Diane Elson's "The Value Theory of Labour" in Plain(er) Language

Thoughts on Elson’s Paper

Diane Elson’s essay “The Value Theory of Labour” (1979) is perhaps one of the best essays on Marx’s value theory I’ve seen, and an important correction to those who dismiss, or defend, Marx as supporting a “labor theory of value.” The term “value theory of labor” was previously used by Raya Dunayevskaya in her essay “The Logic and Scope of Capital, Volumes II and III”.

There are a few points that I would like to have seen expanded on, especially related to the move from gold money to paper money. Some more direct addresses to the critiques of Böhm-Bawerk might have also been nice, although this essay was published alongside another essay by Geoffrey Kay “Why Labour is the Starting Point of Capital” which Elson directs people to more directly, although also notes a few times she disagrees with Kay as well in how he presents abstract labor.

The full collection of essays can be found in “Value: The Representation of Labour in Capitalism”. The essay itself should be understood in the context of debates in the Conference of Socialist Economists (CSE), as Elson spends much of her time correcting often subtle errors in their interpretation of Marx.

Often when I read complicated works, my notes end up being me rereading over certain lines enough until I can explain it back to myself in a way more like my own words. I have done that here with limited success. This is easier for me to go through, but especially as a paper trying to explain Marx’s own argument and jargon, it will often be pulled back in. A full ‘plain language’ explanation would need to pass through this a few times and probably be less focused on responding to other individual economists.

I have also titled these sections largely in ways in line with Elson, but combined some sections where the point needed was brief, and added in other section titles for parts that were relatively long.

I also recommend checking out Mike Gouldhawke’s essay “The Labour-Power Theory of Capital”.

Since this page has become more like my own note-taking process, I will begin here by trying to summarize the major points, coming back to the ‘plain language’ explanation. My more detailed notes/restatement/rewriting will come after this ‘summary’ section.

The Brief Summary of Elson’s Paper

What is Marx’s Theory of Value a Theory Of?

1. The Theory of Value: A Proof of Exploitation?

Elson begins by discussing the object of Marx’s theory of value.

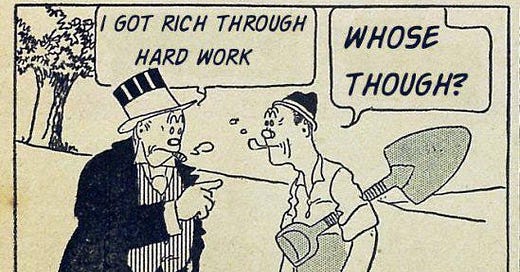

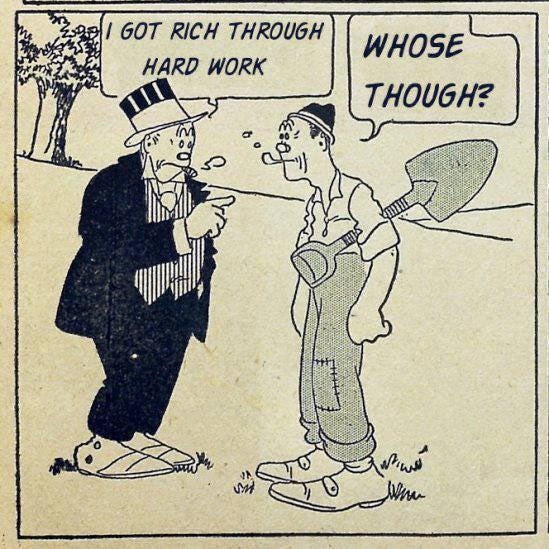

Marx is commonly interpreted in two ways. The first theory claims that Marx’s value theory is meant to act as proof that workers are being exploited in capitalism. The second theory claims Marx’s value theory is meant to work as an explanation of prices in capitalism, as a “labor theory of value” (LTV).

Elson disagrees with both of these positions.

We know the first theory is wrong because Marx recognized pre-capitalist societies, like feudalism, as exploitative while recognizing his value theory as specific to capitalism. The method we use to determine whether exploitation occurs is therefore distinct from the theory of value, which is a theory meant to specifically apply to capitalism. It follows that he is using some other method for determining whether a society is exploiting workers. Specifically, Marx looked at whether some group of society has monopolized the means of production and is therefore able to make others do surplus-labor.

2. The Theory of Value: An Explanation of Prices?

The second theory, the LTV interpretation, is a bit more complex, especially since it is a much more common interpretation of Marx. It is often used as a way to compare Marx to other “value theorists” like Adam Smith, David Ricardo, etc., and turns this into an empirical question over whose theory models prices best.

According to the LTV, the equilibrium price of commodities in the market tends toward the amount of labor needed to make it. If it’s harder to make something, requiring more labor, it is more valuable and has a higher price. If it becomes easier to make, requiring less labor, it is less valuable and becomes cheaper.

Two arguments are given for the LTV. The first is Adam Smith’s “deer and beaver” argument, which basically says that people naturally tend to direct their labor to where it is more rewarded. The second argument is a little more complex, saying that a society in certain conditions will produce some mass of products, part of which will go to the workers and part which is a surplus which becomes profit. The size of this surplus is measured in labor-time, setting the aggregate level of profit for the entire economy which is then distributed across various industries, and therefore sets prices along with it.

Both of these arguments treat labor-time as an independent variable found in production which then determines prices as the dependent variable. It treats production and circulation as distinct processes, even if connected. It also tends to depoliticize Marx’s theory, turning Marx into merely a proto-mathematical economist.

There are also serious empirical issues with any LTV theory making it redundant at best. Elson has no intention of rescuing any “labor theory of value.”

3. An Abstract Labour Theory of Value?

LTV theorists cannot save their theory simply by emphasizing that Marx was using ‘abstract labor.’ While this is an important distinction Marx made, but doesn’t seem to help address the objections to the LTV.

Elson denies that Marx was trying to develop a theory of prices at all. Marx wasn’t looking at prices as ‘values’ and finding the answer in labor-time. He was looking at how labor is represented in capitalism and finding it to be value, as well as considering the political implications that come from this. He had a value theory of labor.

4. Labour as the Object of Marx’s Theory of Value

Marx said he began Capital with an examination of the commodity because it is the “simplest form in which the labour product is represented in contemporary society.” This seems to confirm that labor was his real object. It also helps to address some critiques, like from Böhm-Bawerk, that claim Marx was ‘cheating’ by only considering the price of things made by labor and leaving out how some things have prices without being products of labor, like the price of untouched land.

5. A Possible Misconception: The Social Distribution of Labour

Even if we say Marx was focused on labor, some people might also misread this as Marx focusing on the distribution of labor, as if we were dealing with a pre-given economic structure with a bunch of tasks that need to be done which labor is being spread out through. This interpretation of Marx can be found in a few places, but tends to just reduce back down to an LTV, albeit one that focuses on value more in the process of circulation instead of in production.

6. The Indeterminateness of Human Labour

Marx didn’t hold to this kind of ‘pre-given’ structure view. Instead, he focused on labor as a dynamic and living force, something highly adaptable and full of potential. Any society then, including capitalism, needs some system to ‘fix’ this fluidity, directing labor by particular people toward particular goods to be made in a particular way. The potential is actualized by some process. This is how labor is ‘determined.’

To say labor is being ‘determined’ here is not meant in a ‘deterministic’ way. He isn’t denying a role of individual choice. But whatever choices we make are limited within whatever context we find ourselves in.

Misplaced Concreteness and Marx’s Method of Abstraction

Elson moves on from the object of Marx’s theory to Marx’s method of abstraction.

1. Rationalist Concepts of Determination

Elson contrasts Marx’s method with ‘rationalist’ concepts of determination. These theories have a ‘misplaced concreteness’ where they understand things in terms of relations between independent and dependent variables which are discretely distinct from one another. The labor theory of value is an example of one such way of looking at things.

2. Determination in Marx’s Theory of Value: The Relation Between Labour-Time, Value and Exchange-Value

Marx’s idea of determination is different, where the thing doing the ‘determining’ is also a part of what is being determined. There is both a continuity and a difference between these elements, rather than them being discretely distinct from one another.

Going into Marx’s value theory, we see this in his idea that value is determined by ‘socially necessary labor time’ or by ‘abstract labor.’ Production in any society will take some set amount of time, but it is only in capitalism that Marx thinks this labor-time is being turned into value. Value isn’t the same as abstract labor, but it isn’t entirely distinct either. Value is a particular form that abstract labor is taking. There is both a continuity and a difference. This is especially emphasized by Marx’s chemical and biological metaphors as things crystalize, become embodied, go through a metamorphosis, etc.

Marx sees the relation between value and exchange-value to be similar, despite how different they seem. Marx claims that, without exchange-value, value would have no ‘practical reality.’ If we are going to really attribute value to commodities, then this needs to be connected to some immediately obvious appearance of the commodity, even if this appearance doesn’t immediately inform us about the true nature lying underneath.

Value needs exchange-value as a way to express itself. This is something it will ultimately only be able to do when something (money) is able to act as a universal equivalent, allowing all products of labor to be compared.

We can again contrast this to the labor theory of value. There we were supposed to be able to determine, at least in principle, the value of a commodity completely independently from prices. They were discretely distinct variables. But here they are mixed up together, and cannot be cleanly separated.

3. The Measure of Value: Labour-Time and Money

Marx did not think that the value of a commodity could be measured apart from its price. Even if labor-time is what determines value, we cannot just find the average amount of time it takes to make something and declare that to be its value. Why? Because we only ever observe concrete labor as it is carried on by specific individuals. What matters for value though is social and abstract labor, and these aspects only become obvious in exchange.

Why is Marx saying that both labor-time and price are working as measures of value, especially if he isn’t using this kind of relation of independent and dependent variables? The idea seems to come down to Marx’s notion of immanent and external measures. An internal measure is the feature of something that allows it to be measured in terms of quantity. The external measure is the medium actually used to measure something.

For example, we can use iron to measure the weight of something on a balance scale, but that only works with things that actually have weight. Iron here works as an external measure of weight, but that is only possible thanks to the ‘immanent’ measure of something actually having weight.

Abstract or ‘indifferent’ labor-time works for Marx as the immanent measure of value. Hours of labor can be added or subtracted from one another, allowing for it to be cardinally measured. This can only be done when we consider labor as an expenditure of labor-power in general, as something that takes time and effort. The same could not be said for concrete labor, since we can’t exactly add one hour of weaving to one hour of tailoring.

4. The Analysis of Form Determination: The Method of Historical Materialism

The method Marx is using in all this is ‘historical materialism.’ This is a way of looking at how social forms are determined through a historical process. These forms dissolve, change, and develop into new forms according to their own internal dynamics over time. These forms are both determinate and transient. This, again, contrasts with the rationalist view of determination, which is a much more static relation, and any change represents a sudden discontinuity.

The method of historical materialism begins with a phase of analysis where we look at some historic form as being made up of opposed “potentia.” These aspects co-exist within the form and work as parts of functions in process. This is generally what Marx means when he talks about ‘contradiction.’ The example of elliptical motion, as something simultaneously moving away and toward a body, is a good illustration of this. These counter-posed aspects work as ‘determinants’ for Marx. They act as one-sided abstractions being singled out from a form.

The phase of analysis is followed by a phase of synthesis. After we’ve broken down a form to the potentia which make it up, we build things back up to the appearance we began with, now with a greater understanding of how it works. This builds our understanding of the form we are studying, suggesting new aspects of it that can then be analyzed, repeating the process over again and deepening our understanding each time.

There is a danger here that, in the process of analyzing a one-sided abstraction, we give this abstraction the appearance of begin its own self-developing entity. This is the trap Marx believes Hegel fell for. However, just because Marx recognizes this risk himself doesn’t mean he also didn’t fall for it, which would be the case if we start treating value like its own self-developing and independent entity too. Elson believes Marx does not make this kind of mistake and, in elaborating his theory, wants to defend him from this critique.

Marx’s Value Theory of Labour

1. Aspects of Labour: Social and Private, Abstract and Concrete

We move on from Marx’s method to his actual value theory of labor.

We begin by considering the various aspects of labor. Marx divided labor into four aspects, presented in two opposing pairs: abstract labor and concrete labor, and social labor and private labor.

Elson argues that these aspects are common to all labor, rather than being certain types of labor. They are one-sided abstractions of the whole of living labor.

She also argues they are also common to all epochs of history. This is a more controversial view on her part since many Marxists argue that abstract labor only exists within capitalism, presumably because they closely associate it with value. But since Elson thinks value is only one form abstract labor is taking, she has no issue calling it a valid abstraction even in societies where it does not take on this kind of ‘practical truth’ as value.

Elson also holds that, while there is some overlap between these aspects of labor, they are really distinct.

In capitalism, commodities are the products of private labor, which seem to only gain their social form in exchange. But in truth the labor was social from the beginning, even if only in a latent form that is being realized in exchange.

There is some overlap between the idea of private labor and concrete labor. Both focus on the individual and the subjective aspects of their labor. But concrete labor adds to this an idea of a process going on between man and nature, with this private labor being a specific kind of process like tailoring, weaving, spinning, etc. Concrete labor presents labor as diverse and heterogenous.

But the various kinds of labor also share some common characteristics. All labor takes time and effort, irrespective of what kind of labor it is. This is the abstract aspect of labor, considered only as homogenous human labor distinguished from one another only by the quantity of their duration.

This idea of abstract labor also overlaps with social labor, as both are looking at labor in a way detached from specific individuals. This is viewing labor as some fraction of the collective effort humanity is doing. But abstract labor adds on this idea of quantity not seen in social labor.

In capitalism, the abstract aspect of labor is dominant, making the other aspects subject to it. The social aspect of labor is only seen in exchange for money, which we will see is acting as the universal equivalent and the incarnation of abstract labor. The concrete and private aspects of labor also need to be mediated by this abstract aspect, satisfying someone’s individual needs only when their product is transformed through exchange for what they want.

This domination of abstract labor over the other aspects signifies that capitalism is a system of production dominating mankind. The process of production has mastery over mankind instead of the other way around.

Given this, we can also see why it is wrong to think that abstract labor is unique to capitalism. It is gaining a particular kind of ‘practical truth’ and stands out as especially important in capitalism. In capitalism, abstract labor is objectified, and this is reflected in exchange-value. This is why Marx begins his analysis with a study of the commodity, the simplest social form that the product of labor presents itself as within capitalism.

2. The Phase of Analysis: From the Commodity to Value

Having noted how Marx will be thinking about the various aspects of labor, we move on to his actual argument for why we should think all of this is actually the case in capitalism.

Marx begins with the commodity, as we said, as the simplest social form the product of labor presents itself as in capitalism. He analyzes the commodity dialectically, first considering as made up of two opposed aspects: use-value and exchange-value. Since exchange-value is the aspect most relevant to capitalism, it gets special attention. Ultimately he argues that the existence of exchange-value implies the existence of a further idea: value.

Marx’s argument has two parts. First, he argues that, in the act of exchange, commodities are being made equivalent to one another, implying the existence of something common to both, which he calls ‘value.’ Secondly, he argues that this common thing must be the objectification of their abstract labor.

This argument is quite unlike the arguments we saw given for the labor theory of value, like the beaver and deer argument or the surplus product argument. It is not presenting a relation between independent and dependent variables, as labor-time determining prices. Instead it is looking at exchange-value and finding it implies the existence of a deeper social substance.

While Elson thinks argument in Capital is ultimately correct, it can be misleading, resulting in the many misinterpretations of Marx like him holding to the LTV. There are also places where certain arguments he makes, or responses to certain objections, will be incomplete unless we incorporate some of the comments he makes outside of Capital.

The first issue here is that Marx’s argument about how exchange implies that commodities are being equated is something that only works within the context of capitalism, but the way he presents it makes it look like it comes from any act of exchange, even outside this capitalist context.

Not all exchange equates the objects being exchanged. For example, we do not need to explain the exchange of Christmas gifts by appealing to some idea of value. Rather, Marx seems to have in mind the act of exchange where something is being bought and sold. Furthermore, this is also being done within the context of a large number of these kinds of exchanges, where the product of any kind of labor could be exchanged for the product of any other kind of labor, and where these exchange-ratios are being determined by this social process in the market.

Understanding this helps to address objections that claim Marx’s argument is formalist and ahistoric. While Marx uses the example of a simple exchange between only two parties trading corn and iron with one another, he is not considering this as an exchange done in complete isolation, but as one instance of exchange within a broader social process. It is an instance of capitalist commodity exchange.

The reduction of the goods exchanged to equivalence depends on their general exchangeability, through the market, of every commodity with every other commodity. Many different commodities are able to express the same value, and do replace one another in the act of exchange itself. This general exchangeability is established as a social, not an individual, process, and can in fact only be found in capitalism where commodity production is dominant.

Marx’s claim that commodity exchange implies their equivalence is not being derived from the ahistoric and formal concept of exchange itself, but from his observation of the specific capitalist process of exchange where goods are being made socially commensurated. This is visibly expressed by their prices.

Marx does not only argue that commodities are being equated on the market though, but that this equivalence implies the need for a common element shared between them, which Marx is calling ‘value.’

Marx’s argument for this isn’t obviously satisfactory. It seems like we could just pick one commodity as a ‘numeraire’ and express the exchange-values of all other commodities in terms of this single one. This would seem to make commodities commensurable with one another without needing to appeal to any further idea of value. Marx’s argument about the equivalence of triangles implying they have a common element doesn’t rule out this kind of approach, and in a way encourages it since this kind of geometric reasoning is a purely mental process.

The critical flaw with the numeraire approach though is that it doesn’t tell us as what are commodities being equated. It tells us nothing about the actual social process which is making commodities commensurable. What is this process that is allowing a commodity to act as a numeraire in the first place?

This question is often ignored by modern economists, instead focused on whether they can build a mathematical model where a certain set of prices are consistent with some criterion they want achieved. Some earlier economists were a bit better here. But while Marx wants to ultimately answer that this equivalence of value is found in abstract labor, they wanted to say it is found in commodities being objects that yield utility, bringing satisfaction.

Marx does not deny that use-value plays an important part in the process of exchange. But he does deny that this can explain their social equivalence.

Marx seems to have two reasons for this. The first reason is that use-value is important in exchange because of the difference in the use-values between what is being traded, not their equivalence. The second reason is that a purely subjective approach to the exchange process leaves out certain crucial features of it.

If commodities are equated as use-values, then this implies they are wanted for the ‘utility’ or ‘satisfaction’ they bring, treating this as a common essence of all wants to which its particular forms are merely a means to that end. Marx denies that our diverse wants can be reduced to a common want this way though. Our everyday experience seems to support this, as different use-values are needed to satisfy different ends (e.g. bread cannot help someone dying of thirst). The 19th-century theories about how utility could be measured and cardinally added or subtracted from each other has also largely been abandoned.

As for the purely subjective approach leaving out crucial features, we can first note that Marx does not deny that there is a subjective element in exchange. Marx is well aware that commodities do not exchange themselves and that the commodity owners are acting according to their own desires. But while exchange-ratios form out of the actions of all commodity owners, each owner also enters into a market where exchange-ratios appear to already be given. It has been decided ‘behind their backs’ in this social process.

This is what leads Marx to treat value as a kind of substantial equivalence. They are not just being commensurated by their owners, but have some unifying common element embodied within them, designated as this separate category of ‘value.’

Elson believes that Marx is using this idea of ‘substance’ in a way similar to the idea of substances in natural science, like with matter or energy. Energy takes on different form as light, heat, mechanical motion, and so on, but we take these all as forms of the same energy. The same is true for matter, as the same chemical substance in different arrangements will have different properties. This materialist view of substance of how the same thing change forms.

As the rate of exchange is determined ‘behind the backs’ of commodity owners, the transformation of one commodity into another is similar to these natural processes. It has its own law operating over and above the will of individuals acting in the market.

But this is a social process. This substantial equivalence must ultimately be something human. While it may appear as a social relation between objects, we know it is really one between people. When considering what relation these commodities share, it is that they are products of human self-activity. Their value is the human vitality spent on their production, embodied in these commodities. It is abstract labor.

This identity with abstract labor is important, since it cannot be, as Ricardo presented it, labor as such. Labor has this two-fold nature of different aspects. As values, if commodities are only quantitatively different, then we must likewise consider only the homogenous aspect of labor that is only different quantitatively.

3. The Phase of Synthesis: From Value to Price

This brings us out of the phase of analysis into the phase of synthesis. Having divided the commodity up into potentia and seen how we have this substance of value as the objectification of abstract labor, we now build back up to the appearance of commodities that we began with.

We are concerned here mostly with how this process of objectification actually happens. How does abstract labor become objectified? Marx calls this the ‘law of value,’ emphasizing the naturalistic aspect of this process, although we’ve seen enough to know Marx’s who idea of laws and determination isn’t rigid here.

For this to happen, abstract labor needs to become expressed through something other than the commodity itself. This means we need another commodity to step in as the bearer of value, as the “value-form.” This is done when it steps in as the “equivalent form” in an exchange. But to really take on this role as equivalent, it needs to be directly exchangeable with what it is exchanging for, and it needs to become universally exchangeable with all other goods so they can have their values compared.

We find this in practice with gold-money. One commodity has been selected out from others, not just arbitrarily but through a social process, and became directly exchangeable with all other commodities. Even if we don’t use gold-money any more, this is an important step in the development of capitalism as Marx’s theory allows.

This universal equivalent becomes the physical embodiment, the incarnation, of abstract value. All other commodities have their value reflected by it.

As the universal equivalent, abstract labor becomes the dominant aspect of labor. To make the money commodity, private and concrete labor is done for the purpose of making something to reflect abstract value, which is also its social role. It also dominates all other commodities as they become brought into this process of capitalist production, which is primarily a way of producing surplus-value. The self-expansion of the money-form of capital dominates the entire process, including labor itself.

This establishes how value is ultimately connecting to exchange-value. The abstract aspect of labor is reflected by the universal equivalent, giving us a way that value connects to price. And it seems, or at least we so far have no reason to doubt, that this exchange also properly reflects the magnitude of these values.

However, Marx signals that this is not the case, and he covers how these do diverge in Volume 3 of Capital. The ultimate reason is that, while Marx begins by looking at commodities as merely products of labor exchanging with one another, the later analysis of capitalist production shows it as more, about being fundamentally about the production of value and surplus-value.

The systematic deviations from the magnitude of value Marx finds comes from how value is ultimately distributed between capitals. This is what is covered in Volume 3.

We also see prices break away from values in another important way, namely the relative autonomy that money has from circulation. People can sell their commodities while holding off from buying, or they can buy immediately. This disruption of the process means the price of commodities, expressed in money, is deviating from their value as it reflects the changes happening to the money itself.

Ultimately this also helps to set up Marx’s theory of crisis. While the ‘law of value’ pushing things towards equilibrium and equality is important to understand, the tendency to disequilibrium is no less real.

4. The Political Implications of Marx’s Value Analysis

We end with the political implications of Marx’s theory. The most important parts here are what this value theory tells us about what we can do about capitalism. Elson thinks it does at least three things.

Firstly, it lets us analyze capitalist production as a whole, rather than being fragmented into these periods of production and exchange. This makes better sense of our experience of exploitation.

Secondly, it lets us understand the crisis-ridden nature of capitalism, as well as how it recovers, changes, and adapts.

Thirdly and finally, it lets us know how the process of exploitation works, and directs us to the real possibility of ending it.

With this, I have finished the ‘brief’ summary of Elson. From here on are my notes where I try to explain back to myself each step in her argument, as well as finding and exploring the sources she cites.

The Longer Restatement of Elson’s Paper

What is Marx’s Theory of Value a Theory Of?

1. The Theory of Value: A Proof of Exploitation?

Marx's value theory is frequently misinterpreted because people misunderstand what the object of his theory is. This happens in different ways.

Firstly, some people think the point of his value theory is to prove the existence of exploitation. Marx talks a lot about how capitalism exploits people because capitalists are getting the “surplus-value” that workers produce beyond what they are paid in wages. Some therefore think that, if Marx’s value theory were disproved, then he could no longer prove that exploitation exists in capitalism.

This is incorrect and the reason becomes clear when we think about how Marx believed exploitation existed in pre-capitalist systems. It is only in capitalism that the product of the worker’s labor appears as a value, since it is only in capitalism where most workers are focused on mass producing commodities for sale on the market. Slave labor was and is obviously exploitative, even if what the slaves made was directly enjoyed by the slave masters instead of being sold.

Marx thought the existence of exploitation was proved in a different way, namely by looking at who owns and controls the means of production, and therefore determines the length of the working-day, making laborers produce not only what they need to support themselves but also the owners of the means of production.

Capital did not invent surplus labour. Wherever a part of society possess the monopoly of the means of production, the worker, free or unfree, must add to the labour-time necessary for his own maintenance an extra quantity of labour-time in order to produce the means of subsistence for the owner of the means of production. (Marx, Capital, Vol. 1, Ch. 10)

There is at least one advantage of this mistaken view of Marx’s value theory: it retains its political aspect. We will see this is not true of other interpretations. Still, this view is mistaken about what Marx is doing with his value theory, which is quite useful for examining capitalist exploitation and telling us what we can do about it, but is not here to prove whether that exploitation exists.

2. The Theory of Value: An Explanation of Prices?

The second mistake is to view Marx’s value theory as an explanation of prices. According to this interpretation, the market equilibrium price of a commodity is determined by its value, which is determined by the average amount of labor needed to make it. This is a common interpretation of Marx, viewing him as having a “labor theory of value” (LTV). This position can be found in Ronald L. Meek, Maurice Dobb, Paul Sweezy, and Michio Morishima.

This also leads Marx to be compared to other people with similar ideas, like Adam Smith and David Ricardo, and focuses the debate around whether this is an accurate theory of price compared to other competing economic theories. It treats all of these theories as having the same object: explaining prices.

For example, Ronald Meek argued that,

‘there is surely little doubt that he (Marx) wanted his theory of value … to do another and more familiar job as well — the same job which theories of value had always been employed to do in economics, that is, to determine prices.’ (Meek, Smith, Marx and After (1977), p. 124)

When these authors try to distinguish what Marx was doing from other economists, it is by saying that Marx’s theory adds a qualitative element, both explaining prices and explaining the social relations underlying commodities.

For example, Dobb writes this:

‘Marx’s theory of value was something more than a theory of value as generally conceived: it had the function not only of explaining exchange-value or prices in a quantitative sense, but of exhibiting the historico-social basis in the labour process of an exchange — or commodity — society with labour power itself become a commodity.’ (Dobb, Introduction to Marx’s A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (1971), p. 11)

In this view, Marx is seen as explaining prices, the process of commodity exchange or circulation, in terms of the more fundamental processes of production.

For example, Sweezy states that:

‘Commodities exchange against each other on the market in certain definite proportions; they also absorb a certain definite quantity (measured in time units) of society’s total available labour force. What is the relation between these two facts? As a first approximation Marx assumes that there is an exact correspondence between exchange ratios and labour-time ratios, or, in other words, that commodities which require an equal time to produce will exchange on a one-to-one basis. This is the simplest formula and hence a good starting point. Deviations which occur in practice can be dealt with in subsequent approximations to reality.’ (Sweezy, The Theory of Capitalist Development (1962), p. 42)

As we can see in this interpretation, Marx’s assumption that commodities exchange at their values, held throughout Volume 1 and 2 of Capital, is treated as him presenting this as a ‘first approximation,’ which is then given up in Volume 3 and we see how values are transformed into prices. The question then becomes a matter of whether Marx adequately solved this ‘transformation problem.’

There are, generally, two major arguments used for the LTV.

The first argument is derived from an example given by Adam Smith where there is an equalization of advantages in a simple ‘deer and beaver’ economy.1 We are asked to imagine a simple society where only two commodities are exchanged: beaver and deer. If it takes one hour to hunt deer and two hours to hunt beaver, then, it is argued, they will tend to trade for a price of 2 deer for 1 beaver, each representing two hours of labor. If we assumed this was not the case, and you were able to trade one deer for one beaver, meaning that the deer is overvalued and the beaver is undervalued. People would switch from hunting beaver to hunting deer since, after making exchanges on the market, they could get the same amount of stuff with only half the work. As people make this switch, beaver gets more scarce as deer becomes more abundant. As the supply changes, the price changes along with it until price equilibrium as they exchange at a rate of 2 to 1. Thus prices are determined by the amount of labor-time needed to produce these commodities (although Smith also kept other considerations in mind too, like how hard each type of labor is or the amount of skill needed for it).

The second argument gives a more intricate and complex explanation for how labor-time is transformed into prices. According to this model, an economy of a given level of technology and sociological conditions will produce a certain mass of products. This mass of products will contain a certain surplus over and above what actually goes back to the workers, which then becomes profit and other forms of non-wage income (rent, taxes, etc.). This size of this surplus, typically measured in labor-time, sets the aggregate level of profit over the economy, which is then distributed across various industries which will tend toward a certain average rate of profit and will accordingly set the price of all commodities.

This can be seen in Meek:

‘In their basic models, all three economists (i.e. Ricardo, Marx and Sraffa) in effect envisage a set of technological and sociological conditions in which a net product or surplus is produced (over and above the subsistence of the worker, which is usually conceived to be determined by physiological and social conditions.) The magnitude of this net product or surplus is assumed to be given independently of prices, and to limit and determine the aggregate level of the profits (and other non-wage incomes) which are paid out of it. The main thing which the models are designed to show is that under the postulated conditions of production the process of distribution of the surplus will result in the simultaneous formation of a determinate average rate of profit and a determinate set of prices for all commodities.’ (Meek, Smith, Marx and After (1977), p. 160)

Both versions of the LTV treat the labor-time socially necessary to produce these commodities as something entirely distinct and independent from their price. It is focused entirely on the process of production, and sees market circulation as an entirely separate process, even if connected to production. We have a relation where labor-time acts as an independent-variable determine prices as the dependent variable. In this view, we could, at least in theory, calculate what a commodity’s value is entirely independently from their prices, and therefore deduce what the market equilibrium price would be. The world might be so complex that we could never do this in practice, but the possibility exists in principle and helps to establish Marx’s value theory as properly scientific.

Interpretations of Marx as having yet another labor-theory of value tends to depoliticize his actual value theory, turning him into just another theorist trying to mathematically model prices in capitalism.

An extreme example of this can be seen in Michio Morishima, in which,

‘the classical labour theory of value is rigorously mathematised in a familiar form parallel to Leontief’s inter-sectoral price-cost equations. The hidden assumptions are all revealed and, by the use of the mathematics of the input-output analysis, the comparative statical laws concerning the behaviour of the relative values of commodities (in terms of a standard commodity arbitrarily chosen) are proved. There is a duality between physical outputs and values of commodities, which is similar to the duality between physical outputs and competitive prices. It is seen that the labour theory of value may be compatible with the utility theory of consumers demand or any of its improved variations.’

[…]

‘(values) are determined only by technological coefficients … they are independent of the market, the class-structure of society, taxes and so on.’

(Morishima, Marx’s Economics (1973), p. 5 and 15

Thus all the politics is removed from Marx’s value theory to make him a respectable proto-mathematical economist.

Some Marxists have tried to push back against this tendency, but because they accept the same premises as the Sweezy-Meek-Dobb tradition, they have decided that to retain the politics of Marx they need reject value itself!

For example, we find in Ian Steedman that,

‘the project of providing a materialist account of capitalist societies is dependent on Marx’s value magnitude analysis only in the negative sense that continued adherence to the latter is a major fetter on the development of the former.’ (Steedman, Marx after Sraffa (1977), p. 207)

Similar ideas can be found in Geoffrey Hodgson. Both of these figures instead struggle with the first misinterpretation, focusing on a proof of exploitation which could be understood perfectly well in terms of appropriating a surplus-product without involving ‘value’ whatsoever.

Steedman is so critical of value here because the socially-necessary labor-time embodied in commodities has been found to be at best redundant to, and at worst incapable of, explaining equilibrium prices. Attempts to preserve a traditional Anglo-Saxon version of the LTV tend to dissolve into positions even more Ricardian than the Neo-Ricardians.

Elson has no intention of rescuing the traditional “Labor Theory of Value”. Instead, she wants to give an entirely different reading of Marx’s value theory which would make critiques given against it, like from Piero Sraffa, redundant.

Elson believes she is doing something similar to Tony Cutler, Barry Hindess, Athar Hussain, and Paul Q. Hirst, the authors of Marx’s ‘Capital’ and Capitalism Today (1977) hereon referred to as ‘Cutler et al.’ They argue that value is not a ‘general determinant’ of prices and exchange-values, i.e. it is not a a singular ‘origin’ or ‘cause’ of prices and profits. They say this claim puts them outside of both Marxist theory and conventional economic theory.

Elson agrees that value is not a ‘general determinant’ in this sense, but denies that that Marx ever intended his value theory to be treated this way. Rather, Marx’s idea of ‘determination’ is quite different from how the authors of this section think about it.

3. An Abstract Labor Theory of Value?

Elson is not the first person to question whether the labor theory of value exists in Marx, at least in the versions given above.

Some have argued that Marx does hold to the LTV, but has developed his own version distinct from what we might find in Ricardo because of how he developed this idea of ‘abstract labor.’

There is some truth here. Marx certainly does claim he differs from Ricardo because of the attention he gives to the form of labor and because of how he distinguishes abstract labor and concrete labor.

At first sight a commodity presented itself to us as a complex of two things – use value and exchange value. Later on, we saw also that labour, too, possesses the same two-fold nature; for, so far as it finds expression in value, it does not possess the same characteristics that belong to it as a creator of use values. I was the first to point out and to examine critically this two-fold nature of the labour contained in commodities. (Marx, Capital, Vol. 1, Ch. 1)

This point is taken up by Himmelweit and Mohun in their essay “The Anomalies of Capital” (1978). They base their response to Steedman on,

‘a distinction between Ricardian embodied-labour theory of value and a Marxian theory of value based on the category of abstract labour. While the former is intended immediately to be a theory of price, the latter is only so after several mediations.’ (Himmelweit and Mohun, “The Anomalies of Capital” (1978), p. 94)

They are claiming that Steedman’s critique of the LTV only applies to the version presented by David Ricardo, but which Marx avoids because of how he uses this idea of abstract labor.

This response is not convincing for two reasons.

Firstly, Steedman claims to have treated labor as abstract labor, and was applying his critique to an ‘abstract labor theory of value.’ Himmelweit and Mohun act as if he did not, and do not confront this claim. Perhaps they had a different understanding of abstract labor from Steedman, but they’d need to address that in their critique.

Secondly, this makes their argument circular. They are deriving the concept of abstract labor from the commodity form, but then are trying to use the same concept to explain the commodity form.

Elson affirms that the distinction between abstract and concrete labor really is important as a way to distinguish Marx from Ricardo, but it is not the only way they differ. Even more fundamental than this is their method of analysis.

4. Labor as the Object of Marx’s Value Theory

The object of Marx's theory of value was not exploitation or prices, but labor itself. Marx wasn’t trying to figure out why prices are what they are and finding that the answer is found in labor. Rather, he was trying to figure out why labor takes on the form that it does in capitalism and what the political consequences follow from this.

Political Economy has indeed analysed, however incompletely, value and its magnitude, and has discovered what lies beneath these forms. But it has never once asked the question why labour is represented by the value of its product and labour time by the magnitude of that value. These formulæ, which bear it stamped upon them in unmistakable letters that they belong to a state of society, in which the process of production has the mastery over man, instead of being controlled by him, such formulæ appear to the bourgeois intellect to be as much a self-evident necessity imposed by Nature as productive labour itself. (Marx, Capital, Vol. 1, Ch. 1)

Marx begins Capital by looking at commodities because that is the "simplest social form in which the labour product is represented in contemporary society." (Marx, Marginal Notes on Wagner) Labor, not price, is the object of his theory.

This also helps to explain the flaw of Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk’s critique of Marx (see Karl Marx and the Close of His System). Böhm-Bawerk argued that Marx had ‘rigged’ his explanation of prices, discovering that all commodities share the feature of being products of labor, by deliberately leaving out of consideration things that have prices yet are not products of labor (e.g. the price of untouched land). If Marx is not trying to study prices, but is instead trying to study how labor is represented in capitalism, this exclusion makes much more sense.

5. A Possible Misconception: The Social Distribution of Labor

When Marx analyzes the form labor takes in capitalism, he does not consider this to be merely a question of distribution.

When people do read Marx this way, it is usually as a result of this quote written in a 1868 letter from Marx to Kugelmann:

Every child knows a nation which ceased to work, I will not say for a year, but even for a few weeks, would perish. Every child knows, too, that the masses of products corresponding to the different needs required different and quantitatively determined masses of the total labor of society. That this necessity of the distribution of social labor in definite proportions cannot possibly be done away with by a particular form of social production but can only change the mode of its appearance, is self-evident. No natural laws can be done away with. What can change in historically different circumstances is only the form in which these laws assert themselves. And the form in which this proportional distribution of labor asserts itself, in the state of society where the interconnection of social labor is manifested in the private exchange of the individual products of labor, is precisely the exchange value of these products.

Taken by itself, this passage can lead someone to think Marx is only looking at labor as individuals are distributed and connected within a pre-given structure of tasks that must be completed.

You can find this reading of Marx in very different Marxist tendencies, like with the ‘Hegelian’ I. I. Rubin or the ‘anti-Hegelian’ Louis Althusser. Both gave ultimate causal significance for the distribution of labor to a certain pre-given set of technical and material conditions of production.

This kind of view tends to simply reintroduce the LTV, although in a more subtle and reciprocal way where labor-time and exchange-value mutually determine each other.

For example, we can see this with Rubin:

In a simple commodity economy, the exchange of 10 hours of labor in one branch of production, for example shoemaking, for the product of 8 hours of labor in another branch, for example clothing production, necessarily leads (if the shoemaker and clothesmaker are equally qualified) to different advantages of production in the two branches, and to the transfer of labor from shoemaking to clothing production. (Rubin, Essays on Marx’s Theory of Value, Ch. 11)

This is basically the same argument Sweezy gives, except that Sweezy properly credits this argument back to Adam Smith. Rubin claims to be avoiding Smith’s mistakes because this ‘equalization of advantages’ is being enforced by an objective social process forcing individuals to behave this way.

This argument is wrong. There is no social pressure in simple commodity production for producers (using their own or their family’s labor, and not hired labor) to compare the different rewards an hour’s labor gets in different branches of production. It is only in capitalist production that the capitalists are forced by market competition to account for all labor-time spent in production. And when capitalists do this kind of accounting, they do it in terms of money, not hours of labor, because it isn’t their own labor-time that they need to account for.

A more significant break here with Sweezy is that Rubin does not present value as a category of the production process, whereas Sweezy does. Because of this, Rubin tends to obscure the relation between value and exchange-value, while Sweezy (and Meek, Dobb, etc.) tends to obscure the relation between value and labor-time.

For example, Rubin claims that:

[V]alue represents that average level around which market prices fluctuate and with which the prices would coincide if social labor were proportionally distributed among the various branches of production. (Rubin, Essays on Marx’s Theory of Value, Ch. 8)

Thus value is a category of circulation.

By contrast, we see Meek claim that:

‘Marx began by defining the ‘value’ of a commodity as the total quantity of labour which was normally required from first to last to produce it.’ (Meek, Smith, Marx and After (1977), p. 95)

Thus value is a category of production.

Like other supporters of the LTV, Rubin also treats production as a distinct process where we find the ‘independent variables’ determining prices as a dependent variable.

Rubin writes that:

In this way the moving force which transforms the entire system of value originates in the material-technical process of production. The increase of productivity of labor is expressed in a decrease of the quantity of concrete labor which is factually used up in production, on the average. As a result of this (because of the dual character of labor, as concrete and abstract), the quantity of this labor, which is considered "social" or "abstract," i.e., as a share of the total, homogeneous labor of the society, decreases. The increase of productivity of labor changes the quantity of abstract labor necessary for production. It causes a change in the value of the product of labor. A change in the value of products in turn affects the distribution of social labor among the various branches of production. Productivity of labor - abstract labor-value - distribution of social labor: this is the schema of a commodity economy in which value plays the role of regulator, establishing equilibrium in the distribution of social labor among the various branches of the national economy (accompanied by constant deviations and disturbances). The law of value is the law of equilibrium of the commodity economy. (Rubin, Essays on Marx’s Theory of Value, Ch. 8)

Rubin is therefore still in the terrain of the labor theory of value. Like them, the object of his theory is in the process of circulation. The only difference is he has widened this to include the circulation of labor-time as well as the products of labor.

6. The Indeterminateness of Human Labor

If Marx is not focused on the circulation/distribution of labor, filling in slots in the pre-given structure of production, then what is his object?

We could try saying that Marx is determining both the structure of production and how labor is distributed within it. But this is too mechanical a way of thinking.

Marx rejected this kind of ‘pre-given structure’ analysis because labor is, by its nature, a dynamic and living force.

Labour is the living, form-giving fire; it is the transitoriness of things, their temporality, as their formation by living time. (Marx, Grundrisse)

Labor is marked by this fluidity and potential. Societies must ‘fix’ or ‘objectify’ this potential so that particular goods are made by particular people in particular ways.

This fluidity of labor, and the need to objectify it, is true of all societies, but becomes most apparent in industrial societies where people can and do frequently change jobs instead of being fixed into them by tradition, family, religion, etc.

As Marx put it:

[W]e see at a glance that, in our capitalist society, a given portion of human labour is, in accordance with the varying demand, at one time supplied in the form of tailoring, at another in the form of weaving. This change may possibly not take place without friction, but take place it must. (Marx, Capital, Vol. 1, Ch. 1)

Because we can see people regularly switch jobs in capitalism, and labor gets redistributed according to rising and falling demand, capitalism makes the inherent fluidity of labor immediately apparent. That this is not immediately apparent in pre-capitalist societies which limited people’s ability to move jobs doesn’t make it any less true.

The fundamental question around labor then for any society is 'how is labor determined?'

By ‘determination’ here, we do not mean to deny the element of individual choice. Rather, we mean that individuals are limited in their choices to the options available to them. They cannot choose anything, as if the world would be built back up from scratch to accommodate them.

This is an idea of determination which is, ironically, non-deterministic. Marx emphasizes that determination is not merely an exercise of our individual will, but it is not independent of our individual wills either.

The social structure and the State are continually evolving out of the life-process of definite individuals, but of individuals, not as they may appear in their own or other people’s imagination, but as they really are; i.e. as they operate, produce materially, and hence as they work under definite material limits, presuppositions and conditions independent of their will. (Marx, The German Ideology)

Thinking about the ‘distribution’ of labor is not a good metaphor since it lends itself to thinking people are being distributed into this pre-given structure, which is not itself being determined.

What we actually need is to understand a process moving from the indeterminate potential to the determined actual. Marx’s Capital is an attempt to provide that, using a method of investigation that is uniquely his own, and which Marx claims has not been used previously by other economists.

[T]he method of analysis which I have employed, and which had not previously been applied to economic subjects, makes the reading of the first chapters rather arduous, and it is to be feared that the French public, always impatient to come to a conclusion, eager to know the connexion between general principles and the immediate questions that have aroused their passions, may be disheartened because they will be unable to move on at once.

That is a disadvantage I am powerless to overcome, unless it be by forewarning and forearming those readers who zealously seek the truth. There is no royal road to science, and only those who do not dread the fatiguing climb of its steep paths have a chance of gaining its luminous summits. (Marx, Capital, Vol. 1, Preface to the French Edition)

This unique method might explain why so many people misread Capital.

In the next section, we will analyze what Marx’s method was and how it is distinguished from those who support the Labor Theory of Value. Instead, Elson presents Marx as having a ‘Value Theory of Labor.’

Elson also wants to emphasize that she is only claiming that Marx developed this method to its fullest in Capital. In some of Marx’s earlier texts, while he was still developing this method, we can find both elements of a ‘labor theory of value’ and a ‘value theory of labor.’

For example, this can be seen in his earlier Critique of Political Economy (1859), published eight years before Capital, where Marx does not make a clear distinction between value and exchange-value.

Instead, we see Marx developing his theory in Theories of Surplus-Value, especially his critique of Samuel Bailey. The focus of Elson’s paper is therefore primarily on Capital, some on Theories of Surplus-Value, and a few passages from the Critique of Political Economy related to money.

Misplaced Concreteness and Marx’s Method of Abstraction

1. Rationalist Concepts of Determination

The interpretations of Marx’s value theory we have looked at so far all share a common error: they involve a ‘misplaced concreteness’ so that the theory can be understood as a relation between independent variables (found in the production process) and dependent variables (found in the circulation process).

It is simply taken for granted that any theory needs separable determining factors that are discretely distinct from what they are determining.

Althusser’s ‘structural causality’ is no exception here. He just puts the independent variables one stage back, behind the ‘structure’ of the global mode of production being determined by things like labor power, direct laborers and masters, objects and instruments of production, etc.

Cutler et al.’s abandonment of Althusser does not break with this view either. They get rid of his self-reproduction ‘structures,’ but keep these elements as the ‘conditions of existence.’ They are just more agnostic about their choice of independent variables.

This view presents determination as an effect of discretely distinct elements or factors on other separate elements or factors, whose general form is given but their position within a certain range is not.

This is a ‘rationalist’ method. It assumes the material world is like symbols of math or logic: separate, self-bound, and related to each other in the same way.

Marx did not use this method. His theory of value is not constructed along rationalist lines.

2. Determination in Marx’s Theory of Value: The Relation Between Labor-Time, Value, and Exchange-Value

Labor-Time and Value

Bertell Ollman has pointed out that Marx’s idea of determination is not a relationship of independent and dependent variables. Instead, the thing doing the determining is also a part of what is being determined.

For example, Marx argued that the ‘superstructures’ of society, like the legal system, are determined by the relations of production. But some elements of that superstructure are also part of the relations of production. Property relations are a system of legal claims, part of the superstructure, but are simultaneously part of the relations of production determining that superstructure.

We see Marx making a similar point in the first chapter of Capital.

Consider the first time Marx discusses something being determined in Capital:

Some people might think that if the value of a commodity is determined by the quantity of labour spent on it, the more idle and unskilful the labourer, the more valuable would his commodity be, because more time would be required in its production. The labour, however, that forms the substance of value, is homogeneous human labour, expenditure of one uniform labour power.

[…]

We see then that that which determines the magnitude of the value of any article is the amount of labour socially necessary, or the labour time socially necessary for its production. (Marx, Capital, Vol. 1, Ch. 1)

If we mix up ‘value’ here with ‘exchange-value’ or ‘price,’ it is easy to read this passage as advocating for a labor theory of value. The commodity’s value/exchange-value is being determined by the amount of labor time socially necessary to make it. But Marx early clearly distinguished value from exchange-value, and made it clear he only as the former in mind here.

So how is Marx saying value is being determined? Is it ‘determined’ in the sense of ‘logically defined?’ Is value just another term for socially necessary labor-time? Obviously not, since socially necessary labor-time isn’t simply the same thing as value, as if they were just interchangeable terms.

Rather, value is a certain way that a certain aspect of labor-time, namely when it is considered simply as an expenditure of human labor-power in general, i.e. abstract labor. This abstract labor is being ‘objectified’ or ‘materialized’ by capitalism.

Value is not just the same thing as abstract labor, but a particular social form that abstract labor is being given within capitalism. This is not labor being physically objectified, like how the concrete labor of carpentry might be objectified by its product of a wooden chair, but how it is being socially objectified, giving the commodity a kind of “unsubstantial reality” or “phantomlike objectivity.”

Let us now consider the residue of each of these products; it consists of the same unsubstantial reality in each, a mere congelation of homogeneous human labour, of labour power expended without regard to the mode of its expenditure. All that these things now tell us is, that human labour power has been expended in their production, that human labour is embodied in them. When looked at as crystals of this social substance, common to them all, they are – Values. (Marx, Capital, Vol. 1, Ch. 1)

Also consider the metaphors Marx is using here. Homogenous human labor is being ‘congealed.’ We are working with ‘crystals’ of this social substance.

This is how Marx thinks about determination. We do not have a relation of independent and dependent variables, where abstract labor and value are two separate things and the former is determining the latter, like we might see in mathematical formulas. Rather, homogenous human labor, i.e. abstract labor, is determining value in a way similar to how the quantity of a chemical substance in its liquid-form will determine the size of its crystal or jellied form.

As Elson puts it:

There is a continuity as well as a difference between what determines and what is determined.

Value and Exchange-Value

So Marx thinks abstract labor is being crystallized into this social form of ‘value.’ What about the relation between value and exchange-value? How does that work?

At first glance, these seem even more like entirely separate variables. Value is a quantity of socially-necessary abstract labor-time. Exchange-value is the quantity of one commodity needed to exchange for some quantity of another commodity.

These seem quite different from one another, so it seems like we could only have a relation here, if any at all, between independent and dependent variables, as is argued by the labor theory of value.

True, Marx does make the following claim:

[E]xchange value, generally, is only the mode of expression, the phenomenal form, of something contained in it, yet distinguishable from it [i.e. value]. (Marx, Capital, Vol. 1, Ch. 1)

This seems to imply we have a relation like before, where there is a continuity and difference between value and its ‘form of appearance’ or ‘phenomenal form’ as exchange-value.

But maybe this only means that exchange-value is approximating value, even as they remain two entirely separate things. That is how Steedman seems to have interpreted Marx, anyway. They seem even more independent from one another when we consider how they are measured in two very different ways, value being measures by labor-time and exchange-value being measured in terms of some other commodity, typically money.

However, it is very hard to maintain this interpretation when we consider the third section of chapter 1, ‘The Value-Form or Exchange Value’. Here Marx suggests that, without exchange-value, then value would be a mere abstraction, lacking any practical reality. Value is therefore not independent from exchange-value, but is manifested through it.

If we say that, as values, commodities are mere congelations of human labour, we reduce them by our analysis, it is true, to the abstraction, value; but we ascribe to this value no form apart from their bodily form. (Marx, Capital, Vol. 1, Ch. 1)

Just like with labor-time and value, there is both a continuity and a difference between value and exchange-value. Value only becomes manifested by exchange-value. If a product of labor counts as a value, then this must be reflected in some immediately apparent attribute.

This is not to say that we need to immediately recognize what this immediately apparent attribute is reflecting though. As Marx clarified,

Value, therefore, does not stalk about with a label describing what it is. It is value, rather, that converts every product into a social hieroglyphic. (Marx, Capital, Vol. 1, Ch. 1)

The simplest form of this reflection is when two commodities stand in a relation of equivalence to each other, the second commodity serving as the material to express the value of the first.

However, this is a very limited expression of value, only dealing with two commodities. To adequately express value, it needs a universal equivalent. It needs a commodity that is directly exchangeable with all other commodities and whose use-value is precisely this interchangeability.

As the process of exchange develops, one commodity is set apart to play this role. As Marx puts it,

Money is a crystal formed of necessity in the course of the exchanges, whereby different products of labour are practically equated to one another and thus by practice converted into commodities. (Marx, Capital, Vol. 1, Ch. 2)

The form of value is therefore found in a commodity’s price. The process which determines a commodity’s price is not independent from the formation of its value.

[T]he money-form is but the reflex, thrown upon one single commodity, of the value relations between all the rest. (Marx, Capital, Vol. 1, Ch. 2)

Just because one commodity is turned into money does not mean that money must always be commodity money (i.e. gold).

Marx argued that,

…money can, in certain functions, be replaced by mere symbols of itself… (Marx, Capital, Vol. 1, Ch. 2)

He also points out that,

The function of gold as coin becomes completely independent of the metallic value of that gold. Therefore things that are relatively without value, such as paper notes, can serve as coins in its place. This purely symbolic character is to a certain extent masked in metal tokens. In paper money it stands out plainly. (Marx, Capital, Vol. 1, Ch. 3)

Instead, what Marx is actually arguing is that money cannot be completely autonomous, as if it were established by mere convention. It must come about as a result of this ‘blind’ social process. Marx argued that not recognizing this was the flaw of Benjamin Franklin’s analysis of money:

He [Franklin] therefore fails to see the intrinsic connection between money and labour which posits exchange-value, but on the contrary regards money as a convenient technical device which has been introduced into the sphere of exchange from outside. (Marx, Critique of Political Economy, Note A)

Value and price are therefore not two completely separate variables. As he says, there is an “intrinsic connection” between them.

This does not mean that value and price are identical, as if they were two terms for the same thing. Marx explicitly critiques Bailey for thinking that “Value equals price” (see Theories of Surplus-Value). There is a continuity and a difference in price, regardless of whether this is expressed in gold or paper.

In summary, Capital does not treat labor-time, value, and exchange-value as three discretely distinct variables, nor are they identical with one another. There is a relation of continuity and a difference between, rather than one of independent and dependent variables.

3. Measures of Value: Labor-Time and Money

Value Cannot Be Measured Apart from Price

We saw that the labor theory of value required us to be able to, at least in principle, measure value directly in terms of labor-time, independently from price. But the above analysis does not imply any such possibility, since they are all interconnected.

This also helps to explain Marx’s own criticism of any labor-money scheme seen in John Gray, which Marx presents as a precursor to Proudhon’s own idea of a People’s Bank. By this plan, the national bank would determine how much labor-time is needed for each commodity. The bank would then purchase these commodities, issuing a certificate stating its value according to this labor-time, which could then be used to purchase any other commodity made with an equal amount of labor-time.

Marx does not deal with this at length in Capital, referring us instead to a lengthier critique he made in his Critique.

Since labour-time is the intrinsic measure of value, why use another extraneous standard as well? Why is exchange-value transformed into price? Why is the value of all commodities computed in terms of an exclusive commodity, which thus becomes the adequate expression of exchange-value, i.e., money? This was the problem which Gray had to solve. But instead of solving it, he assumed that commodities could be directly compared with one another as products of social labour. But they are only comparable as the things they are. Commodities are the direct products of isolated independent individual kinds of labour, and through their alienation in the course of individual exchange they must prove that they are general social labour, in other words, on the basis of commodity production, labour becomes social labour only as a result of the universal alienation of individual kinds of labour. But as Gray presupposes that the labour-time contained in commodities is immediately social labour-time, he presupposes that it is communal labour-time or labour-time of directly associated individuals. (Marx, Critique of Political Economy, Ch. 2 Part 1.B)

The main problem with Gray’s plan is that he assumed the labor-times needed for each commodity were directly comparable. But Marx denies this, arguing the only labor we can directly observe is “isolated independent individual kinds of labor.”

In short, we can only observe the private and concrete aspects of labor, whereas value is concerned with the social and abstract aspects of labor. As Marx argued earlier, these aspects only become evident through exchange.

But the different kinds of individual labour represented in these particular use-values, in fact, become labour in general, and in this way social labour, only by actually being exchanged for one another in quantities which are proportional to the labour-time contained in them. Social labour-time exists in these commodities in a latent state, so to speak, and becomes evident only in the course of their exchange. The point of departure is not the labour of individuals considered as social labour, but on the contrary the particular kinds of labour of private individuals, i.e., labour which proves that it is universal social labour only by the supersession of its original character in the exchange process. Universal social labour is consequently not a ready-made prerequisite but an emerging result. (Marx, Critique of Political Economy, Ch. 1)

If the social-necessity of labor cannot be established independently from their price, then values cannot be directly observed or calculated independently from prices.

Immanent and External Measures

If only prices manifest value, then how can Marx claim that labor-time is acting as a measure of value?

The answer lies in Marx’s distinction between immanent and external measures. This distinction is found elsewhere in Marx, but is barely touched on in Capital, no doubt adding to more confused readings. The distinction is implicit in Marx’s analogy of measuring weight, and is only explicit at the beginning of Marx’s chapter on money:

Money as a measure of value, is the phenomenal form that must of necessity be assumed by that measure of value which is immanent in commodities, labour-time. (Marx, Capital, Vol. 1, Ch. 3)

A more complete elaboration on the distinction between immanent and external measures is found in Marx’s critique of Bailey in Theories of Surplus Value.

An 'immanent' measure is the characteristic that allows something to be measured in terms of pure quantity.

An 'external' measure is the medium in which the measurements of the immanent measure are actually made.

The concept of an immanent measure does not strictly determine what the external measure will be. There is room for convention in what medium is being used, how things are calibrated, etc.

This is not, as Cutler et al. suggest, a distinction between a ‘realist’ theory of measurement to a ‘formalist’ one. Rather, Marx is suggesting that there are realist and formalist aspects of cardinal measurability (i.e. when something can be measured as an absolute quantity that can be added or subtracted from, in contrast to measuring something merely as ‘bigger’ or ‘smaller’ or ranked in a certain order).

Something can only be cardinally measured when it has certain real properties. We can see this in the example of measuring weight.

The external measure of weight is, by convention, iron. We might have chosen another metal, like steel, and we can use different units like ounces, pounds, grams, etc.

But iron can only act as an external measure if both it and whatever is being measured actually have weight. Weight itself is the immanent measure.

The actual act of measuring weight therefore involves bringing two objects into comparison, both of which have weight, and where one of these objects is acting as an external measure and whose weight is presupposed.

Labor-Time as an Immanent Measure

When Marx says that labor-time is the measure of value, he means it is the immanent measure of value. In other words, it is because commodities are objectifications of abstract or ‘indifferent’ labor-time, hours that can be added to and subtracted from one another, that we are capable of cardinally measuring it.

This does not work for commodities as products of concrete labor, since then we would not be dealing with pure time. We would have three hours of tailoring added to five hours of weaving. We could rank these in terms of hours spent on each task, but we cannot directly add them together since they are qualitatively different. We would have to arbitrarily assume that one hour of one task is equal to one hour of any other task.

The argument that labor-time is the immanent measure of value does not imply that labor-time can work as a medium of measurement. In fact, it actively excludes it since we cannot in practice separate the abstract and concrete aspects of labor. The only way we could do that is by arbitrarily assuming away the qualitative differences between different kinds of labor, which Marx refuses to do.

It is surprising that Cutler et al. missed this distinction between immanent and external measures. If they had, they might have realized that it is money, not labor-time, which Marx uses as the standard of measurement throughout Capital.

Marx stresses that labor-time is the measure of value because he wants to emphasize that money is not what makes the products of labor commensurable (i.e. measurable by the same standard). Rather, they are commensurable because they are objectifications of the same abstract aspect of labor.

These confusions are not new. Marx made the same point in a comment about the early French political economist Boisguillebert:

Boisguillebert’s work proves that it is possible to regard labour-time as the measure of the value of commodities, while confusing the labour which is materialised in the exchange-value of commodities and measured in time units with the direct physical activity of individuals. (Marx, Critique of Political Economy, Note A)

It follows from this that the value-magnitude equations Marx introduces in Capital are not referring to directly observable amounts of labor-time. Rather, they are a way of indicating this intrinsic character of the directly observable amounts of money.

Marx generally introduces these equations in a general form, like saying the value of a commodity = (c + v) + s, and then following this with a specific example. These specific examples are always presented in terms of money, and never in terms of hours of labor-time. For example:

When the process of production is finished, we get a commodity whose value = (c + v) + s, where s is the surplus-value; or taking our former figures, the value of this commodity may be (£410 const. + £90 var.) + £90 surpl. The original capital has now changed from C to C', from £500 to £590. The difference is s or a surplus-value of £90. (Marx, Capital, Vol. 1, Ch. 9)

This does not mean Marx is identifying value with price. Rather, he is indicating the inner value-character of these amounts of money. Marx is not simply working at the level of money either because he wants to also uncover certain social relations that do not appear directly in the money-form, like the rate of surplus-value.