its peculiar excellence, it lacks no particle of its natural magnitude.

(d) Things which have attained their end, if their end is good, are called "perfect"; for they are perfect in virtue of having attained the end. […]

Things, then, which are called "perfect" in themselves are so called in all these senses; either because in respect of excellence they have no deficiency and cannot be surpassed, and because no part of them can be found outside them; or because, in general, they are unsurpassed in each particular class, and have no part outside.

This was picked up by later scholastic philosophers. For example, the theologian Thomas Aquinas argued in his Summa Theologica (I:Q4:A1) that, because God was “pure actuality,” then it also necessarily followed that God was perfect:

Now God is the first principle, not material, but in the order of efficient cause, which must be most perfect. For just as matter, as such, is merely potential, an agent, as such, is in the state of actuality. Hence, the first active principle must needs be most actual, and therefore most perfect; for a thing is perfect in proportion to its state of actuality, because we call that perfect which lacks nothing of the mode of its perfection.

Given that this language more standard at the time Descartes was writing, his argument might seem less strange. He had a different audience in mind, and divorced from that context some of his argument might seem less straightforward to us. This is not to say that there are no leaps of logic being made here, but that if there are, they are more subtle than we may assume.

Causal Adequacy

Descartes’ next claim is easier to grasp: something cannot give what it does not have. The total cause of something must therefore contain at least as much reality as the effect, either directly or in a higher form. He asserts that he sees this clearly and distinctly, and so long as we accept his idea of containing “more reality” it is hard to dispute.

That to give something we need to have it seems like a logical truism. But this is also applied here to the “levels of reality” theory, so that a quality may produce another quality, but it cannot produce a substance. A substance on the other hand may cause another substance or a quality. In fact, it seems like all qualities must be caused by substances, precisely because they are dependent on them.

Descartes therefore deduces two conclusions from this:

Something cannot arise from nothing.

What is more perfect (contains more reality) cannot arise from what is less perfect.

Both of these seem to flow in straightforward ways. If something cannot give what it does not have, then ‘nothing’ has nothing to give. Likewise, if we have an actual thing, it must ‘contain’ what is gives. This is sometimes called the “causal adequacy principle.”

The ‘contain’ part allows a decent bit of flexibility. We might think of some examples that might seem to contradict this if we didn’t interpret this properly. For example, in an exothermic reaction, chemicals that might not be hot by themselves will release heat when combined. But they nevertheless ‘contained’ heat, as this energy isn’t coming from nowhere.

Descartes’ seems to have more extreme examples in mind, like how he supposes God is immaterial, yet the cause of all things, including hot things. God is able to do this because, as infinite substance containing all perfections, there is nothing that can or does exist that he would not have in its highest form. But we can perhaps more easily accept this with the connection between qualities and substances.

An important way this plays out though is in how representative reality is created in our ideas. Descartes argues that whatever originally produces these ideas in our mind must actually have that thing to give. There is a kind of correspondence therefore between representative reality and formal reality. A quality could not produce the idea of a substance since it does not contain the perfection of ‘substance’ within it. That could only be done by another substance.

This is key to Descartes’ argument from here on. He has established the certainty of his own existence, and he knows his ideas have a kind of ‘representative reality’ within them. He also has a criterion for what kind of thing could or could not cause these ideas within him. This gives him the opportunity to prove the existence of something besides himself if he can find some idea within him that could not have been produced by himself, since that would require the existence of some other formally real thing.

Candidates for Other Real Things

This is all obviously working towards “God” as the answer, as the structure of this hierarchy of being makes clear. We have been given three options in this hierarchy of qualities/modes, finite substances like Descartes himself, and the infinite substance of God. But his buildup to that conclusion is worth considering too.

To see if he has any ideas that he could not have produced, he first gives what seems like an incomplete list of the different kinds of things, besides himself, that he has an idea of: God, inanimate bodies, angels, animals, and other people like himself.

Why this list? I suspect the reasoning was that, with his dualistic framework, he’s breaking down different parts of reality down this way:

Non-ensouled matter (inanimate bodies, maybe also plants)

Ensouled matter (animals, plants?)

Ensouled matter with a non-physical mind like himself (humans)

Purely spiritual minds (angels)

God

To narrow down this list, he tries to simplify this to ideas which could be derived from the others. He is certain of his own existence, so he rules out other people as something he couldn’t invent. He has an idea of God and of himself as something with a mind, so he eliminates angels as something he could have invented as an in-between thing. He also has this idea of inanimate objects, so he eliminates animals as another kind of in-between state. This leaves our actual list of candidates like this:

Physical bodies

God

Descartes’ Notion of Material Bodies

He does not see in the idea of physical bodies anything so special that he categorically could not have invented it. Following his wax example, he thinks the entire idea can be reduced down to a few simple geometric categories (i.e. size, shape, position, and motion), as well as other features that he shares with it (substance, duration, and number).

The features he shares doesn’t help him in proving the existence of anything other than himself. But other aspects like what he senses about them (i.e. their color, sound, smell, temperature etc.) are a bit more strange, but it’s precisely that strangeness that keeps him from making any kind of definitive argument that it’d be impossible for him to create. At times he seems to be unclear whether these things are even “things” at all, or a mere absence, like how cold is really just the absence of heat.

Keep in mind that, to prove that other things exist, he needs to be able to prove that these ideas don’t come from him. If he cannot do that, he doubts it. So while it seems natural to me that someone blind from birth can have no idea of the color ‘red,’ I’m not sure I could prove that to the kind of standard Descartes has set. I don’t see a way to prove it is not coming from some secret part of myself that I am unconscious of.

The Trademark Argument for God

The real meat of the argument is what comes after, regarding God.

God here should be understood more in the western philosophical tradition, especially as understood within scholasticism, in contrast to, say, the way gods are presented in the Bible. Descartes, as a Roman Catholic, would ultimately equate the trinitarian God of Christianity, but as he is working from a place of extreme skepticism here he instead focuses on this more philosophical definition.

He therefore defines God as “an infinite, eternal, unchanging, independent, supremely intelligent, supremely powerful substance that created me and everything else that exists.” Nothing here would be unfamiliar to the medieval theologian.

The idea of God immediately strikes as unlike Descartes’ other ideas, precisely because it is representing “infinite substance,” a maximal degree of reality or perfection.

According to his earlier reasoning though, the representative reality of an idea can only be created by something with an equal or greater amount of formal reality. God, as maximally real, obviously has nothing greater than him. It follows that only a God (or the God, since Descartes argues his conception implies there can be only one) could create the idea of God within us.

This argument is sometimes confused with ontological argument for God’s existence, which Descartes also argues for later in his fifth meditation, but it is distinct. The ontological argument argues that, by the very definition of God. The trademark argument on the other hand is based on the idea of God being only something God himself could have created. This can be a subtle distinction, but an important one.

Objections to the Trademark Argument

If we are going to push back against this idea, unless we attack one of the premises that led up to this point, is to either argue against us having any such idea of God in the first place, or to argue we can arrive to that idea through other means.

Descartes presents two ways he might arrive at the idea of God from himself: from his finitude or from his potential.

The former strikes me as the more obvious method. By seeing ourselves as a finite being, we abstract away the ways in which we are finite to arrive at the idea of an infinite being. For example, Descartes knows that he is someone with limited knowledge, even if it is increasing. Can’t he use this to invent the idea of an omniscient God, with no such limits on his knowledge?

Descartes argues that we cannot do this though, precisely because it gets things backwards. We don’t get our idea of infinity from the finite, but rather are able to recognize things as finite by comparing them to infinity. This also is consistent with the principle of causal adequacy, since infinity contains more “reality” than finite beings, meaning the finite could never produce the idea of infinity.

Descartes argues that appeals to his potential are similarly flawed. He can recognize the ways he is finite, especially as he considers the limits of his own knowledge. But maybe he has the potential to become God himself, to learn an infinite amount. Could he have invented the idea of God using this potential?

Again, the answer seems to be no. Potentiality plays a big part in Aristotelian/Scholastic metaphysics. It is not strictly nothing, since your potential for something is real, but it hasn’t been actualized. My lottery ticket may potentially win me $100 million, but unless that potential is realized it doesn’t do me any good. Likewise, only something actual can work as a cause, and if we try to turn this into looking back at my own actual existence as a limited finite thing, this reduces back to the previous objection.

To this, I think one more point should be made: Don’t we learn about the idea of God from other people? We don’t seem to be born with this knowledge, but are taught about God by our parents, church, school, television, or whatever else. People have also conceived of God (or the gods) in very different ways, and not necessarily as this maximally perfect being Descartes has in mind. In the Abrahamic tradition, Adonai was a storm deity, and only gained his level of prominence after campaigns of conflation with the god El, and even then was only a god among gods. The kind of monotheistic view Descartes has in mind was a much later development. Doesn’t this prove that our idea of God is not innately implanted in us by God?

Perhaps not. We might have certain innate ideas in us that we, nevertheless, have not had called to our attention yet. Someone may not know the Pythagorean theorem, for example, but any right triangle they imagine would still conform to it. The example from Plato’s Meno helping a slave ‘remember’ geometry comes to mind. Even if we are taught about God then, this teaching may only be effective because it’s pointing out something that is already an element of our thought.

The Preservation Argument for God

Given the complexity of the trademark argument, Descartes moves on to what he sees as a more straightforward argument for God’s existence. It is also a causal argument, trying to prove God’s existence by finding something that exists which only God could be the explanation of. But rather than trying to explain the origin of his idea of God, he now tries to explain the source his own existence.

He provides three alternative explanations for our existence other than God: (1) He is self-existent, (2) his existence comes from his parents, or (3) his existence comes something less perfect than God.

Now all of these explanations really reduce to the third, since we have already determined that we are less perfect than God, and the same thing should be true of our parents. It’s basically just saying “literally anything else.” But each is worth some consideration as the first kind of explanations someone might reach for.

Our parents are probably the easiest explanation to rule out. When Descartes is wondering what is causing his existence, he means what is causing him to exist right now. Just because I exist at one moment in time does not guarantee I will exist in the next.

To draw an analogy, a statue is shaped by a sculptor, but it can continue to exist even if the sculptor dies. But if you smash the clay that makes up the statue, it will cease to exist. Likewise, my parents may be an explanation for the origin of my physical body (Descartes doubts this can explain his mind though), but there clearly isn’t the kind of causal dependency we’re talking about here. The death of a parent does not immediately cause the death of their children. We are not dealing with creation in the sense of rearranging preexisting material then, but what is causing there to be material at all instead of nothing.

Descartes’ other options are that he is either he is able to preserve his own existence moment to moment, or he is ultimately preserved by something else which is self-preserving (the language of self-causing is a little strange), but less than God. For example, if we were to find out that our mind, our status as a ‘thinking thing,’ were really just a product of the brain, we’d still have a question about what preserves the brain in existence, or what preserves the matter that makes up the brain. The real question then becomes “Can anything be self-preserving except God?”

Descartes argues the answer as no because, if he could cause his own existence (or perhaps better put as being self-explanatory than self-causing), then he would also be able to give himself every perfection, which would just make himself God. The same would be true for anything else that preserves him too.

The reasoning here is a little harder to follow. We established before that a cause cannot give what it does not have. But why would the ability to cause Descartes also imply the ability to cause every other perfection? Maybe the reasoning is that, if something can be created from nothing, than anything can be created. If I am able to cause my own existence, then I could cause myself to be anything, so why not give myself every perfection? Or maybe the reasoning is that the act of creating a substance, rather than merely modifying it or giving it an attribute, is an act so much greater that any sufficient cause for the former must also be able to do the latter.

Divine Simplicity

Descartes considers another objection to God’s existence, namely that these absolute perfections (e.g. infinite goodness, infinite knowledge, infinite power, etc.) all exist in separate things. Having derived these ideas from different sources, they are then being combined into the singular idea of “God” as if one thing had them all, just like how we might add the idea of a fish tail onto the human to produce the idea of a mermaid.

Descartes dismisses this objection because part of his idea of God is the doctrine of divine simplicity. In my experience, this is an idea of God that even most theists seem to be unaware of. I certainly never heard about it in Sunday school as a kid, probably because it is rather abstract. The idea is that, when we say God is one, we do not merely mean that there is one God, but that everything about God is absolutely unified so that he is not made up of different parts.

In this way, God’s different perfections aren’t actually distinct from one another. God is not just a bundle of these perfections. Rather, the different perfections fundamentally united, not really being different at all, and may only appear different because we are framing this unity in different contexts.

For example, Moses Maimoides wrote in his A Guide for the Perplexed:

There cannot be any belief in the unity of God except by admitting that He is one simple substance, without any composition or plurality of elements; one from whatever side you view it, and by whatever test you examine it; not divisible into two parts in any way and by any cause, nor capable of any form of plurality either objectively or subjectively…

Likewise, Thomas Aquinas wrote in his Summa Theologica (I:Q3:A7):

The absolute simplicity of God may be shown in many ways.

[…]

Thirdly, because every composite has a cause, for things in themselves different cannot unite unless something causes them to unite. But God is uncaused, as shown above (I:2:3), since He is the first efficient cause.

Fourthly, because in every composite there must be potentiality and actuality; but this does not apply to God; for either one of the parts actuates another, or at least all the parts are potential to the whole.

Because of this, Descartes argues that his idea of God cannot be secretly complex, precisely because if we are thinking of anything that is complex, then we are simply not thinking of God at all.

But perhaps this opens Descartes up to another objection: Can we properly think of God at all? If we cannot properly comprehend how all these different features of God (i.e. infinite, eternal, unchangeable, independent, supremely intelligent, supremely powerful, etc.) as really being united, as not really being different features at all, then perhaps we cannot think of God and this point falls apart.

To this, Descartes has agreed that our finite minds can only touch upon the infinite. But despite this, we can still talk about and think about the infinite in some sense. I am using the word ‘infinite’ and have some idea of its meaning in mind. Perhaps we cannot grasp the whole of it, but the limited sense in which we can talk about the infinite is enough for the argument to flow.

Convinced that this idea of God is sufficient, and that our idea of God could only come from God himself, then our having the idea is definitive proof that God exists. Descartes also believes that through this, he has also concluded that the perfectly good God could not be a deceiver. This becomes an important basis for the rest of his philosophy for grounding our certainty in other things besides our knowledge of our own existence and of God’s existence.

When Descartes describes something he understands this way, he often describes it as seeing it by “natural light.”

I have departed a bit from Descartes’ explanation in the text to elaborate on this a bit. Descartes is using the term “objective” in its scholastic sense, which is often almost the exact opposite of its modern sense. When we think of something being objective, we think of it as being “mind-independent,” being a matter of fact outside of a single person’s thoughts or beliefs. Here objective is used more in relation to something being an “object of thought.” Hence the reason it is equated here with “representative reality,” as I’ve seen in one translation. To say something has “objective reality” then is to say it exists as an idea. So while a unicorn may not exist, the idea of a unicorn would have objective reality. When referring to something that exists more in the modern sense of “objective,” Descartes uses the terms formal, actual, or intrinsic reality. A unicorn may therefore have objective reality as an idea, but lack any kind of formal reality if this idea is not actually occurring. Ideas are something of a special case here too, since ideas exist while also representing things, therefore having both formal and objective reality. For more, I highly recommend reading the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy article on Descartes’ Theory of Ideas.