Explaining Geoffrey Kay's "Why Labour is the Starting Point of Capital" to Myself

Thoughts on Kay’s Paper

My usual method of notetaking, especially for complex or jargon-heavy works, is to try and rewrite what I read to explain it back to myself in my own words, or adding in explanations and notes as necessary. Then, in sections like this, I try to resummarize those notes back to myself yet again. I’ve found this useful, especially when I need to go over things or explain the main ideas of a work to other people like in a radical book club. I hope some others might also get some use from these notes/restatements/summaries/whatever you want to call them.

Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk’s critique of Marx in Karl Marx and the Close of his System (1896) stands out as one of the best known criticisms of Capital, calling out points like the ‘transformation problem’ and highlighting what seem like very reasonable concerns with how Marx structures his argument in the first chapter of Capital.

Kay’s paper here strikes me as one of the better responses to Bohm-Bawerk, closely engaging his own words in a way similar to how Bohm-Bawerk closely followed Marx. He builds the issues found here into a wider gulf in methodology between Marx and the neo-classical school that also influences things, and calls out how other Marxist responses fail to notice these problems, ‘poisoning’ Marxism from within.

An essential part of this paper then requires Kay to provide an alternative reading of Marx’s understanding of things like abstract labor and the nature of value. Here I think Kay falls short of the analysis provided by Diane Elson in her Value Theory of Labour. She builds off Kay’s work in good ways while also calling out some points of weakness, especially regarding Kay’s understanding of abstract labor as specific to capitalism. While Kay wants to emphasize something as lacking ‘reality’ or ‘existence’ unless it is given some kind of ‘practical truth,’ Elson is more accepting of it while pointing out that labor need not take on the same form. There is therefore no issue with abstract labor belonging to every epoch of history, or with Marx’s comments indicating this, even if value as a category is unique to capitalism.

Reviewing Kay’s argument, we begin with the transformation problem as an apparent contradiction between Volumes 1 and 3 of Capital. In Volume 3 Marx argues that the prices of commodities systematically deviate from their value according to the organic composition of capital. This seems out of line with the argument given at the very beginning of the first volume, where Marx deduces the existence of value from the exchange of commodities. It seems that if commodity exchange is not an exchange of equal values, as Volume 3 claims it is not, then the foundation of Marx’s ‘system’ crumbles.

Seeing this contradiction, Bohm-Bawerk concludes there must be some flaw in Marx’s argument. But while the ‘middle’ section seems untouchable to him, the flaw must instead be found in his initial premises that establish his value theory. Bohm-Bawerk advances at least three critiques:

Bohm-Bawerk accuses Marx of ‘rigging’ his argument by excluding non-commodities like virgin soil from consideration, despite the fact that they too are exchanged on the market, so that he can claim that these things share the property of being ‘products of labor.’ If exchange itself were implying this, then this exclusion appears to be entirely arbitrary. Since Marx agrees that non-commodities do exchange on the market without having value, as they are not products of labor, Kay needs to find some non-arbitrary reason why Marx might have excluded them.

Bohm-Bawerk understands Marx’s argument to be finding labor as the common factor that forms the substance of value by process of elimination. He claims that use-value cannot be the foundation of value, and then claims the only other possible option is that they are products of labor. Bohm-Bawerk objects that there are other common features we can name that haven’t been excluded. Kay needs to either show Bohm-Bawerk misunderstands Marx’s argument or show how these alternative common features may be reduced down to labor or use-value, or are otherwise invalid.

Bohm-Bawerk claims that the way Marx moves from concrete labor to abstract labor could be used equally to move from particular use-values to use-value in general. Marx’s reasoning for eliminating use-value as the common factor that can form the substance of value is therefore invalid. The same argument, if reversed, could be used to eliminate labor as a possibility in favor of use-value. Kay needs to show why this is not the case, and spends the bulk of the essay here explaining the differences between the ‘formalist’ method of the neo-classical school and Marx’s dialectics, ultimately showing how the specific nature of labor and use-values makes Marx’s moves valid in one case where they would be invalid in the other.

Against the first point, Kay argues that we may exclude non-commodities from consideration because, both historically and logically, commodity exchange must develop prior to non-commodity exchange. If non-commodities are going to gain a standardized money-price, then this implies there is already a well-established system of property rights and markets that allows this price to be paid in money, and this only happens when the dominant form of production is commodity production. Otherwise rent might just be paid in kind, such as serfs giving up a part of their harvest to their lord. The free gifts of nature are only ‘commodified’ like this in a system of commodity production. They are derivative and therefore may non-arbitrarily be excluded from our initial analysis.

I think Kay’s answer here is acceptable, but might leave out some points highlighted by Elson. In particular, the object of Marx’s theory was not ultimately to explain prices, but to understand how labor is being determined, taking on this particular form, within capitalism. He is therefore beginning with the simplest form the product of labor presents itself as and the social relations this implies.

Against the second point, Kay seems to rush past things a bit. He argues that some of the alternatives Bohm-Bawerk gives are ‘invalid.’ For example, if we are trying to explain what common factor is being expressed is being expressed in exchange, it does us little good to say they are subject to supply and demand since this merely repeats that they are an exchange-value. Likewise, as for being a cause for expense by the producer, the main expense seems to be labor.

I think a more elaborate defense could be deserved here. We might try to follow up that by explaining supply and demand, we also explain equilibrium where these commodities ‘equal’ one another, meaning nothing further needs to be appealed to. Likewise, some resources are genuinely scarce besides labor.

But I think Kay follows up with this, in his response to the third point, by attacking how Bohm-Bawerk thinks Marx’s ‘process of elimination’ is working out, making it something more ‘positive’ than he assumed. In that case, it wouldn’t be so much of a problem that Marx did not rule out every possible common factor they shared, even if eliminating use-value helps to bolster his argument.

Moving on to this third point, Kay summarizes Bohm-Bawerk’s view of Marx’s argument by thinking that, in exchange, we see that a common factor is being expressed in different ways in each commodity. Thus a use-value appears as wood, iron, wheat, a coat, or whatever else. They differ from one another but are all use-values. Likewise, labor differs in its different forms as logging, mining, farming, tailoring, and so on. Marx seems to eliminate use-value being the common factor because of these differences, but does not eliminate labor, simply inventing this idea of ‘abstract labor.’

Kay thinks this is a ‘formalist’ way of looking at things, making an abstract model where we are working simply with names and symbols rather than directly engaging with the subject of our analysis. This is contrasted to the ‘dialectical’ method which never totally divorces itself from what it is studying.

For Marx, we cannot abstract from use-value this way because to talk of something’s use-value is nothing but talking about how its particular material form can be made use of. There is no general use-value underneath it to appeal to.

But the obvious response to this is that labor too must exist in some particular form. Abstract labor is an aspect of labor, not a distinct kind of labor from concrete labor. And Kay does have some trouble here explaining why Marx might describe abstract labor simply by appealing to the common features of all labor, such as being some expenditure of brain and muscle. It seems like we could equally say that all use-values are the satisfaction of some want.

Kay dismisses these comments from Marx as undialectical. Instead, he finds the strength of Marx’s argument by pointing out how labor is not merely an individual task, but part of the collective effort of society. He equates the term ‘abstract labor’ with ‘social labor,’ where we are producing for others in society and our labor is just considered a fraction of the total labor of society. When looked at this way, and the kind of social relation this implies, we can see that exchange is equating the products of our labor, where any particular kind of concrete labor can get us the product of any other particular kind of concrete labor.

I believe that Kay is right that this is a distinguishing feature of labor that is not found in use-value. In this exchange process, it is the difference, not the equality, in use-value that is being highlighted. Moreover, as Elson highlights, it is important that these things are being socially equated by some process, not just subjectively equated in the minds of the traders, which pushes us away from the mere mental state of those involved. When people enter the market, they find the product of their labor has this social substance that can be turned into any other product of labor. This argument is more positive than Bohm-Bawerk credits, which also helps address his second objection retroactively.

Elson rightly objects to some parts of Kay’s argument, namely the equation between abstract labor and social labor. She thinks there is some degree of overlap, with both being looked at ‘objectively’ in this way, but the focus of abstract labor adds in a quantitative dimension, focusing on our labor measured in labor-time as part of the total labor available in society, which merely considering our labor as social lacks. While Kay objected to making abstract labor common to all labor rather than specific to capitalism, his own description of social labor seems like it would apply equally to socialism. This seems to confirm things for Elson. It also helps to explain why Marx might be focused on aspects of labor, like it taking time and effort, that is common to all labor in all societies without saying that value is common to all societies.

But an important point from here is that, for abstract labor to have ‘practical truth’ and not just be a rational abstraction, it needs to be embodied in some way. This does seem to be something more unique to capitalism, at least as it is embodied by the value-form. For value to be some kind of social substance, it needs some kind of immediate appearance, even if we don’t immediately understand what lies beneath that appearance. Marx argues this is provided by the equivalent form within the exchange, as the value of our product of labor is represented in the use-value it can get for us, particularly in the universal equivalent of money. As everything is given a money-price, this practically demonstrates that all of these commodities are being socially equated.

Having addressed Bohm-Bawerk’s objections to Marx’s argument in chapter 1 of Capital, we still need to explain the transformation problem. How can Volume 1 be made consistent with Volume 3?

The first major thing Kay needs to establish is that Marx’s argument in the first chapter of Capital doesn’t actually depend on exchange demonstrating that things have equal magnitudes of their common substance. He primarily argues this by showing that the argument given above, where the product of labor can be turned into any other type of labor at set ratios, doesn’t require them to have the same magnitude. They need the same ‘quality’ of being products of labor, but not necessarily the same ‘quantity’ for how this amount is being measured. That value is represented by the use-value of what it’s trading for especially highlights it, since we never really see the value of the equivalent form, especially of the universal equivalent, except as the laundry list of everything else it might exchange for. This allows for incongruity between the value of what is being exchanged.

This response only seems partially satisfactory to me. The point that we don’t see the value, only the use-value, of the equivalent is a very strong point. However, this does not explain all the times Marx does seem to directly point out that we are finding something in exchange with an equal magnitude. If that isn’t really implied by any of this, why would Marx include it?

Again, Elson seems to provide a better answer here, emphasizing that we do have the appearance of equal magnitudes of value in exchange, which in a few places at least Marx seems careful enough to include. We do not challenge that appearance yet until chapter 3 though, after our theory of value is further developed and we introduce influences that can change how value is being distributed between capitals. This is, as Elson describes it, a move away from looking at things merely as the product of labor toward looking at them as the product of capital.

Finally, Kay considers a potential objection Bohm-Bawerk might have raised if he had heard this answer to the transformation problem. Namely, Marx’s theory of surplus-value seems to rely on the commodity of labor-power exchanging at its value. If it didn’t, then maybe Marx’s theory of value could be saved, but not of surplus-value.

Kay’s response here is to point to the structure of Marx’s argument, working from the existence of surplus-value to a tendency for capitalism to push wages down to the value of labor-power. So any hypothetical objection from Bohm-Bawerk would be misplaced. I think this answer aligns well with the point from Elson that Marx is not presenting his theory of value as a proof of exploitation. That is instead seen simply from the monopolization of the means of production away from the workers. Since exploitation can be established on different grounds, this line of argument is valid.

Restatement of Kay’s Paper

Introduction

Who was Böhm-Bawerk?

Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk (1851 - 1914) was a 19th century intellectual who is better remembered today for his criticism of Marx than any positive contribution he made to economics. While he holds a place in history as a pioneer of neo-classical economic theory, it is his criticisms in Karl Marx and the Close of his System (1896) that really lets him stand out. All serious critiques of Marx’s ideas of value and surplus-value from bourgeois economists tend to just fall back to the same points Bohm-Bawerk made.

(Note: I would add that today Bohm-Bawerk is also decently well known among propertarians who obsess over the ‘Austrian’ school of economic thought. Bohm-Bawerk was the teacher of Ludwig von Mises, who was the teacher of Murray Rothbard, who founded ‘anarcho’-capitalism and was extremely influential of the misnamed Libertarian Party in the USA. Even in this circle though, not many read Bohm-Bawerks economic works itself.)

Bohm-Bawerk’s criticism is so well remembered in part because he pays very close attention to the text of Capital, rather than just presenting an ideological handwave. He also raised the ‘transformation problem,’ which is often seen as one of the great weaknesses of Marx’s theory. Finally, he also presented a systematically positivist critique of Marx, challenging him on his very method.

Bohm-Bawerk wrote his criticism after the third and final volume of Capital was published posthumously. Hence it represents the ‘close’ of Marx’s system. But Bohm-Bawerk mostly finds this relevant because he thinks the third volume of Capital contradicts the first.

A Contradiction Between Capital Volumes 1 and 3?

(Note: I will deviate a bit from the text of Kay’s paper here to elaborate on Bohm-Bawerk’s critique of Marx, providing fuller context.)

In Capital Volume 3, Marx argues that the average rate of profit causes the price of commodities to systematically deviate from their values. As different industries have different organic compositions of capital (i.e. different ratios between constant and variable capital), the same rate of surplus-value will cause some industries to produce more surplus-value than others.

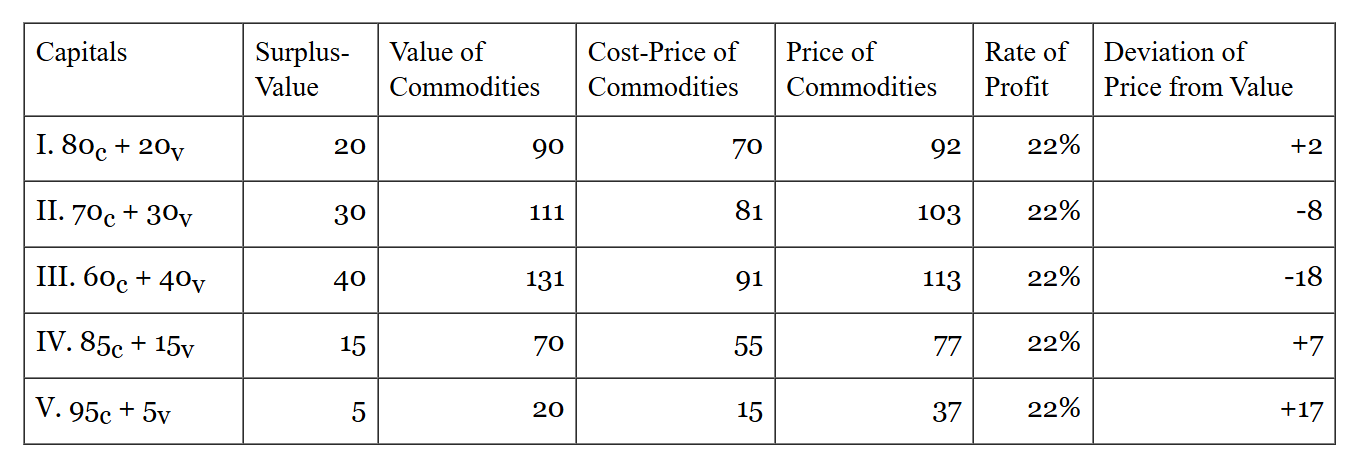

As an example, here is a chart Marx provides in Capital, Vol. 3, Ch. 9:

As we can see here, each capital on the left is equal to 100 but is divided between constant and variable capital at different proportions. Now the variable capital is what is being spent on labor-power. As surplus-value is coming from the exploitation of the workers, more labor-power being purchased means, at the same rate of surplus-value, more surplus-value is being produced. If the value of each product equaled its price, then the rate of profit for each capital will be different, with industries that are proportionally hiring more labor-power having a higher rate of profit.

But this is not what we actually tend to see in practice. If capitalists see they can get higher profits in one industry compared to another, they will switch their investments to that industry. The tendency in capitalism then is actually for the rate of profit to equalize across industries, moving to their average. But as they are retaining these different ratios between constant and variable capital, this is only possible if the prices of these commodities are deviating from their values.

Marx therefore follows up with this chart a few paragraphs later:

Each capital has moved from their different rates of profit to their average of 22%. As each capital is equal to 100, this means that the price of each commodity is going to be 22 higher than its cost-price. (The cost-price here is varying more wildly because Marx is assuming each constant capital is divided up at different proportions between fixed and circulating capital. Don’t worry about it.)

It follows that, in capitalism, commodities do not tend to exchange at their values. Instead they systematically deviate from it.

But this conclusion seems to be in tension with the argument Marx gives for his theory of value in the first place at the very start of Capital Volume 1.

As Bohm-Bawerk’s critique, and Kay’s defense, deal with careful reading of the argument Marx gives in chapter 1, I will quote it here at length for reference:

A given commodity, e.g., a quarter of wheat is exchanged for x blacking, y silk, or z gold, &c. – in short, for other commodities in the most different proportions. Instead of one exchange value, the wheat has, therefore, a great many. But since x blacking, y silk, or z gold &c., each represents the exchange value of one quarter of wheat, x blacking, y silk, z gold, &c., must, as exchange values, be replaceable by each other, or equal to each other. Therefore, first: the valid exchange values of a given commodity express something equal; secondly, exchange value, generally, is only the mode of expression, the phenomenal form, of something contained in it, yet distinguishable from it.

Let us take two commodities, e.g., corn and iron. The proportions in which they are exchangeable, whatever those proportions may be, can always be represented by an equation in which a given quantity of corn is equated to some quantity of iron: e.g., 1 quarter corn = x cwt. iron. What does this equation tell us? It tells us that in two different things – in 1 quarter of corn and x cwt. of iron, there exists in equal quantities something common to both. The two things must therefore be equal to a third, which in itself is neither the one nor the other. Each of them, so far as it is exchange value, must therefore be reducible to this third.

A simple geometrical illustration will make this clear. In order to calculate and compare the areas of rectilinear figures, we decompose them into triangles. But the area of the triangle itself is expressed by something totally different from its visible figure, namely, by half the product of the base multiplied by the altitude. In the same way the exchange values of commodities must be capable of being expressed in terms of something common to them all, of which thing they represent a greater or less quantity.

This common “something” cannot be either a geometrical, a chemical, or any other natural property of commodities. Such properties claim our attention only in so far as they affect the utility of those commodities, make them use values. But the exchange of commodities is evidently an act characterised by a total abstraction from use value. Then one use value is just as good as another, provided only it be present in sufficient quantity. Or, as old Barbon says,

“one sort of wares are as good as another, if the values be equal. There is no difference or distinction in things of equal value ... An hundred pounds’ worth of lead or iron, is of as great value as one hundred pounds’ worth of silver or gold.”

As use values, commodities are, above all, of different qualities, but as exchange values they are merely different quantities, and consequently do not contain an atom of use value.

If then we leave out of consideration the use value of commodities, they have only one common property left, that of being products of labour. But even the product of labour itself has undergone a change in our hands. If we make abstraction from its use value, we make abstraction at the same time from the material elements and shapes that make the product a use value; we see in it no longer a table, a house, yarn, or any other useful thing. Its existence as a material thing is put out of sight. Neither can it any longer be regarded as the product of the labour of the joiner, the mason, the spinner, or of any other definite kind of productive labour. Along with the useful qualities of the products themselves, we put out of sight both the useful character of the various kinds of labour embodied in them, and the concrete forms of that labour; there is nothing left but what is common to them all; all are reduced to one and the same sort of labour, human labour in the abstract.

Let us now consider the residue of each of these products; it consists of the same unsubstantial reality in each, a mere congelation of homogeneous human labour, of labour power expended without regard to the mode of its expenditure. All that these things now tell us is, that human labour power has been expended in their production, that human labour is embodied in them. When looked at as crystals of this social substance, common to them all, they are – Values. (Marx, Capital, Vol. 1, Ch. 1)

Bohm-Bawerk interprets this argument along the following lines:

Commodities have exchange-values, trading for other goods on the market.

When two commodities have the same exchange-value, trading for one another, this implies there “exists in equal quantities something common to both.”

This ‘common something’ is either (a) that they are use-values or (b) that they are products of labor.

It cannot be that they are use-values because commodities have different use-values, doing different things.

Therefore, it is that they are products of an equal amount of labor.

However, they are products of different concrete labors (e.g. carpentry, tailoring, spinning, etc.).

Therefore, they are being equated only as products of abstract labor, the common features of all labor.

We call this ‘common something’ Value.

Because he interprets Marx this way, Bohm-Bawerk argues that Volume 1 and 3 of Capital fundamentally contradict one another.

In Volume 1 we are told that things have the same exchange-value implies they are equal values. But in Volume 3 we are told that the price of commodities, their exchange-values expressed in money-terms, can deviate wildly from their value, and by different amounts in different industries. Things with the same exchange-value can therefore have wildly different values. This is not coming merely from market-fluctuations or the influence of the velocity of currency either, which Marx does allow for in Volume 1, but a permanent feature of the economy.

In the first volume it was maintained, with the greatest emphasis, that all value is based on labour and labour alone, and that values of commodities were in proportion to the working time necessary for their production. […] Apart, therefore, from temporary and occasional variations which "appear to be a breach of the law of the exchange of commodities" (i. 142), commodities which embody the same amount of labour must on principle, in the long run, exchange for each other. And now in the third volume we are told briefly and drily that what, according to the teaching of the first volume must be, is not and never can be; that individual commodities do and must exchange with each other in a proportion different from that of the labour incorporated in them, and this not accidentally and temporarily, but of necessity and permanently.

I cannot help myself; I see here no explanation and reconciliation of a contradiction, but the bare contradiction itself. Marx's third volume contradicts the first. The theory of the average rate of profit and of the prices of production cannot be reconciled with the theory of value. (Bohm-Bawerk, Karl Marx and the Close of his System, Ch. 3)

Even though Volume 3 contradicts Volume 1, Bohm-Bawerk does not think this is due to any error on Marx’s part. On the contrary, he is rather impressed with the internal consistency in the ‘middle’ part of Capital between these two arguments.

In this middle part of the Marxian system the logical development and connection present a really imposing closeness and intrinsic consistency. Marx is free to use good logic here because, by means of hypothesis, he has in advance made the facts to square with his ideas, and can therefore be true to the latter without knocking up against the former. And when Marx is free to use sound logic he does so in a truly masterly way. However wrong the starting point may be, these middle parts of the system, by their extraordinary logical consistency, permanently establish the reputation of the author as an intellectual force of the first rank. (Bohm-Bawerk, Karl Marx and the Close of his System, Ch. 4)

It follows that if Marx’s reasoning was entirely valid, yet we are ending in a contradiction, there must have been something wrong with the premises he was reasoning from.

Despite the title of Bohm-Bawerk’s critique emphasizing the ‘close’ of Marx’s ‘system’ in Volume 3, his actual attack against Marx is directed at the very beginning of Volume 1 and Marx’s argument for his theory of value. In doing so, he also hopes to open the way for presenting his alternative theory of value more in line with neo-classical economics.

Likewise, Geoffrey Kay, as a defender of Marx, needs to demonstrate that Bohm-Bawerk’s critique of Marx is inaccurate or based on a misreading, as well as demonstrate how an accurate understanding of Marx’s argument is not vulnerable to these criticisms.

The ‘Error’ in the Marxist System

How Bohm-Bawerk Understands Marx’s Argument

Bohm-Bawerk reads Marx’s method of discovering value to be a ‘purely logical proof.’ Following Aristotle, Marx held that since commodity exchange is a quantitative relationship, this implies there is some common factor being used to equate them. Marx then uses a ‘purely negative proof,’ i.e. using the process of elimination, to demonstrate that this factor is labor.

Bohm-Bawerk does not prefer this kind of ‘negative’ approach, but doesn’t inherently object to it either, so long as we take care to truly consider and eliminate every alternative.

Now Marx, instead of proving his thesis from experience or from its operant motives–that is, empirically or psychologically–prefers another, and for such a subject somewhat singular line of evidence–the method of a purely logical proof, a dialectic deduction from the very nature of exchange. Marx had found in old Aristotle the idea that "exchange cannot exist without equality, and equality cannot exist without commensurability" (i. 35). Starting with this idea he expands it. He conceives the exchange of two commodities under the form of an equation, and from this infers that "a common factor of the same amount" must exist in the things exchanged and thereby equated, and then proceeds to search for this common factor to which the two equated things must as exchange values be "reducible" (i. 11).

[…]

Marx searches for the "common factor" which is the characteristic of exchange value in the following way. He passes in review the various properties possessed by the objects made equal in exchange, and according to the method of exclusion separates all those which cannot stand the test, until at last only one property remains, that of being the product of labour. This, therefore, must be the sought-for common property.

This line of procedure is somewhat singular, but not in itself objectionable. It strikes one as strange that instead of submitting the supposed characteristic property to a positive test–as would have been done if either of the other methods studiously avoided by Marx had been employed–Marx tries to convince us that he has found the sought-for property, by a purely negative proof, viz., by showing that it is not any of the other properties. This method can always lead to the desired end if attention and thoroughness are used–that is to say, if extreme care is taken that everything that ought to be included is actually passed through the logical sieve and that no mistake has been made in leaving anything out. (Bohm-Bawerk, Karl Marx and the Close of his System, Ch. 4)

Understanding this, Bohm-Bawerk argues that Marx has made at least three major errors in this proof, rendering it invalid. He accuses Marx of the following:

Marx rigged the results of this negative method to include ‘products of labor’ as a common factor by limiting his focus to commodities, leaving out other non-commodities that are exchanged on the market but are not products of labor, like untouched land.

Marx did not actually eliminate every common factor shared between commodities, instead only considering use-value.

Marx’s argument for eliminating use-value is invalid and, if reversed, could just as easily be used to eliminate labor as a common factor to ‘discover’ use-value as the source of value.

We will deal with each objection in turn.

Did Marx rig his results by leaving out other goods exchanged on the market?

Marx begins Capital by analyzing commodities. But by a ‘commodity’ he does not mean any and every good which is traded on the market. While a commodity is something with both a use-value and an exchange value, it does not follow that anything with a use-value and an exchange-value is a commodity. Since Marx is arguing that all commodities are products of labor, it is clear that the ‘free gifts of nature’ like virgin soil, forests, minerals, and so on are not commodities, despite having a use-value and a price at which they are bought and sold on the market.

Bohm-Bawerk argues that, by leaving out these free gifts of nature, Marx has rigged his argument. He wanted to conclude that labor was the source of value, the common property found in exchange, so limited his consideration to only the exchange of products of labor. If he were reasoning legitimately, deducing the existence of value from the concept of exchange, he should have considered all exchangeable things.

If Marx had not confined his research, at the decisive point, to products of labour, but had sought for the common factor in the exchangeable gifts of nature as well, it would have become obvious that work cannot be the common factor. If he had carried out this limitation quite clearly and openly this gross fallacy of method would inevitably have struck both himself and his readers; and they would have been forced to laugh at the naive juggle by means of which the property of being a product of labour has been successfully distilled out as the common property of a group from which all exchangeable things which naturally belong to it, and which are not the products of labour, have been first of all eliminated. The trick could only have been performed, as Marx performed it, by gliding unnoticed over the knotty point with a light and quick dialectic. But while I express my sincere admiration of the skill with which Marx managed to present so faulty a mode of procedure in so specious a form, I can of course only maintain that the proceeding itself is altogether erroneous. (Bohm-Bawerk, Karl Marx and the Close of his System, Ch. 4)

This is a clever attack. It simultaneously undermines Marx’s argument with a clear counter-example and sets Bohm-Bawerk to defend an alternative view, namely arguing that the real common factor shared by these goods is their utility and scarcity.

This is also a clear enough omission that, if Marx really does fall for this kind of criticism, it’s hard to read it as anything but intentional. Their exclusion from the ‘logical sieve’ here seems like a deliberate and arbitrary omission, one which Marx made from purely ideological motivations, and then tried to obscure so people could not recognize what he was doing.

That Marx was truly and honestly convinced of the truth of his thesis I do not doubt. But the grounds of his conviction are not those which he gives in his system. They were in reality opinions rather than thought-out conclusions. […]

He knew the result that he wished to obtain, and must obtain, and so he twisted and manipulated the patient ideas and logical premises with admirable skill and subtlety until they actually yielded the desired result in a seemingly respectable syllogistic form. (Bohm-Bawerk, Karl Marx and the Close of his System, Ch. 4)

Is there any truth to this criticism?

Certainly Marx recognized that non-commodities, like the free gifts of nature, are in fact bought and sold on the market and have a price. Marx discusses this point himself a few chapters into Capital:

Objects that in themselves are no commodities, such as conscience, honour, &c., are capable of being offered for sale by their holders, and of thus acquiring, through their price, the form of commodities. Hence an object may have a price without having value. The price in that case is imaginary, like certain quantities in mathematics. On the other hand, the imaginary price-form may sometimes conceal either a direct or indirect real value-relation; for instance, the price of uncultivated land, which is without value, because no human labour has been incorporated in it. (Marx, Capital, Vol. 1, Ch. 3)

So Marx is definitely leaving these things out of consideration in his first chapter as he claims they “in themselves are no commodities” and agrees they can “have a price without having value.” Why did he do this?

Now it is true that only things that can satisfy human desires, i.e. use-values, may be exchanged, and this depends on the physical properties of these objects. Trees from a virgin forest can act as fuel, as building material, etc. because of their physical makeup. They are, by their very nature, use-values.

But they are not, by their nature, exchange-values. To be exchanged, they need to be something else: private property.

Just because a tree is a use-value doesn’t tell me that the people using it will be buyers. For that we’d need additional assumptions, namely that the users are being prevented from appropriating the trees directly. Or, to say the same thing, the trees must belong to someone whose claim over them is socially recognized and substantiated. For something to be traded on the market, there needs to already be a market and a system of property relations.

Kay argues that the free gifts of nature have historically only acquired a money-price on the market after the development of commodity production. For example, land only gained its price of money-rent after agricultural production had largely shifted into commodity production. Paying rent in money only became standardized after it became normal for the product of people’s labor to be sold off for money.

True, sometimes commodity production onto a society which did not have it from the outside, as can be seen in the process of colonization. In these cases, we might see the demand for money-rent becoming the tool to push workers into commodity production. But this doesn’t challenge our general point since that only looks at these territories in isolation. Commodity-production proceeded money-rent in the outside places this shift is being imposed from.

This isn’t a historical accident. Commodity production needs to proceed money-rent because it is dependent on it. Ricardo demonstrated this, and this was incorporated into the neo-classical theory of which Bohm-Bawerk was a pioneer. The size of rent isn’t determining the prices of commodities. Instead we have the reverse, with the size of rent being determined by the prices of commodities.

(Note: I believe Kay has in mind here Ricardo’s ‘law of rent.’ Ricardo argued in chapter 2 of his Principles that “Corn is not high because a rent is paid, but a rent is paid because corn is high; and it has been justly observed, that no reduction would take place in the price of corn, although landlords should forego the whole of their rent.” Some elaboration from Kay on this would have been nice, as would have some citations around the history of the money-rent of land, although I take his characterization to be generally accurate. I would also add that Bohm-Bawerk argued that the exchange of gifts of nature “would never have entered the head of Aristotle, the father of the idea of equality in exchange.” Why not though? Presumably because Bohm-Bawerk agreed with Kay that commodity exchange preceding the exchange of non-commodities!)

We can only examine the exchange of non-commodities after we have an understanding of the exchange of commodities. Marx’s exclusion of non-commodities from his analysis was therefore not an attempt by him to exclude it from his ‘logical sieve.’ There was actually very good reason to leave it out, and these reasons line up with the general thinking about political economy from Marx’s time as well as from the very economic school Bohm-Bawerk is representing.

(Note: I believe Kay’s answer here is only partially satisfactory. He gives a very good reason why we might, for non-arbitrary reasons, want to examine commodities before non-commodities, especially if we are presupposing familiarity with economic history and theory. But we have not established whether this was actually Marx’s reasoning. I think Marx’s reasoning is actually even more direct. As Diane Elson argued, Marx is beginning with an examination of only products of labor because the object of his theory is labor itself. It is only natural then that he begins with the how the product of labor is presenting itself in capitalism, where wealth appears as “an immense accumulation of commodities.” This also lines up with comments we see from Marx explaining his procedure:

What I proceed from is the simplest social form in which the product of labour presents itself in contemporary society, and this is the “commodity.” This I analyse, initially in the form in which it appears. Here I find that on the one hand in its natural form it is a thing for use, alias a use-value; on the other hand, a bearer of exchange-value, and from this point of view it is itself an “exchange-value.” Further analysis of the latter shows me that exchange-value is merely a “form of appearance,” an independent way of presenting the value contained in the commodity, and then I start on the analysis of the latter. (Marx, Notes on Wagner)

Another issue with this response is that it only hints at how this impacts the rest of Marx’s argument. Sure, we may need to study commodity exchange before we can understand non-commodity exchange, but if Marx’s argument is that all exchange implies equality, and therefore commensurability, then it isn’t clear why the dependence of non-commodity exchange on commodity exchange matters. However, as we will see, Kay denies that this was Marx’s reasoning, especially when addressing Bohm-Bawerk’s third point of attack, so we will get to that point shortly.)

Did Marx ignore other common factors besides labor?

Bohm-Bawerk’s second attack is similar to the first. In the first attack he argued Marx’s argument failed because he did not consider all goods exchanged on the market, which would have included non-commodities. The second attack argues that Marx’s argument fail because he did consider all alternatives, even if we did limit our focus only to commodities, meaning his process of elimination did not eliminate every option.

By means of the artifice just described Marx has merely succeeded in convincing us that labour can in fact enter into the competition. And it was only by the artificial narrowing of the sphere that it could even have become one "common" property of this narrow sphere. But by its side other properties could claim to be as common.

[…]

The second step in the argument is still worse: "If the use value of commodities be disregarded"–these are Marx's words–"there remains in them only one other property, that of being products of labour." Is it so? I ask to-day as I asked twelve years ago: Is there only one other property? Is not the property of being scarce in proportion to demand also common to all exchangeable goods? Or that they are the subjects of demand and supply? Or that they are appropriated? Or that they are natural products? For that they are products of nature, just as they are products of labour, no one asserts more plainly than Marx himself, when he declares in one place that "commodities are combinations of two elements, natural material and labour." Or is not the property that they cause expense to their producers–a property to which Marx draws attention in the third volume–common to exchangeable goods?

Why then, I ask again to-day, may not the principle of value reside in any one of these common properties as well as in the property of being products of labour? For in support of this latter proposition Marx has not adduced a shred of positive evidence. His sole argument is the negative one, that the value in use, from which we have happily abstracted, is not the principle of exchange value. But does not this negative argument apply equally to all the other common properties overlooked by Marx? (Bohm-Bawerk, Karl Marx and the Close of his System, Ch. 4)

Bohm-Bawerk accuses Marx of failing to consider the following options:

Scarcity in proportion to demand

Subjects of demand and supply

Appropriated objects

Natural products (the labor process always combining labor with natural materials)

Causes of expense for producers

Certainly we could make the list even longer if we wanted. We could add that all commodities are subject to the law of gravity, or that they are in orbit around the sun. But we do not need to be uncharitable. Bohm-Bawerk of course does not mean that every possible common factor is equally likely. Instead he is listing alternatives he finds to be at least equal probable, if not more probable, than labor.

Still, some of these answers clearly don’t work. For example, saying that something is subject to demand and supply is to simply say it is an exchange-value. It tells us nothing about what the equal common factor is that exchange values are expressing.

Others could easily be made consistent with Marx’s law of value too. What is the expense suffered by the producers other than their labor? Isn’t labor the truly scarce factor?

But these points aren’t worth pursuing further because Bohm-Bawerk is making a more fundamental error in his interpretation of Marx.

Marx was not saying that commodity exchange arises because of a common factor they all share. Rather, he is saying that, in exchange, labor is the common property regulating the terms of the trade.

Bohm-Bawerk is getting Marx wrong because he reads Marx’s argument as formalist, deriving his ideas from the formal and ahistorical concept of exchange. He is rather looking at the specific kind of exchange taking place in capitalism. This point is addressed more in the next section.

(Note: I think Kay could and should have expanded more here too. Why does he suggest that labor is the only truly scarce factor? Labor alone cannot create, and the idea that it can is a bourgeois lie Marx emphasizes at the start of his Critique of the Gotha Programme. There are things scarce other than labor-power, and their use is a kind of expense too. Kay’s refutations aren’t too informative of exactly how he is responding to Bohm-Bawerk here, but he says as much because he thinks the refutation of Bohm-Bawerk’s third attack is useful for understanding the problems with the second.)

Can Marx’s logic be used to defend use-value as the common factor?

A purely logical proof of value?

Bohm-Bawerk’s first two attacks focused around errors Marx is meant to have made in how he set up his ‘negative’ argument. The first argues that Marx wrongly listed labor as a common property only because he limited our focus to commodities, not all exchangeable goods. The second argues that Marx wrongly omitted other common properties that Marx did not eliminate.

The third attack consider Marx’s argument itself, namely in how he eliminates use-value as the common factor being expressed as exchange-value. Bohm-Bawerk believes that the same argument Marx presents against use-value and in favor of labor could be entirely turned on its head so that it argues against labor and in favor of use-value.

If Marx had chanced to reverse the order of the examination, the same reasoning which led to the exclusion of the value in use would have excluded labour; and then the reasoning which resulted in the crowning of labour might have led him to declare the value in use to be the only property left, and therefore to be the sought-for common property, and value to be "the cellular tissue of value in use." (Bohm-Bawerk, Karl Marx and the Close of his System, Ch. 4)

We saw before how Bohm-Bawerk described Marx’s method as “a purely logical proof, a dialectic deduction from the very nature of exchange.” However, these are not the same thing. In fact, the represent two very different ways of doing things. A “purely logical proof” abstracts away from all phenomenon, while dialectical deductions directly engages with it.

When Bohm-Bawerk accuses Marx of making a purely logical proof, he understands him as arguing something like this:

Imagine a population P consisting of individuals who all share the properties A and B. While A and B are present in every member of P, the specific form it takes varies for every member as well. Thus A presents itself as a’, a’’, etc., while B presents itself as b’, b’’, etc.

In this kind of case, we clearly could not claim that B is the only common property shared in P just because A only presents itself as a’, a’’, etc., as the exact same thing is true of B.

Bohm-Bawerk thinks this is exactly what Marx did. Bohm-Bawerk saw Marx’s problem as a logical one, where ‘labor’ and ‘use-value’ were mere names being given to A and B. If Marx can accept that commodities might embody ‘abstract labor’ despite the wide variety in different kinds of concrete labors, then there is no reason why he could not also do the same thing for use-values. While each commodity has a different use-value, we might say they all have ‘abstract usefulness.’

Formalist vs Dialectic Looks at Use-Value and Labor

This kind of formalist approach fits with the neo-classical school Bohm-Bawerk represents, treating logic as something that exists purely in the mind and outside of the object being studied. But this method does not line up with the dialectical method, which is never purely formalist, never entirely divorced from the subject it is analyzing.

When Marx is saying that concrete labor is reduced to abstract labor, but that use-value only exists in particular forms, he is making a claim about the nature of labor and use-value. Likewise, Marx was not reasoning from the formal concept of exchange to his conclusions, but was trying to study the basis of exchange as it exists specifically within capitalism.

Why can’t we move from a particular use-value to use-values in general? What is so objectionable about the idea of ‘general utility’? Marx gives this answer:

The utility of a thing makes it a use value. But this utility is not a thing of air. Being limited by the physical properties of the commodity, it has no existence apart from that commodity. A commodity, such as iron, corn, or a diamond, is therefore, so far as it is a material thing, a use value, something useful. (Marx, Capital, Vol. 1, Ch. 1)

In other words, the idea of something having ‘utility’ only makes sense when we are considering a particular material form. As something general, it has no existence.

Marx is following Hegel, having something only being ‘real’ when it is embodied. Use-value in general can only exist in the mind of the economist. Bohm-Bawerk does not understand this objection because he thinks Marx is objecting on logical grounds, but that its existence cannot be separated from the particular physical properties of the commodity.

The obvious follow-up to this is, if it is impossible for use-value in general to exist this way, why should we expect anything different for labor? Bohm-Bawerk, in a slightly different context, asks exactly this question:

If we look at this dispassionately, however, it fits still worse, for in sculpture there is no "unskilled labour" at all embodied, much less therefore unskilled labour equal to the amount in the five days' labour of the stone-breaker. The plain truth is that the two products embody different kinds of labour in different amounts, and every unprejudiced person will admit that this means a state of things exactly contrary to the conditions which Marx demands and must affirm, viz., that they embody labour of the same kind and of the same amount! (Bohm-Bawerk, Karl Marx and the Close of his System, Ch. 4)

Qualitatively, it is certainly true that different products embody different kinds of labor. Labor always takes the form of concrete labor, being a particular kind of task (sculpting, tailoring, weaving, etc.). It therefore seems like the idea of ‘abstract labor’ would have no more legitimacy than the idea of ‘use-value in general.’

It is certainly true that the way Marx deals with this isn’t satisfactory. He often treats ‘abstract labor’ like it is just referring to the common features of all labor. This wouldn’t meaningfully distinguish it from the category of use-value in general. Marx opens himself up for Bohm-Bawerk’s criticism.

For example, consider when Marx says this:

On the one hand all labour is, speaking physiologically, an expenditure of human labour power, and in its character of identical abstract human labour, it creates and forms the value of commodities. (Marx, Capital, Vol. 1, Ch. 1)

If all Marx were doing here were saying that all labor has certain physiological similarities, then Bohm-Bawerk could reply that all use-values have psychological similarities. One is just as valid as the other.

Or consider when Marx says this:

This abstraction, human labour in general, exists in the form of average labour which, in a given society, the average person can perform, productive expenditure of a certain amount of human muscles, nerves, brain, etc. (Marx, Critique of Political Economy, Ch. 1)

Marx’s method here seems quite like the method Bohm-Bawerk is using. Marx certainly isn’t being dialectical here, as he is just constructing a purely mental abstraction.

Compare this to how we classify dogs and cats as mammals. This can certainly be a useful for science to no longer see these things as entirely separate, but no scientist has ever examined ‘the mammal.’ It’s purely a category of classification.

Likewise, if abstract labor is just the expenditure of brain, muscle, etc., the common properties of labor, we aren’t getting to the real content Marx was after. Just as exchange-value is the form of appearance of value, something real and distinct from it, concrete labor is the form of appearance of abstract labor. If abstract labor were just the common properties of concrete labor, it would not be distinguishable at all. It’s just a move from the specific form to the genus.

Furthermore, this approach also dehistoricizes Marx’s categories. If abstract labor is just the common properties of concrete labor, then it must exist in all periods of human history. But if abstract labor is universally present, then so will its product “value” be. We are therefore no longer looking at the specific historical form of commodity production.

How Labor is Equated in Commodity Exchange

Despite these odd comments, abstract labor is not just the common properties of concrete labor, nor is concrete labor the mode of existence of abstract labor. If we look at Marx’s work as a whole instead of just these passages, this becomes clear.

Part of the issue here comes from the term ‘abstract.’ Kay prefers Marx’s alternative name of ‘social labor,’ which is not as ambiguous. It is hard to see how abstract labor is the inner essence of concrete labor, but it is less hard to see how social labor is essential to individual labor.

We can easily see how the work done by a specific person is simultaneously the work of particular worker while also being an organic part of the labor of all society, and also derives part of its significance from that fact. This shifts the focus from muscles and brains to how the work of an individual is part of the labor of society, no matter how different its particular content might be.

Consider an exchange between two individuals. Following Marx’s example, they are a tailor and a weaver trading a coat for 20 yards of linen. In both cases, their labor is concrete as tailoring and weaving. But when exchanged, they gain a different use-value. They learn, in a very practical way, that their particular type of labor can gain the product of any other kind of labor. Thanks to exchange, the tailor can, through their tailoring, gain the product of weaving. As Marx puts it, they learn that

[O]ne use value is just as good as another, provided only it be present in sufficient quantity. (Marx, Capital, Vol. 1, Ch. 1)

Any one type of labor embodied in a commodity becomes the equivalent of every other kind of labor embodied in commodities, no matter how different.

Abstract or social labor isn’t just about ignoring the differences between the many types of concrete labor. It is actually the differences between these types of labor that leads to the need for abstract labor. With the development of the division of labor and the subsequent need for commodity exchange, individual labor increasingly ceases to be purely individual and becomes more an aspect of social labor. Labor remains specific, but can less and less exist in isolation.

Bohm-Bawerk’s objection that the existence of different types of labor, particularly about the difference between skilled and unskilled labor, excludes the possibility of abstract labor, is superseded. Marx wasn’t ignoring the differences between the types of labor. On the contrary, their difference is the reason abstract labor develops.

(Note: Elson’s view of abstract labor differs from Kay’s view significantly here, and I think some weaknesses of Kay’s argument highlight why Elson’s argument is better. Elson argues that, in Marx’s view at least, something can be a ‘valid abstraction’ even when lacking a ‘practical truth.’ Consequently, she has no issue with accepting that abstract labor exists in all epochs of history, nor does this commit her to the position that value must exist in all epochs.

Kay does not seem to have accepted this, which explains why he reacts so negatively to Marx’s description of abstract labor in general terms like ‘expenditures of human labor-power’ or thinks that if abstract labor exists then so too must value. Yet when it comes to laying out his own position, he conflates abstract labor with social labor, but his description of social labor also clearly applies in all epochs, even if not to the same degree of importance, and certainly would continue to exist in any socialist economy. He presents abstract labor as the efforts of an individual when viewed as part of this collective effort.

However, we might ask that, if we are accepting things without a ‘practical truth’ as a ‘valid abstraction,’ then why can’t we accept use-value in general? I tend to think use-values must be a valid abstraction or else we wouldn’t have the category of ‘use-value’ in the first place. Marx presents a ‘rational abstraction’ as something that brings out and fixes a common element to save from reputation. Categories like ‘use-value’ or ‘mammal’ does this. The issue with treating use-values the same way we do abstract labor is not because we cannot make a rational abstraction of it. We can find common features of all use-values, namely that they satisfy some want, but this does not imply that all wants can be reduced to a ‘general utility’ or cardinally measured in ‘utils’. The bigger issues, as Elson also seems to highlight, is that it is precisely the differences, not the equality, between use-values which is highlighted by exchange, there being no common ‘want’ underlying our particular wants are merely sharing in and contributing to, and that utility seems to be mainly a subjective feature held by individuals whereas we need to explain a system were exchange-ratios are appearing as given, set ‘behind the backs’ or the producers.)

How Abstract Labor is Embodied

But a problem remains: if concrete labor is not the form of existence for abstract labor, then what is? To have any existence outside of our minds, it must be embodied in some way. This is what Marx addresses in the third section of the first chapter of Capital, focused on the Value-Form or Exchange-Value.

Labor becomes abstract when embodied in a commodity, constituting its value. To find how it is embodied, we are looking for the value-form. In an elementary exchange of two commodities, the value of one is expressed in terms of the quantity of another. In Marx’s example, where 20 yards of linen exchange for a coat, the coat becomes the form of existence of the linen.

The first peculiarity that strikes us, in considering the form of the equivalent, is this: use value becomes the form of manifestation, the phenomenal form of its opposite, value. (Marx, Capital, Vol. 1, Ch. 1)

In other words, when an individual exchanges one commodity for another, the labor put into one commodity is represented directly and actually in the use-value they acquire.

In order to express the value of the linen as a congelation of human labour, that value must be expressed as having objective existence, as being a something materially different from the linen itself, and yet a something common to the linen and all other commodities.

[…]

As a use value, the linen is something palpably different from the coat; as value, it is the same as the coat, and now has the appearance of a coat. Thus the linen acquires a value form different from its physical form. (Marx, Capital, Vol. 1, Ch. 1)

When a commodity represents the value of another, Marx calls it the ‘equivalent form of value.’ In a simple exchange, one commodity provides this for another. But when exchange becomes more systematic, a single and universal equivalent develops: money.

As the universal equivalent, money shows not only that all commodities in fact have this common property, but acts as that common property. It is the means through which the embodiment of every individual concrete labor can be transformed into that of any and every other type of concrete labor. It is the medium through which concrete labor becomes abstract labor.

Money is the form of existence for abstract labor.

Quantity and Quality

We have seen that Bohm-Bawerk’s critique of Marx’s theory of value falls through. However, we don’t have any explanation yet for the apparent contradiction between Volumes 1 and 3.

Bohm-Bawerk believed Marx theory of value, if it meant anything at all, meant that the price of commodities are proportionate to their value. Any systematic deviation from their value, as seen in Volume 3, would therefore be a contradiction.

There are two aspects to Bohm-Bawerk’s criticism. Firstly, there is the quantitative relation between value and the price of production. Secondly, the relation between quantity and quality.

The first issue seems to be more simply solved. Bohm-Bawerk held Marx to say that the magnitude of value alone determines prices, when really it is the magnitude and composition of value that determines it. This is perfectly in line with the claim that prices are being determined by values.

The second issue is more fundament, highlighting differences between Marx and bourgeois economists again. The positivist method of the bourgeois economists relied on contentless abstractions, using their formalist approach. They cannot move from the abstract to the concrete through a series of specifications and mediations. Instead, they need to grasp reality directly and immediately.

Bohm-Bawerk attempts to do this. He proposed a theory of value based on this intangible idea of general utility and tried to immediately explain prices. For him, a theory must explain the magnitude of value at the same time it explains its nature.

In contrast to some modern economists, Bohm-Bawerk did not think value theory was a ‘great fuss about nothing.’ He recognized that economic magnitudes could not be explained in terms of each other. He accepted the need for a theory of value, although only insofar as it works as an immediate and direct explanation of prices.

In Capital he therefore took it for granted that, if the value of a commodity is determined by the amount of socially necessary labor it needs, then commodities would actually exchange for each other in practice in ratios that are perfectly proportionate to their value. If we approach Capital with this kind of neo-classical economic mindset, we can seem to find support for this reading as well.

If it were only Bohm-Bawerk and other economists who read Marx this way, this all wouldn’t be that much of a problem. However, similar interpretations frequently show up among Marxists as well. Hilferding played with this idea in his own response to Bohm-Bawerk:

If Marx had really maintained that, apart from irregular oscillations, commodities could only be exchanged one for another because equivalent quantities of labor are incorporated in them, or only in the ratios corresponding to the amounts of labor incorporated in them, Böhm-Bawerk would be perfectly right. But in the first volume Marx is only discussing exchange relationships as they manifest themselves when commodities are exchanged for their values; and solely on this supposition do the commodities embody equivalent quantities of labor. But exchange for their values is not a condition of exchange in general, even though, under certain specific historical conditions, exchange for corresponding values is indispensable, if these historical conditions are to be perpetually reproduced by the mechanism of social life.

[…]

We thus see that the Marxist law of value is not canceled by the data of the third volume, but is merely modified in a definite way. (Hilferding, Bohm-Bawerk’s Criticism of Marx, Ch. 2)

In these passages, Hilferding gives the impression that the move away from equal exchange is a move from the norm.

Today we find Michio Morishima and George Catephores arguing that the conditions for equal exchange never existed historically, denying any ‘simple commodity production’ society. But their commitment to the idea is strong enough that they bring it back immediately as a ‘logical simulation.’

This move to logical simulation represents a fall to positivism, using equal exchange as an ‘analytical device.’ Funnily enough, both Engels and Bohm-Bawerk seem to have criticized Werner Sombart for having interpreted value as merely a tool of logic this way.

All this goes to show there is a continued fascination of Marxists with the idea of equal exchange. They either treat it as a real process that really existed in some set of historical conditions, or they treat it purely as a model. Both approaches have problems since no such historical circumstance ever existed and the second requires positivism.

We are therefore led to what seems like a surprising conclusion: equal exchange plays no fundamental part of Marxism. Marx might have used the idea at times for simplicity or to explain something, but no substantial part of his theory relied on it.

This can be demonstrated through two vital points. Firstly it can be seen in how exactly value is established as a category. Secondly, it can be seen in Marx’s theory of surplus-value.

The Establishment of Value as a Category

Marx’s logic at the start of Capital Volume 1 does seem to work from an assumption of equal exchange.

Therefore, first: the valid exchange values of a given commodity express something equal; secondly, exchange value, generally, is only the mode of expression, the phenomenal form, of something contained in it, yet distinguishable from it.

Let us take two commodities, e.g., corn and iron. The proportions in which they are exchangeable, whatever those proportions may be, can always be represented by an equation in which a given quantity of corn is equated to some quantity of iron: e.g., 1 quarter corn = x cwt. iron. What does this equation tell us? It tells us that in two different things – in 1 quarter of corn and x cwt. of iron, there exists in equal quantities something common to both. (Marx, Capital, Vol. 1, Ch. 1)

It is remarks like this that give the impression that Marx was making substantial use of the idea of equal exchange or simple commodity production.

In context however, we can see that equal exchange is not necessary at all. The conclusion Marx works to here, i.e. the idea that the only common properties of commodities is that they are use-values and they are products of labor, does not depend on equal exchange.

Suppose that two times the amount of labor is needed to harvest corn than to smelt iron, meaning the corn has double the value of the iron. An exchange of these commodities still brings two different things face to face. There will be, to paraphrase Marx, something common to both, yet here not necessarily in equal amounts.

The position advanced by Marx is that exchange reveals different use-values to share a common property as products of labor, but not on the idea that only commodities with equal amounts of labor may exchange.

Consider the exchange 1 quarter of corn = 1/4 cwt. of iron. Here the iron takes the place of the equivalent form of value. The use-value of the iron represents the value of the corn.

It is true that only a commodity that is itself a value may act as an equivalent. But once it is in that position, it is its use-value that is is representing the value of the relative form. This leads to the possibility that there may be an incongruity between the value that the equivalent is representing and its own value.

This incongruity is an essential feature of Marx’s analysis of money. We can therefore see that far from the law of value resenting on equal exchange, it is actually presupposing unequal exchange.

Bohm-Bawerk had confused, as Hilfdering pointed out, value with price. Marx’s actual position is that commodities are alike in that they are products of labor, and that this becomes apparent and real (gaining a practical truth) through the process of systematic exchange. Marx was not beginning Capital with a theory about the rates commodities exchange for one another. Instead, he was studying the nature of value as a quality. The move of his analysis from quality to quantity requires a few more stages of mediation.

But positivist though, whether found in neo-classicalism or even in Marxism, disregards this progress, trying to leap directly from quality to quantity. In its modern vulgar form this is ignored all together.

Bohm-Bawerk’s critique collapses on this point which actually represents a greater methodological weakness of neo-classical economics in general.

(Note: The argument that Marx was focused on the quality of value is a strong point here, and fits with what actually seems to be the point of Marx’s argument, as is the point that it is the use-value, not the value itself, of the equivalent form that reflects the value of the relative form. This does open up a clear way we can see an incongruity between value and price. However, Kay is not elaborating much here on why Marx is saying that in this equation we are meant to see something that exists “in equal quantities.” If Marx were only making a point about a common quality, he could and should have left that out. Here I find Elson’s explanation better, that Marx is emphasizing that exchange really does appear to be reflecting the magnitude of value, and Marx has not, at the start of Capital, presented any reason to challenge this appearance. Marx has assumed away the social relations which would imply this is not possible until Volume 3, where he considers the distribution of value between capitals. While we begin by viewing commodities as products of labor, we later see they are products of capital, meaning their value also contains surplus-value. This forces us to reexamine how magnitudes of value are being represented by prices.)

Quantity and Quality in the Theory of Surplus Value

The relationship between the economic form (quality) and their magnitude (quantity) is just as important in the theory of surplus-value.

Bohm-Bawerk only deals with this in passing though, seemingly because he conceded that the ‘middle’ part of Marx’s system was quite consistent. This hints at how Bohm-Bawerk might have tried to criticize the theory of surplus value if he thought it necessary.

Bohm-Bawerk would have had no doubt that labor-power is a commodity which, like others, is exchanged at its value. But if we remove this false premise then the theory of surplus-value falls apart. If wages are no longer tied to the value of labor-power, then the rate of surplus-value becomes completely indeterminate. In fact, even the existence of surplus-value is called into question.

Surplus-value is basically a quantitative phenomenon. It is the difference in the magnitude of the value produced by labor-power and the value of labor-power itself. Marx is taking it for granted that the difference between these two is positive, but this cannot simply be assumed. For capital to consistently get surplus-value and profit, then wages need to be consistently less than the value labor-power produces.

This is possible only when wages equal the value of labor-power. Yet we have dropped the need for equal exchange. We can reconstruct what an answer from Bohm-Bawerk might have looked like:

In this case, as in many others, he manages to glide with dialectic skill over the difficult points of his argument. He introduces equal exchange, but not for what is is, the only and necessary support for his argument, but as a virtue, as though it were a difficulty for him to overcome.

Our friend, Moneybags, who as yet is only an embryo capitalist, must buy his commodities at their value, must sell them at their value, and yet at the end of the process must withdraw more value from circulation than he threw into it at starting. (Marx, Capital, Vol. 1, Ch. 5)

In Value, Price and Profit he sets himself the same difficult problem.

To explain, therefore, the general nature of profits, you must start from the theorem that, on an average, commodities are sold at their real values, and that profits are derived from selling them at their values, that is, in proportion to the quantity of labour realized in them. If you cannot explain profit upon this supposition, you cannot explain it at all. (Marx, Value, Price and Profit, Ch. 6)

Bohm-Bawerk could have concluded that surplus value being consistently positive depends on the idea of equal exchange for the commodity of labor-power. Thus if we are dropping the idea that commodities must exchange at their value, then we also drop Marx’s entire theory of surplus-value.

It is true enough that the existence of surplus-value does involve a tendency for labor-power to exchange at its value. But the connection between the value of the wage and surplus-value is the opposite of this kind of positivist approach we are imagining Bohm-Bawerk might have argued.

Marx is not arguing for the existence of surplus-value based on the idea that wages tend to equal the value of labor-power. Rather, he is arguing from the existence of surplus-value to this tendency.

Marx arrives at the concept of surplus-value in chapter 4 of Capital, well before he focused on the buying and selling of labor-power in chapter 6. Without going over all of these chapters, his logic follows this pattern.

In the systematic exchange of commodities, value finds a form of social existence in the use-value of one commodity turned into the universal equivalent, i.e. money. This money commodity starts like any other commodity, but its role as universal equivalent is socially established. It separates itself off from other commodities this way.

This way, even its own particular use-value drops into the background, and it exists more exclusively as the form of value of all other commodities. This is the point where we see the transformation from quality into quantity. As value, commodities are indistinguishable from one another except in their size. Money, the value-form, confirms this as sums differ only in terms of quantity.

In the simple circulation of commodities, C - M - C (commodity sold for money which is then used to buy another commodity), money acts merely as a medium of exchange. Money’s existence as capital remains latent. It appears when we move to the circulation of value, M - C - M’ (money buys commodities that, thanks to exploitation, produces something that can be sold for money than was started with).

The reason for the circulation of value is surplus-value, changing one sum of money M into the larger sum M’.

When we start to consider labor-power, we need to analyze it in the context of this already established circulation. But we know labor-power is a special commodity since its use-value is to produce value, including surplus-value.

If capital is going to appropriate the surplus-value of society, then wages must be below the value that labor produces.

At the same time, the purely quantitative nature of value means that the appropriation of surplus value is also the tendency for maximum surplus value. Capital is therefore driven to lower wages not only to a value below what labor will produce, but to the lowest possible level, i.e. the value of labor-power.

The magnitude of wages, and with it the rate of surplus-value, follows from the nature of surplus-value as a category. This is a clear subordination of quantity to quality.

Conclusion

Bohm-Bawerk’s critique of Marx does not have a single point of validity. Marxists need not concede anything to him. However, understanding why we don’t need to is incredibly useful, making his critique quite valuable. By refuting it, we gain a better understanding of the fundamentals of Marxism.

Karl Marx and the Close of his System is the most substantive criticism any bourgeois economist have made against Capital. It has inspired all other criticisms. It also puts all of neo-classical economic theory on the line, since it also reveals the fundamentals of that system and why it is faulty.

We therefore turn the ‘Russian retreat’ of Marxism into the ‘Waterloo’ of neo-classicalism. However, neo-classical economic has not disappeared. Even worse, these positivist ideas have had a damaging effect on Marxism from within.

Readings of Bohm-Bawerk’s work will only be valuable if it is read with these points in mind.