What’s Wrong with the Calendar?

The default calendar of today is the Gregorian calendar. It was introduced in 1582 to replace the Julian calendar, but took centuries to gain real dominance in the world. The British Empire, for example, only adopted it in 1750. We also refer to the Russian Revolution as the ‘October Revolution,’ despite the fact that the Gregorian calendar tells us it took place in early November, because Russia had still been using the Julian calendar up to this point.

Optimally, a unit of time should be consistent and divisible with the other units of time it uses. For example, 60 seconds go into a minute, 60 minutes go into an hour, and 24 hours go into a day. However, we hit an issue when we ask how many days go into the month. Depending on which month and which year we are in, they take either 28, 29, 30, or 31 days long. If I say on May 31st that “I will meet you in a month,” do I mean June 28th, 29th, 30th, or July 1st?

This problem exists for a good reason. A ‘month’ as a unit of time is based around the moon, which takes approximately 29.5 days to cycle through all of its phases. It is literally a ‘moon-th’. However, we base the years, not around the moon, but around the Earth’s revolution around the Sun, specifically as it is being measured as a tropical solar year.

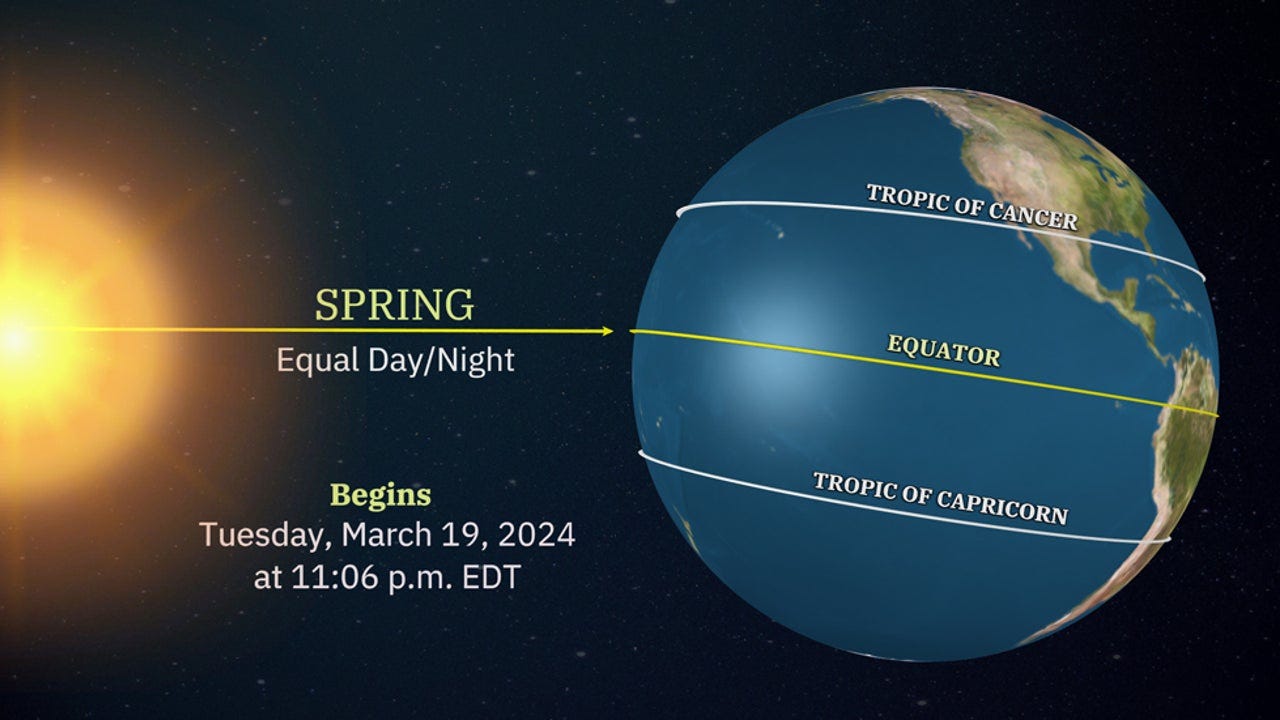

In other words, we determine that the Earth has made a complete revolution around the Sun when it reaches the same point in the sky, namely by using the Summer and Winter solstices or the Spring and Autumnal Equinoxes. On average, the tropical year lasts 365 days, 5 hours, 48 minutes, and 45 seconds. If any calendar year is going to maintain any rough consistency with the tropical solar year, it will need to be inconsistent with itself in some ways. This is why we have things like leap years, correcting for the ‘drift’ the accumulates over the years.

As each moon cycle takes almost 30 days, a month is also generally taken to be roughly 30 days long. However, as we all know, months in the Gregorian calendar are extremely inconsistent, taking either 28, 29, 30, or 31 days.

This is done because 365 is not evenly divisible by 30. The divisors of 365 are 1, 5, 73, and 365. In other words we could have five 73-day “months,” or we could have seventy-three 5-day months, or we could have nothing at all. Dividing the year up any other way, we will not have a perfect match, and some days will be left as a remainder.

If we attempt to divide the 365 days up by 30, we get 12 months with 5 days left-over, and 6 days left-over on the occasional leap year. We must therefore either incorporate these 5 or 6 extra days into the months themselves, as in the Gregorian calendar, or we need some days to be left outside of any month. There can be twelve 30-day months, followed by 5 or 6 days which are not part of any month whatsoever. Neither solution is optimal, but is a matter of physical necessity when we are basing measurements of time off both the Moon and the Sun’s relationships with the Earth.

The Gregorian calendar however, following the Julian calendar, didn’t merely turn five months into 31-days long though. It takes away two days from February to make seven months 31-days long. This was unnecessary. There is no reason why we couldn’t have, say an alternating pattern, giving all odd-numbered months 30 days and all even-numbered months 31 days (except for February which would only have 31 on leap years).

The Gregorian calendar has even more issues than this, but before we consider that, let’s examine what an alternative calendar might look like.

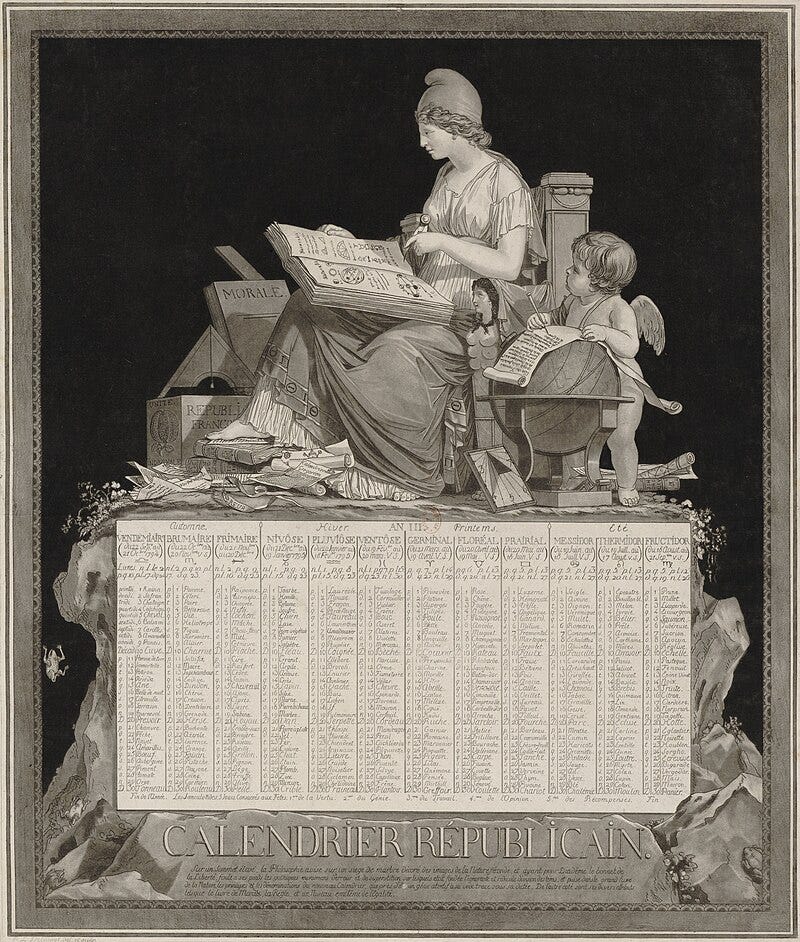

The French Republican Calendar

As a libertarian communist, I have set myself against Jacobinism. In fact, I agree with Daniel Guerin that a major failure of Marxism was its inability to free itself from its influences. But a major point of agreement I share with them is this deep and burning desire to remake the calendar.

The French Republican calendar supported by the Jacobins is probably one of the most famous, and infamous, examples though. Unlike the Gregorian calendar, the Jacobins of the French Revolution wanted to bring about a brand-new system. The beginning of the year was set to the Autumnal Equinox, and the year was divided into twelve 30-day months. Because of this, each month roughly lined up with the four seasons of autumn, winter, spring, and summer. These months were also given entirely new names.

Autumn

Vendémiaire (from ‘vendange’ meaning ‘grape harvest’)

Brumaire (from ‘brume’ meaning ‘mist’)

Frimaire (from ‘frimas’ meaning ‘frost’)

Winter

Nivôse (from ‘nivosus’ meaning ‘snowy’)

Pluviôse (from ‘pluvieux’ meaning ‘rainy’)

Ventôse (from ‘venteux’ meaning ‘windy’)

Spring

Germinal (from ‘germination’)

Floréal (from ‘fleur’ meaning ‘flower’)

Prairial (from ‘prairie’ meaning ‘meadow’)

Summer

Messidor (from ‘messis’ meaning ‘harvest’)

Thermidor (from the Greek ‘thermē’ meaning ‘heat’)

Fructidor (from ‘fructus’ meaning ‘fruit’)

As each month is an equal length of 30 days, 5 days are left-over which are not part of any month (6 days on leap years). These were known as les sans-culottides, designated as their own holidays, and named as follows:

fête de la vertu — Celebration of Virtue

fête du génie — Celebration of Talent

fête du travail — Celebration of Labour

fête de l’opinion — Celebration of Convictions

fête des récompenses — Celebration of Honors

fête de la Révolution — Celebration of the Revolution (Leap Day)

As each month was exactly 30 days, they also divided each month into three ‘décades’ of 10 days each. This was meant to act as a substitute for the 7-day week. It can be understood as the broader tendency of the period to decimalize things, having units of measurement, currency, etc. to all be based around the number 10. It also came as part of an effort to de-Christianize France.

There are many points to admire here. The best advantage of the French Republican calendar is that months are now a consistent unit of time. Treating the left-over days as holidays is also a nice touch. Picking the Autumnal Equinox as the start of the year also adds astronomical significance to the actual beginning of the year. A solar year is based on, as we discussed, the position of the Sun, but we currently start the year when the Sun is at a completely arbitrary point in the sky.

However, there are some clear disadvantages as well, the most glaring of which is the 10-day week. This was unpopular with workers who, instead of getting one day off out of every seven, they now got on day off out of every ten plus a half day in the middle.

Obviously, this is not strictly necessary. Especially if we are imagining the next calendar change to coincide with a socialist revolution, we should expect a massive reduction of the work-week regardless of whether the week is seven or ten days long. Still, disrupting the regular pattern of the week would be one of the harder points of transition between any calendar system. I will take these practical difficulties as obvious and instead provide a few other reasons why we might still prefer a 7-day week.

In Defense of the 7-Day Week

Besides all the practical difficulties that would come with switching away from a 7-day week, the best reason to oppose switching away from the 7-day week is the difficulties it would create for religious observances. This was, of course, part of the point for the French Republican calendar as part of their more general anti-clericalism, but this would obviously not only affect Christian observances on Sundays, but Jewish observances for the Sabbath.

Ideally, the society of the future will find itself able to accommodate many different schedules and patterns of scheduling, so perhaps this won’t be as much of an issue in the future. However, there is so little arguing in favor of the 10-day week, and this is such a major flaw for how this would affect our modern society, I see this point as fatal to any objection to the 7-day week.

On top of this, the 7-day week actually maintains the general calendar practice of being based on astronomical bodies, although in a more indirect way. Each day of the week is actually named after one of the seven classical planets: the Sun (or Sol), the Moon (or Luna), Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, Venus, and Saturn. In English this is obvious for Sunday (the Sun), Monday (the Moon), and Saturday (Saturn), but it is true of the rest as well thanks to the practice of interpretatio germanica.

Tuesday is named after the god Týr (Týr’s day) who was identified with the Roman god Mars, and by extension the planet.

Wednesday refers to Odin, spelled in Old English as Wōden, who was identified with the Roman god Mercury since they are both psychopomps.

Thursday refers to Thor, who was identified with the Roman god Jupiter as a god of lightning.

Friday is named after the goddess Frigg, the wife of Odin identified with the goddess Venus.

The association between the days of the week and the classical planets becomes even This is more obvious when you look at the days of the week in other the Romantic languages. Consider the days of the week in French:

Dimanche (Lord’s Day)

Lundi (Luna)

Mardi (Mars)

Mercredi (Mercury)

Jeudi (Jupiter)

Vendredi (Venus)

Samedi (Sabbath)

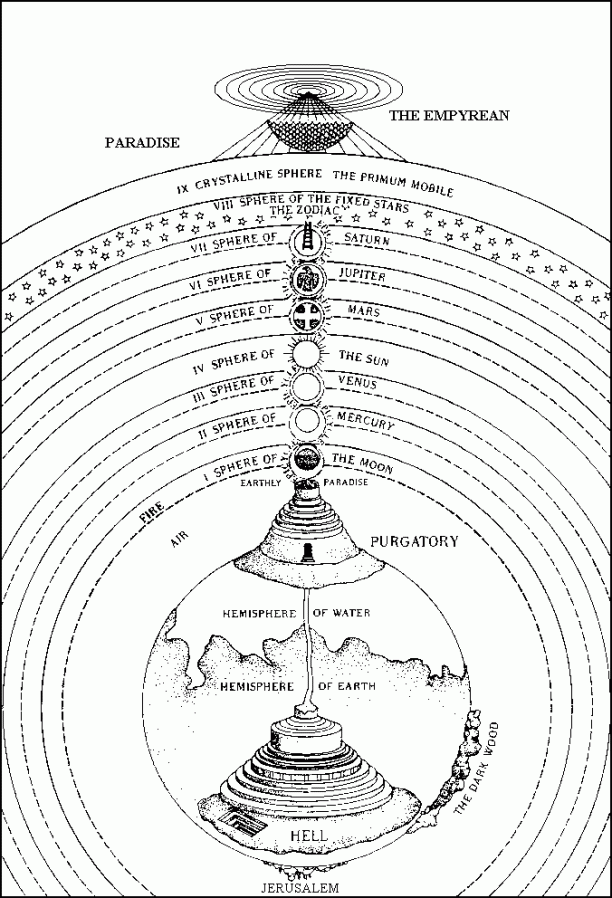

Interestingly, even the order of the days of the week line up in a way with the ancient view of the heavens. According to the geocentric Ptolemaic model of the universe, the Earth was surrounded by different spinning spheres. Working from the outermost edges of the universe inward you get these spheres:

The Primum Mobile

The Fixed Stars

Saturn

Jupiter

Mars

The Sun / Sol

Venus

Mercury

The Moon / Luna

Earth

Now obviously this order does not line up with the days of the week. But if you take the seven planets here (including the Sun and Moon), then place them in order around a great heptagram, you will actually see the days of the week traced out! We go from Sunday (Sun 6) to Monday (Moon 9) to Tuesday (Mars 5) to Wednesday (Mercury 8) to Thursday (Jupiter 4) to Friday (Venus 7) to Saturday (Saturn 3).

This is all neat nerd stuff that doesn’t provide any real practical benefits, but I take those as obvious for the 7-day week with little benefit to altering it. Instead, I point this out to give the 7-day week greater historical and even mystical significance, and showing a surprising way the calendar is based on astronomical bodies. It fits the theme.

Now the French Republican calendar didn’t need to divide up their months like that. Rather, they did that because it was a more convenient way to divide up a 30-day month into equal periods, and we cannot divide 30 by 7.

But this does indicate a way that we might improve the calendar beyond the French Republican version.

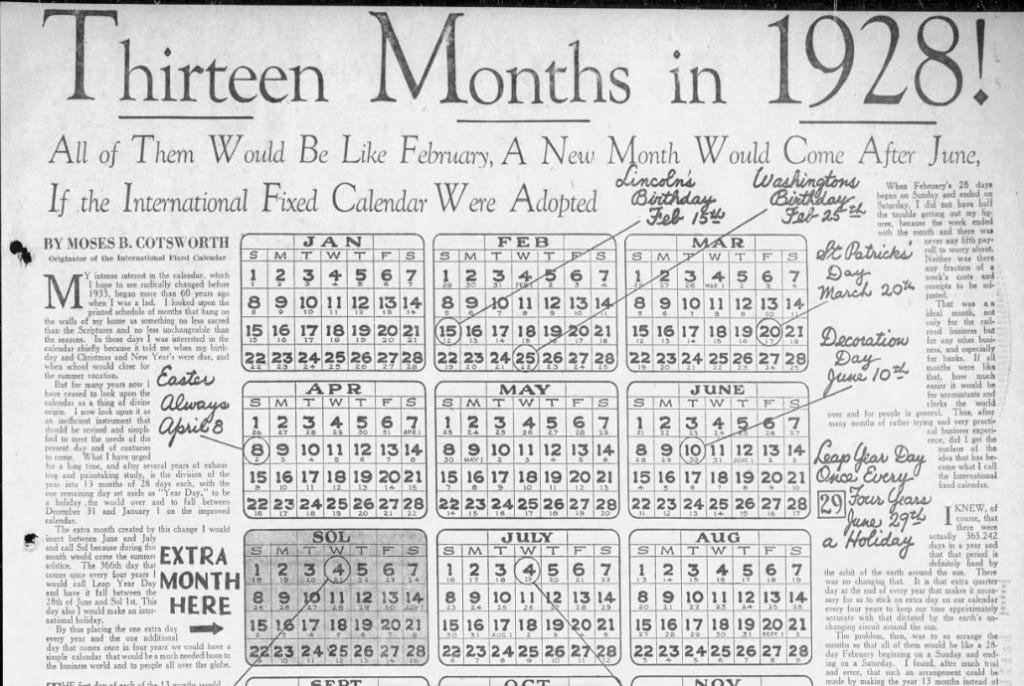

Introducing the 13-Month Year

We commonly estimate a month to be four weeks long, even though this is technically only true right now in February on non-leap years. February is 28 days long, which is exactly four weeks. So my proposal here is to add in a 13th month, as 13 x 28 = 364. We can therefore fit 13 months into the year with only a single day left out as a remainder instead of five! This way we can both make months a consistent unit of time, exactly 28 days long, we keep the 7-day week, and months are now a unit of time perfectly compatible with the week!

One might try to defend the 12-month year on the grounds that 12 is a highly composite number while 13 is a prime number. We can easily talk about things like a half-year or quarter year when looking at 12 months than we can with 13 months. And these are frequently used ways to divide the year, so their loss would not be a trivial matter. But by setting the start of the year to the beginning of Spring, we have addressed this issue for the most part. While the months themselves could not be used to divide the year into halves or fourths, the seasons will already be dividing the year accordingly. We therefore maintain a natural way to divide the year into quarters or halves. Since months are a consistent length of time, this also allows people to use that as a point of reference for other ways one might divide the year in four (e.g. a month before the first day of each season).

I am not the first person to notice advantages of a 13-month year and cannot take credit for it. The International Fixed Calendar was proposed in 1902, adding in the 13th of ‘Sol’ between June and July. The single remainder day was called ‘Year Day’ as the last day of the year, and Leap Day was placed between June and Sol.

The International Fixed therefore divides the year as follows:

January

February

March

April

May

June

(Leap Day)

Sol

July

August

September

October

November

December

Year Day

Having 13 months would have an additional benefit. Since each month is made of exactly four weeks, this also means that each month within the year will start and end on the same day of the week. As seen in the above photo, each month begins on Sunday and ends on Saturday.

However, the International Fixed Calendar is only able to keep this consistent between years by excluding Year Day and Leap Days from being counted as any day of the week. Just like they are excluded from any month, they are now excluded from the week.

The idea of every month beginning and ending on the exact same day is cool, but we run into the same religious objection argument. If we functionally make one or two weeks out of the year 8 or 9 days long, what expectation is being placed on, say, observant Jews who were commanded to rest on the seventh day?

I agree with a 13-month structure for the year, with 28 days or 4 weeks per month.

However, some further improvement can be made on the International Fixed Calendar. For starters, we will move Leap Day from the middle of the year to the end of the year, like was done in the French Republican calendar. On Leap Years, Leap Day will occur the day before Year Day to maintain its status as a celebration of the end of the year. In other words, the year would look like this:

January

February

March

April

May

June

Sol

July

August

September

October

November

December

(Leap Day)

Year Day

We have a basic outline for the year and how it is being temporally divided. I leave a few questions open:

How should the months be named?

On what day does the year begin?

The Names of the Months are Off

The prefix “octo-” refers to the number eight, as in “octopus”. Yet in the Gregorian calendar October is the 10th month of the year in the current system, not the 8th. Isn’t that strange? The International Fixed Calendar moves it in the wrong direction, making it the 11th month. You can see this with other months too. “Dec-” as in “decimal” refers to the number ten, yet December is the 12th month of the Gregorian calendar.

In fact, we can see this with September, October, November, and December. The Latin words for seven, eight, nine, and ten are “septem, octo, novem, decem.” It doesn’t take a genius to figure out that September, October, November, and December literally mean months seven, eight, nine, and ten. Somehow this got messed up along the way, with two additional months added without changing the names of the months accordingly.

Looking back at history, we can see this was the case with the Roman Calendar, which originally treated March as the first month of the year. In this original framing, we had the following months:

Martius (March)

Aprilis (April)

Maius (May)

Iunius (June)

Quintilis, later replaced with Iulius (July)

Sextilis, later replaced with Augustus (August)

September

October

November

December

As a brief note, Quintilis and Sextilis follow the patterns of September through December, literally referring to the Latin words for five (quinque) and six (sex). This was replaced with Iulius in reference to Julius Caesar, and Augustus in reference to Augustus Caesar.

It is clear form this that the months missing are January and February. They are our culprits for throwing off the Roman people’s basic counting skills.

To fix the calendar, we therefore need to do one of two things. Either we (1) change all the names of the months, or at least change September through December, or (2) we reorder the existing month names to restore at least September through December to their rightful spots.

Since we are adding a new 13th month, we will need at least one new month name compared to the Gregorian Calendar. For now, I will follow the pattern of the International Fixed Calendar and call this Sol.

The easiest fix for the calendar names then would be to do the following:

March

April

May

June

July

August

September

October

November

December

Sol

January

February

(Leap Day)

Year Day

We can see from this that September, October, November, and December have all been restored to their rightful place as months 7, 8, 9, and 10.

However, there are additional problems with this ordering as well. Most notably, the month of January is named after Janus, the god of beginnings and endings. If January is not going to be the first month anymore, it should be the last. In that case, we can switch the places of January and February for the following:

March

April

May

June

July

August

September

October

November

December

Sol

February

January

(Leap Day)

Year Day

The names of the other months generally don’t cause any issue due to their location.

‘Martius’ or March is named after Mars, god of war

‘Aprilis’ or April is named after ‘Apru’ or Aphrodite, goddess of beauty

‘Maius’ or May is named after Maia, the mother of Hermes

‘Iunius’ or June was named after Juno, the queen goddess

February is the only one here that might be considered an issue in this order. It was actually named after a festival that fell within it called Februa, later known as Lupercalia. Ideally, we would want the date of this festival to continue to fall within February, but that depends entirely on what day is picked for the start of the new year, which we will address later.

Personally, I would also object to the names July and August as continued veneration of emperors, something rejected by all who love freedom. This could be a simple change back to Quintilis and Sextilis, or we could introduce entirely new names.

We could also substitute names in from the French Republican calendar for the appropriate season. However, I think mixing names like that would be kind of tacky, and the names from the French Republican calendar in general are not great, referring to the weather patterns specifically for France, and therefore hardly working as a calendar that could or should be adopted by the entire world.

The Start of the Year

Since we are beginning the year in March, the question of what should be the first day of the year becomes all the more important.

If we have March 1st take place on January 1st of the Gregorian calendar, then we would be able to keep the numbering for the years consistent. However, the obvious drawback here is that, while we would be keeping the names of the months, this would put them greatly out of step with their current seasonal associations.

We could have March 1st of the new calendar correspond to March 1st of the Gregorian calendar. That would also be relatively simple, but March 1st in the Gregorian calendar is not a point of time of any great astronomical significance.

Instead, I propose that, just as the French Republican calendar began on the Autumnal Equinox, this new calendar will begin on the Spring Equinox. This already takes place in the month of March (on March 19th, 20th, or 21st), so it would be only a minor adjustment, and would also keep some of the other months more consistent with their placement in the Gregorian calendar.

I propose we set March 1st of the new calendar to fall on March 20th of the Gregorian calendar. For some reason it is popular to claim that March 21st is the first day of Spring despite the fact that this only happens a grand total of 2 times in the entire 21st century. Most of the time it is happening either on the 20th or the 19th in the Gregorian Calendar, and the days it happens on the 19th is due to Leap Day.

The Spring Equinox is a better point to begin the year in general. Not only is it a date of astronomical significance, but Spring also represents a time of rebirth and new life. It is a natural fit for the start of the year.

This would also mean that the start of the year would line up with the beginning of the Zodiac, as Aries begins on the Spring Equinox. Traditionally, the start of the Zodiac was also associated with the start of creation itself. Thus in Dante’s Inferno he refers to the constellation of Aries like this:

Temp’ era dal principio del mattino,

e ’l sol montava ’n sù con quelle stelle

ch’eran con lui quando l’amor divinomosse di prima quelle cose belle;

sì ch’a bene sperar m’era cagione

di quella fiera a la gaetta pelle[The time was the beginning of the morning,

And up the sun was mounting with those stars

That with him were, what time the Love DivineAt first in motion set those beauteous things;

So were to me occasion of good hope,

The variegated skin of that wild beast,]

What About Holidays?

By starting the year on the Spring Equinox, March 20th in the Gregorian calendar, we also can now address some questions about when holidays will land in the new calendar. I will assume Leap Days are not applying.

To get the first point out of the way, Februa would still be happening in February in the new calendar. In the Gregorian calendar it took place on February 15th. Comparing that with the new calendar, it now takes place on February 25th. So by starting the year on the Spring Equinox, we have also guaranteed the naming convention for the months remains consistent.

However, we face a somewhat strange question: Is what matters a holiday the exact day it lands on? Or its relation to the calendar?

If I wanted to find, say, Christmas in the new calendar, I can do so fairly easily. December 25th in the Gregorian calendar is actually equivalent to Sol 1st in the new calendar. (How thematically appropriate!) Valentine’s Day would now fall on February 23rd. St. Patrick’s Day would also be on January 27th. The date for Easter remains a mess in this system, as it would for any solar calendar. Easter happens on the first Sunday following the first full moon after the Spring Equinox. So the new calendar doesn’t fix that to any date, but by beginning the year around the Spring Equinox it might make finding it easier.

But what about April Fool’s Day? April 1st in the Gregorian calendar is March 13th in the new calendar. But the new calendar also has its own April 1st which would be April 17th in the Gregorian calendar. Which day should it be? A similar issue exists for May Day or International Labor Day, which falls on May 1st. Or even worse, what about Cinco de Mayo? There are no great answers here, only what people decide makes the most sense. These difficulties are inherent to changing the calendar like this.

Halloween faces its own challenge too since it fell on October 31st in the Gregorian calendar, but the new calendar doesn’t have a 31st for any month whatsoever! We could celebrate it on October 28th in the new calendar, or it could be celebrated on November 2nd.

How should we transition?

So far, we have described the basic outline of the new calendar, examining how it divides the solar year. I have left aside the minutia of how this could be maintained in a series of Leap Days except to indicate what part of the year is should fall. I have not covered other adjustments, such as the use of the leap second.

For my complaints about the Gregorian calendar, it does seem to do an admirable job keeping pace with the Sun. The typical tropical solar year takes around 365.2422 days, while average the Gregorian calendar year takes 365.2425 days. This is because of Leap Days come once every four years, except in years that are divisible by 100 (i.e. 1800, 1900, 2000, etc.).

One point I have left off here so far is the counting of the years. Currently we use the Common Era, placing us in the year 2025 at the time I am writing this. The Common Era is a secularized version of Anno Domini (AD), keeping the same numbering system while removing its explicit connection to Christianity.

In the socialist world to come, the people may decide to declare a new era has arrived, and therefore resetting our system of counting years. For now I will assume that the Common Era would be maintained though.

The issue here is that this new calendar will begin counting years on a different date than the Gregorian calendar. Let’s say that we switch to this new calendar system today. I am writing this on April 11th, 2025, so in the new calendar this is actually March 23rd, 2025. However, when the Gregorian calendar would change to January 1st, 2026, we would instead be Sol 8th, 2025. From the individual’s perspective, the year 2025 would also have two Januaries and two Februaries, although in reality the Gregorian Calendar would say that those months were actually part of 2024.

Beyond this, other changes I make would be more focused on the clock than the calendar. Getting rid of Daylight Savings is an obvious point. We could also consider having the day start at the average dawn of the Spring Equinox rather than at Midnight.

So we’ve solved the hard part of laying out the plan for a new calendar. Now all we need is a global worker revolution to implement it.

One solution is to have six 5-day weeks instead of three 10day weeks.

On week 1 of the month, people might work for three days and then take two off. On the second week, work for four days and get a day off. And the pattern would repeat.

Now this not work for Jews, who need to rest every seven days. But we could tweak the weeks a little bit : work three days (with a two day break) in week 1, then work one day on week 2 and take a break the next day, before working for three more days.

Three days of labor + two rest days + another work day + another rest day = seven. Jewish workers can rest on the seventh day.