Introduction

Paxton’s Anatomy of Fascism can be read here. Read my notes on chapter six here.

Anatomy of Fascism was published in 2004. In this chapter, Paxton reviews what was then the current state of political affairs to see where he believed fascism was or could be developing. Given the dramatic move towards authoritarianism with the alt-right and figures like Trump, Bolsonaro, Meloni, Putin, Netanyahu, Milei, and others, it is interesting and somewhat depressing to see what signs of this existed twenty years ago.

This chapter also brings in what is meant to be a clear contrast between fascism and other movements frequently called fascist but which Paxton would say are merely authoritarian. For example, Pinochet in Chile is frequently described as a fascist, but there is the interesting caveat that he worked as a proxy government for the United States. However, it is hard to identify traditional fascist elements like their expansionism. His power rested not on his own charisma for a nationalist movement, but directly on US support.

One major change since then seems to be the very mainstream denunciation of the electoral systems. While Paxton believed that no “normalized” fascist movement seems to call for a one-party dictatorship, the demonization of the opposing party and conspiracy theories surrounding elections that just automatically dismiss their legitimacy seems to serve an extremely similar function.

Chapter 7: Other Times, Other Places

Is Fascism Still Possible?

The start of fascism was located in chapter 2 with the first crisis of mass democracy, namely with WW1 and the Bolshevik Revolution. But has fascism ended? Is there still an opportunity for it to take power? Many have argued it has, and that it cannot.

Fascism had its “era” that ended in 1945 due to the particular issues of the time. After 1945, Hitler inspired revulsion, and Mussolini derision. The crimes of fascism are well documented. The economy boomed after 1945, and globalization reached new heights. Nuclear weapons put a more firm limit on war expansionism. And the revolutionary threat does not seem nearly as dire.

However, this so-called end of fascism was cast into serious doubt in the 1990s. There was the ethnic cleansing in the Balkans. Nationalism revived in post-communist eastern Europe.

The “skinhead” movement began to rise and enacted violence against immigrants in western Europe.

We also saw fascistic parties finding some political success. For example, the “Alleanza Nazionale,” the direct descendant of the neofascist MSI…

…Jörg Haider’s “Freedom Party” in Austria and its courting of Nazi veterans…

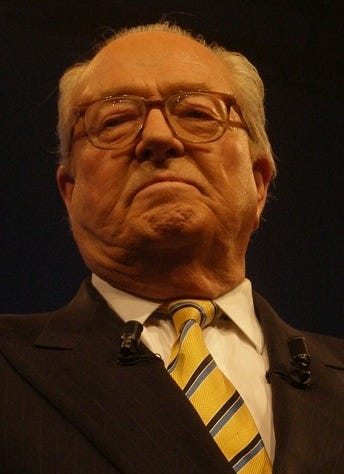

…the astonishing success of the far-right French politician Jean-Marie Le Pen…

…and the anti-immigrant Pym Fortuyn in the Netherlands.

A whole host of far-right “grouplets” have kept the far-Right alive.

Whether one believes fascism is still possible depends on what we understand fascism to be, of course. Those who are worried about fascism returning often just identify it with overtly violent and racist nationalism. Those who claim fascism died in 1945 typically claim its violent moves to war and exclusion are not possible in the modern complex world. The more common position holds that fascist movements exist, but do not have the right conditions to form a mass movement.

Properly identifying modern fascist movements is made harder because many fascists might not self-identify that way, since the word itself is taboo.

The postwar movements and parties themselves have been no less broad than interwar fascisms, capable of bringing authentic admirers of Mussolini and Hitler into the same tent with one issue voters and floating protesters. Their leaders have become adept at presenting a moderate face to the general public while privately welcoming outright fascists sympathizers with coded words about accepting one's history, restoring national pride, or recognizing the valor of combatants on all sides.

Inoculation against the original fascism is inherently temporary, as eyewitnesses begin to die off.

But a future fascism need not be a repeat of the original fascism.

In any event, a fascism of the future - an emergency response to some still unimagined crisis - need not resemble classical fascism perfectly and its outward signs and symbols. Some future movement that would "give up free institutions" in order to perform the same functions of mass mobilization for the reunification, purification, and regeneration of some troubled group would undoubtedly call itself something else and draw on fresh symbols. That would not make it any less dangerous.

For example, while a new fascism would necessarily diabolize some enemy, both internal and external, the enemy would not necessarily be Jews. An authentically popular American fascism would be pious, anti-black, and since September 11th, 2001, anti-Islamic as well; in western Europe, secular and, these days, more likely anti-Islamic than anti-Semitic; in Russia and eastern Europe, religious, anti-Semitic, Slavophile, and anti-Western. New fascisms would probably prefer the mainstream patriotic dress of their own place and time to alien swastikas or fasces. The British moralist George Orwell noted in the 1930s that an authentic British fascism would come reassuringly clad in sober English dress. There is no sartorial litmus test for fascism.

It is easy to admit that fascism still exists widespread at Stage One. Stage Two however faces a stricter test. But this test need not be exact replicas of the fascism of the 1920s. Historic fascisms were shaped by the alliances they made at stages Two and Three. Carbon copies of the original fascism seem too exotic to succeed.

If important elements of the conservative elite began to cultivate or even tolerate them [fascists] as weapons against some internal enemy, such as immigrants, we are approaching Stage Two.

Since 1945, stage Two had only been reached only by radical Right movements that "normalize" themselves. They are usually distinct from the center Right only by their awkward friends and occasional verbal excesses.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union, functionally similar fascist movements have become quite common. To recognize this, we need to look past superficial symbols.

Western Europe is the area with the strongest fascist legacy since 1945.

Western Europe since 1945

Germany

Some fascists kept the faith after 1945, with this obviously being the most concerning for German fascists.

The population's support for Nazism fell to 3% in the early 1950s, thanks to the return of German refugees. The radical right was also divided. The Socialist Reich Party was banned in 1952 for being too openly neo-Nazi, and it's rival, the German Reich Party, had only 1% of the vote.

Various factions joined together to make the National Democratic Party in 1964. But it never reached the necessary 5% support to enter federal elections. Its closest chance was in 1969.

Another far right party, the Republican Party gained some prominence in 1989, but then lost it.

Italy

In Italy, the Movimiento Sociale Italiano (MSI) was Mussolini's most direct heir, founded by Giorgio Almirante in 1946. It only gained some prominence in 1969, after merging with some monarchists. It mostly stayed a distant fourth.

The red scare of 1972 helped, and so did 1983 when the Christian Democrats opened themselves up to socialists. When Fernando Tambroni made a coalition with MSI in 1960, anti-fascist backlash forced him to resign. No one else would touch MSI for 30 years.

MSI did best in the south, where there had been no civil war in 1944. Some MSI people have done fairly well politically. The Duce's granddaughter Alessandra Mussolini, who also works as an actress and pornographic pinup artist, did particularly well in politics in the 1990s.

And the MSI leader Gianfranco Fini won 47% of the vote for mayor of Rome in 1993.

France

Britain and France also had a neofascist legacy. Both lost their status as great powers, and had to accept immigrants from their colonies. While fascists had little electoral success, they were able to influence public policy on racial issues here.

Collaborators of Vichy France joined anti-communist leagues. As France failed to hold it's colonies in Indochina and Algeria, the Jeune Nation movement called for a corporatist state to remove "stateless" (Jewish) elements, and later terrorizing Left leaders with bomb threats.

This was also inspired by the small shopkeepers and peasants losing out from industrialization in the 1950s. This was expressed by Pierre Poujade, and his anti-parliamentarian and xenophobic “poujadist” movement.

The loss of Algeriers also spawned the creation of the underground terrorist movement, the Secret Army (OAS), focused on destroying “the Left” that had supposedly stabbed them in the back.

Its suppression spawned further groups, like Occident and Ordre Nouveau, especially after the student rising of May 1968.

As European settlers were uprooted from Algeria and went back to France, a new Muslim population now had to be integrated, such as the harkis. This spawned the most successful French radical Right party, the Front National (FN) in 1972.

Britain

The British extreme right also resented colonial immigration, spawning the White Defence League in the 1950s.

This, and the National Socialist Movement, were then supplanted by the National Front in 1967, a blatantly racist anti-immigrant formation.

While they did not have electoral success, they did force traditional parties to take the “immigration issue” seriously.

Socio-Economic Factors

The radical right had an unexpected rebirth in the 1980s and 1990s.

Something akin to fascism was far from dead in Europe as the twenty-first century opened.

It began in 1973, as the older parties seemed to be dying out, like the German NPD, the British National Front, and the French Ordre Nouveau. Other economic shifts were taking place though. Older industries were dying off with the “oil shocks” of 1973 and 79, competing against Asian markets. This led to the first long-term structural unemployment since the 1930s. Industries started having higher education requirements.

Centers of worker support had lost power, like trade unions, Marxist parties, and proletarian neighborhoods. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, people that would have turned to communism before now turned to the radical Right.

The flood of third world immigrants to Europe also increased tension for places already facing unemployment. The demographic of immigrants also changed from southern and eastern Europe to Africa, the Caribbean, India, Pakistan, and Turkey, with visibly different customs, religions, and languages.

The most disturbing was the 1980s “skinhead” phenomenon.

Resentful youths started creating cults of action and violence expressed in fascist symbols, and murderously assaulting immigrants and gays, leading to a surge of incidents. Governments floundered, unable to solve the economic crisis, which encouraged a larger embrace of “anti-politics.” And again, with the Soviet Union gone and the collapse of the communist movement, these people moved to the Right.

Le Pen and the Front National

Jean-Marie Le Pen’s Front National was the first extreme Right party in Europe since 1945 to find the right way to exploit this in 1983. It also was able to maintain this level of support over time. The FN focused intensely on immigration, and related issues around employment, law and order, and cultural defense. It became a broad catch-all party of protest, but without directly threatening democracy, forcing mainstream conservatives to adopt their positions.

This success forced mainstream politicians to make alliances with the FN - Stage Two. However, Le Pen’s movement split in 1998 between him and Bruno Mégret, his heir apparent.

They surged once again due to a groundswell of resentment against immigrants in April 2002. However, he still lost to the incumbent president, Jacques Chirac.

This tactic was adopted by the Italian MSI and the Austrian Freedom Party.

The Rebranding of MSI

In Italy, the Christian Democratics (CD) had enjoyed uninterrupted success since 1948. But when they hit a scandal in the 1990s, some “nonparty outsiders” like Silvio Berlusconi, the richest man in Italy, took advantage, forming Forza Italia.

He formed a coalition with the separatist Northern League and the MSI, now rebranded Alleanza Nazionale (National Alliance).

AN gained five ministerial positions from this, which was the first time a fascist-descendent party participated in European government since 1945. In 2001, Gianfranco Fini, the head of the AN, became vice-premier.

Austria

A similar situation happened in Austria. The socialists and People’s Party (moderate centrist Catholics) shared power for twenty years with the Proporz agreement. Jörg Haider’s Freedom Party served as the only non-communist alternative.

In 1999, they won 27% of the vote, second only to the Socialists’ 33%, receiving six out of twelve ministerial portfolios in a coalition government.

Netherlands

In the Netherlands, the same anti-immigrant frustration led to the rise of the flamboyantly wealthy and gay Pym Fortuyn in 2002.

Fortuyn presented as a right-libertarian, but his vilification of European bureaucracy and Islamic immigrants aligned him with the far Right.

He was assassinated on May 6, 2002 by an animal-rights activist.

Electoral statistics tell us little though. We need to understand the nature of these movements.

Stage Two Fascism

We can ask questions relevant for Stage Two:

Did any of them become bearers of important interests and grievances?

Did significant spaces become available to them in the political system, and were any of them able to acquire the kinds of alliances and complicities among frightened elites that would make Stage Three, an approach to power, conceivable?

Does anything justify our calling these second-generation movements fascist or even neofascist, in the face of their vehement denials?

People that look overtly fascist tend to fail at the ballot box. Successful far Right leaders avoid the language and imagery of fascism.

The MSI is a clear case of this in “normalizing” itself. They proudly proclaimed their legacy with Mussolini until 1994. Then they changed their name to the Alleanza Nazionale (AN), and claimed to be “postfascist.”

In Britain, Colin Jordan’s National Socialist Movement and the National Front were similarly overt. The potential space for fascists was also cut off as Margaret Thatcher moved the Conservative Party to the right. But after some episodes of racial violence in 2001, the British National Party (BNP) was able to see some success.

More were encouraged to normalize after the success of Le Pen and Haider. As more fascists hid their nature, the accusations of “cryptofascism” became more normal. Still, some remarks could not be hidden. Le Pen was frequently anti-semitic, and was fined for belittling Hitler’s murder of the Jews in September 1987. He also struck a female candidate in 1997, losing his eligibility for public office for a year. Haider openly praised the Nazi’s full employment program, and appeared at rallies of SS veterans.

Similarities and Distinctions

These radical Right parties worked as havens for fascists.

Since the old fascist clientele had nowhere else to go, it could be satisfied by subliminal hints followed by the ritual public disavowals.

These parties echoed classical fascist themes:

Fears of decadence and decline

Assertion of national and cultural identity

A threat by unassimilable foreigners to national identity and good social order

The need for greater authority to deal with these problems

While some radical right parties had full authoritarian-nationalist programs, like Vlaams Blok’s “seventy points” and Le Pen’s “Three Hundred Measures for French Revival”. But most are seen as single-issue movements.

Other classical fascist themes, however, are missing from the most successful radical Right parties. The most conspicuous was classical fascism’s attack on free markets and economic individualism, which it remedied with corporatism and regulated markets. Similarly, they miss the attack on democratic constitutions and the rule of law. None propose establishing a single-party dictatorship. They leave to skinheads the open expression of the beauty of violence and murderous racial hatred.

No western European radical Right movement proposed national expansion by war, a defining aim of Hitler and Mussolini. The more frequent calls for changes in borders are secessionist, not expansionist, like Blaam Blok and the Lega Nord. The main exception here is the Balkan nationalists that sought to create a Greater Serbia, Greater Croatia, and Greater Albania.

Belgium

The most important secessionist far Right movement is the northern Flemish-speaking Belgians. Flemish nationalists had collaborated with the Nazis. They emerged again in 1977. Vlaams Blok combined this desire with violent anti-immigrant feelings and “antipolitics.” It was excluded from power only by a coalition of all other parties.

Vlaams Blok became one of the most blatantly xenophobic major radical right-wing parties in western Europe.

Scandinavia

One new space that opened up for the radical Right in the 1970 was the taxpayers revolt against the welfare state. For example, the Scandinavian Progress parties had no hint of fascist style or language, but became a place where the extreme Right felt comfortable expressing anti-immigrant stances.

We must not only compare programs and rhetoric with classical fascism though. We need to keep in mind the great contrast of modern Europe to interwar Europe. Except in post-communist central and eastern Europe, most Europeans have known peace, prosperity, a functioning democracy, and domestic order since 1945. Mass democracy is no longer taking shaky first steps. Bolshevik revolution presents not even a ghost of a threat.

To sum up, while western Europe has had “legacy fascisms” since 1945, and while, since 1980, a new generation of normalized but racist extreme Right parties has even entered local and national governments there as minority partners, the circumstances are so vastly different in postwar Europe that no significant opening exists for parties overtly affiliated with classical fascism.

Post-Soviet Eastern Europe

Russia

No place on earth has harbored a more virulent collection of radical Right movements in recent years than post-Soviet eastern Europe and the Balkans.

Russia was insulated against classical fascism in the Soviet years. However, prior to 1914, it had the Union of Russian Peoples, an Slavophile, antiliberal, anti-Western, anti-individualistic communitarian nationalist party.

Its Black Hundreds killed three hundred Jews in Odessa in October 1905. This was a prominent precursor to fascism.

In the post-Soviet world, this slavophile tradition was revived with groups like Pamyat.

The most successful anti-liberal, anti-Western, anti-Semitic party in Russia was Vladimir Zhirinovsky’s badly misnamed Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) founded in 1989.

While it had great success in 1991 and 1993, it quickly faded due to scandal and Boris Yeltsin’s control on power, followed by his successor Vladimir Putin.

If Putin lost power however, a turn toward an extreme right leader (more competent than Zhirinovsky) seems more likely than a return to Marxist collectivism.

Yugoslavia

Most eastern European radical Right movements have been gratifyingly weak since 1989. But messy democracy, economic, and border constraints give the Right fertile territory. The appeal to join the EU seems to outweigh many of these concerns, which requires at least an imperfect democracy and functioning market.

Post-Communist Yugoslavia was Europe’s nearest postwar equivalent to Nazi extermination policies. After Tito’s death in 1980, and faced with economic decline, the Yugoslav federal state lost its legitimacy. The Serbian president Slobodan Milošević led this destruction, and began exciting crowds about Serbian defeat of Muslims, playing on themes of victimhood and justified revenge.

Serbian nationalism worked as a substitute for communism as a source of legitimacy. Serbian centralization prompted separatism within Yugoslavia for other nationalities. Slovenia and Croatia declared their independence in 1991, and the Serb-dominated sections then seceded from them. The efforts to expel each other led to an increase in violence, murder, arson, and rape. This was called “ethnic cleansing” by the West, although it was more accurately derived from historical, cultural, and religious differences than ethnic ones.

Bosnia declared its independence in 1992, leading to more gruesome ethnic cleansing, as it has many inter-marriages and mingled neighborhoods. Milosevic’s attempt at forming a Greater Serbia was foiled by Croatian armies and NATO intervention in Bosnia and Kosovo. His rule ended in September 2000, after he lost an election, and he was turned over to the UN War Crimes Tribunal.

Serbian nationalism differs from fascism in several important ways for how it gained power, but it also had functional equivalents.

It must be admitted that Serbian nationalism displayed none of the outward trappings of fascism except brutality, and that Serbia permitted relatively free electoral competition by multiple parties. Milosevic’s regime did not come to power by the rooting of a militant party that then allied with the establishment to reach office. Instead, a sitting president adopted expansionist nationalism as a device to consolidate an already existing personal rule, and was supported by a passionately enthusiastic public. On that improvised basis: Milosevic’s Serbia was able to present the world with a spectacle not seen in Europe since 1945: a de facto dictatorship with fervent mass support engaged in the killing of men, women, and children in order to avenge alleged historic national humiliations and to create an ethnically pure and expanded nation-state. While pinning the epithet of fascist upon the odious Milosevic adds nothing to an explanation of how his rule was established and maintained, it seems appropriate to recognize a functional equivalent when it appears.

The horrors of Milosovic distracted from the horrors of the Croatian president Franjo Tuđman, who was no less cruel.

While Serbian nationalism included its anti-Nazi role, Croatian themes embraced Ante Pavelic’s Ustasa, the terrorist nationalists that ruled Hitler’s puppet state of Croatia.

Fascism Outside Europe

Is Non-European Fascism Possible?

Some believe that fascism was a strictly European phenomenon, born from the war between the Great Powers. But if we understand fascism as a response to political and economic crisis, it can be more broadly applied.

If we view fascism as “giving up free institutions,” we’d have to exclude many third-world dictatorships that never had them. Being bloodthirsty is not enough. European colonies are the most likely candidates then.

South Africa

In the 1930s, Nazi-inspired white-protectionists became popular among Boer planters in South Africa. The most obvious is Louis Weichardt’s South African Gentile National Socialist Movement and his Greyshirts, or J. S. von Moltke’s South African Fascists and his orange shirts.

The most successful far-Right movement was the Ossebrandwag (OB) of 1939, building folklore of their “great trek” away from British liberalism.

After 1945, many expected the apartheid system for Anglo-Boer racial unity to turn into fascism. Its destruction by Nelson Mandela turned out to be “one of the most breathtaking happy endings of history (at least for the moment), to the relief of even many Boers.”

Brazil

Latin America came the closest outside of Europe to establishing genuine fascism between the 1930s and 50s. We must be careful here, as many dictators mimicked fascist imagery without being fascist in form.

The closest thing to an indigenous mass fascist party in Latin America was in Brazil with the Ação Integralista Brasileira (AIB) founded by Plinio Salgado, who was directly inspired by Mussolini. The AIB mixed indigenous imagery with more traditional fascist programs of dictatorship, nationalism, anti-Semitism, etc. It peaked in 1934 with 180,000 members.

But it was not the Integralists who ruled Brazil, but the uncharismatic dictator Getulio Vargas.

While he was elected normally, when his term approached his end he set up the Estado Novo, modeled after Salazar’s Portugal, and ruled as dictator until the military coup of 1945. Like Salazar, he did not govern through a fascist party, which he shut down.

A quiet man, he did not have the charisma of a fascist jefe.

Argentina

The Argentinian Colonel Juan Perón matched that figure more, and was a great admirer of Mussolini.

In September 1930, right-wing army officers overthrew Yrigoyen and ended constitutional rule. Originally, General José Uriburu used Mussolini’s corporatist model to deal with the Great Depression. But this “fascist from above” failed to win support, giving way to military-conservative dictatorship, punctuated by fraudulent elections.

When the US joined WW2 in 1941, it pressured Argentina to join the Allies. A military junta formed to resist this pressure and remain neutral.

Juan Perón was an obscure colonel in this junta that took power in 1943. He had asked to be made secretary of labor, and used this control of labor organizations to eliminate socialist, communist, and anarcho-syndicalist leaders. He then merged them into a single state-sponsored worker organization, turning the Confederacion General de Trabajo (CGT) into his personal fiefdom. He gained popular support from this position in settling labor disputes, with anti-establishment rhetoric.

Perón came to power differently than Hitler or Mussolini. He was not leading a military party overthrowing democracy. Democracy had already been abolished. Instead, he had the pressure of mass worker demonstrations. His ambition alarmed his fellow officers in the junta, leading to his arrest in October 1945, but was then released following mass protests from striking workers.

Perón’s dictatorship relied not only on the military then, but the manipulated CGT.

Never mind that the dictatorship never threatened property and did its best to support import-substitution industry, and that Perón’s CGT became more the manager of a working-class clientele than an authentic expression of its grievances.

Still, this gave Perón’s dictatorship a more proletarian character than Hitler or Mussolini’s.

Perón’s dictatorship is the most commonly cited non-European case of fascism.

With its charismatic leader, the Conductor Perón, its single Peronista party and its official doctrine of justicialismo or “organized community,” its mania for parades and ceremonies (often staring Eva, now his wife), its corporatist economy, its controlled press, its repressive police and periodic violence against the Left, its subjugated judiciary and its close ties to Franco, it did indeed look fascist to a World War II generation accustomed to dividing the world between fascists and democrats.

However, recent scholarship tends to focus on non-fascist sources for these elements. Neyond surface appearances, Perón’s dictatorship worked very differently from Hitler and Mussolini. He did not gain power against a democracy in chaos, and even seemed to legitimately win some elections. He lacked the same internal/external enemies - Jews or others - that seem like an essential ingredient of fascism. He had no interest in expansion by war.

His wife Eva Perón also played an important role quite foreign to fascist machismo, as a passionate orator and organizer of women’s vote.

Difficulties with Latin American Dictatorships

Comparing Latin American dictatorships to fascism is dangerous. Their similarities are found in the mechanisms of rule, propaganda, manipulation, and occasionally specific policies. The differences are more apparent when you examine the social and political settings, the relation of the regime to society.

Vargas and Perón both took power from oligarchies, not democracies of established national states obsessed with unity. Neither Vargas nor Perón called to exterminate any group.

In sum, the similarities seem matters of tools or instruments, borrowed during fascism’s apogee, while the differences concern more basic matters of structure, function, and relation to society. The Latin American dictatorships are best considered national-populist developmental dictatorships with fascist trappings, perhaps distantly comparable to Mussolini but hardly at all to Hitler (despite wartime sympathy for the Axis).

If fully authentic fascism did not exist in the most developed Latin American countries, we can look to other cases. The other most common example is the “military socialism” of Colonel David Toro in Bolivia, and his successor German Busch, with their “state syndicalism.”

However, these cases fail for similar reasons, as do other Latin American dictatorships.

Japan

Imperial Japan was the other non-European regime most frequently called fascist, especially from Allied propaganda. Today, most Western scholars consider it non-fascist, while Japanese scholars commonly interpret it as “fascism from above.”

Fascism in interwar Japan can be approached in two ways. One can focus on the influence “from below” of intellectuals and national regeneration movements that advocated a program closely resembling fascism, only to be crushed by the regime. The other approach focuses upon the actions “from above” of imperial institutions. It asks whether the expansionist militarized dictatorship set up in the 1930s did not constitute a distinctive form of “emperor-system fascism.”

Japan had been democratizing in the 1920s. Some junior officers resisted this and encouraged military expansion, like Kita Ikki, who founded secret societies dedicated to assassinations and coups to pursue national regeneration.

The most ambitious attempts was the occupation of Tokyo on February 26, 1936, killing the finance minister and other officials. After this, Kita Ikki was executed. “The emperor himself thus ended what has been called Japanese ‘fascism from below.’”

In June 1937, Prince Konoe Fumimaro became prime minister, supporting the escalation and mobilization for war. Prince Konoe established an overtly totalitarian “New Order” to replace the “Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere.”

Authentic Japanese fascists did appear in the late 1930s. The Eastern Way Society (Tōhōkai) of the black-shirted Seigo Nakano won 3% of the vote in 1942 election. However, Nakano was placed under house arrest, ending his movement.

Prince Konoe also was influenced by the fascist Showa Research Association, but quietly set aside their proposals.

In summary, the Japanese government decided to pick and choose within the fascist menu and adopt a certain number of its measures of corporatist economic organization and popular control in a “selective revolution” by state action, while at the same time suppressing the messy popular activism of authentically (though derivatively) fascist movements.

The militarist expansionist dictatorship of Japan is called fascist because of its alliance between imperial authority, big business, and the military in defense of class interests. But even if they drew from fascist models, the Japanese fascism was imposed by rulers, not a single mass party or popular movement, and disregarded fascist intellectuals. “It was as if fascism had been established in Europe as a result of the crushing of Mussolini and Hitler.”

The American sociologist Barrington Moore proposed a longer-term explanation of military dictatorship in Japan, rooted in the capitalist transformation of agriculture. Britain allowed an independent rural gentry to enclose their estate, forcing out countryside workers into industry. Germany and Japan by contrast industrialized rapidly while keeping traditional landlord-peasant agriculture, who needed to maintain order by force, and their limited markets required external expansion. To this, we could add the strained relation with the Soviet Union, as Russia had invaded Japan.

This model has not been fully convincing to Japan specialists though, as agrarian landlords cannot be shown to play this major role. Japan faced less critical problems than Italy or Germany. It faced no imminent revolutionary threat or a need to overcome some defeat. It also lacked the official party or grassroots movement competing with its leaders.

The Japanese empire of the period 1932-45 is better understood as an expansionist military dictatorship with a high degree of state-sponsored mobilization than as a fascist regime.

Proxy Fascism

Other African or Latin American dictatorships propped up by American or European interests are sometimes called fascist. General Pinochet in Chile, or Seko-Seso Mobuto in the Congo stand out here.

But while odious, they cannot be called fascist, since they did not rest on popular acclaim or were free to pursue expansionism. Mobilizing popular opinion risked turning people against their foreign masters.

United States

The United States has never been exempt from fascism. Antidemocratic and xenophobic movements have flourished in the US with the Native American party of 1845, or the Know-Nothing Party of the 1850s. In the 1930s, fascist movements were conspicuous in the United States.

There was Gerald B. Winrod’s openly pro-Hitler Defenders of the Christian Faith, and their Black Legion.

There was William Dudley Pelley’s Silver Shirts. The “SS” was intentional.

There was Art J. Smith and the Khaki Shirts.

But these movements with exotic looks found few followers.

George Lincoln Rockwell and his American Nazi Party of 1959 to 1967 seemed even more “un-American.”

More dangerous are the movements that employ authentically American themes that are functionally fascist. The Klan revived in the 1920s, spreading virulent anti-Semitism.

In the 1930s, Father Charles E. Coughlin had a radio audience of forty million for his anti-communist, anti-Wall street, and after 1938, anti-Semitic broadcast from his Detroit church. Coughlin supported the Union Party and their candidate William Lemke, who early in 1936 looked like he could overtake Roosevelt.

The Louisiana governor Huey Long also had authentic momentum until his assassination in 1935. But while he was called fascist at the time, he was more accurately a “share-the-wealth” demagogue. He was more focused on individual liberty from plutocrats than the triumph of a national volk.

The fundamentalist preacher Gerald L. K. Smith, who worked with Coughlin and Long and founded the America First party, turned the “Share Our Wealth” message after WW2 against the “Judeo-Communist conspiracy.”

Today a “politics of resentment” rooted in authentic American piety and nativism sometimes leads to violence against some of the very same “internal enemies” once targeted by the Nazis, such as homosexuals and defenders of abortion rights.

For these fringe groups to find powerful allies, the US would need to suffer catastrophic setbacks and polarization.

The US came close to this in 1968 with the anti-war movement and black radials. Since September 11, 2001, civil liberties have been curtailed to popular acclaim in a patriotic war on terrorists. An authentic American fascism would not look like its European model.

The language and symbols of an authentic American fascism would, of course, have little to do with the original European models. They would have to be as familiar and reassuring to loyal Americans as the language and symbols of the original fascisms were familiar and reassuring to many Italians and Germans, as Orwell suggested. Hitler and Mussolini, after all, had not tried to seem exotic to their fellow citizens. No swastikas in an American fascism, but Stars and Stripes (or Stars and Bars) and Christian crosses. No fascist salute, but mass recitations of the pledge of allegiance. These symbols contain no whiff of fascism in themselves, of course, but an American fascism would transform them into obligatory litmus tests for detecting the internal enemy.

Around such reassuring language and symbols and in the event of some redoubtable setback to national prestige, Americans might support an enterprise of forcible national regeneration, unification, and purification. Its targets would be the First Amendment, separation of Church and State (creches on the lawns, prayers in schools), efforts to place controls on gun ownership, desecrations of the flag, unassimilated minorities, artistic license, dissident and unusual behavior of all sorts that could be labeled antinational or decadent.

Black Nationalism

The assertions of some African-American nationalists also have a “regrettably fascist ring,” according to Henry Louis Gates Jr. This usually involves some narrative of “the redemptive power of Afrocentricity” against “European decadence.” This is reflected in the classifications of Professor Leondar Jeffries of “sun people” (Africans) and “ice people” (Europeans), and his conspiracy theory that “ice people” have always tried to exterminate the “sun people.” If we added to this an exaltation of remedial violence against external enemies and internal slackers, we get pretty close to fascism.

However, this movement within a historically excluded minority would have little chance at genuine power.

But such a movement within a historically excluded minority would have so little opportunity to wield genuine power that, in the last analysis, any comparison to authentic fascisms seems far-fetched. A subjugated minority may employ rhetoric that resembles early fascism, but it can hardly embark on its own program of internal dictatorship and purification and territorial expansionism.

Religious Fascism

Can religion serve as a function equivalent of fascism? Was Iran under the Ayatollah Khomeini fascist? What about Hindu fundamentalists in India? Al-Qaeda among Muslim fundamentalists? The Taliban in Afghanistan? Protestant fundamentalism in America?

European fascism has typically been more anti-clerical, pulling from other radical anti-clerical traditions. But even Europe has seen religious fascisms with the Falange Espanola, Belgian Rexism, the Finnish Lapua Movement, and the Romanian Legion of the Archangel Michael. This is even if we exclude the Catholic authoritarian regimes of Spain, Austria, and Portugal. Religious identity may be even more powerful than national identity. This can be seen with some Orthodox Jews, and fundamentalist Muslims and Hindus.

The main objection to calling movements like al-Qaeda or the Taliban fascist is that they are not reactions against a failing democracy. They are not being convinced to “give up free institutions.”

Israel

This raises the incredibly ironic possibility of an Israeli fascism, especially in its relation with Palestine and the intifada.

Israeli national identity is heavily tied up with the promise of human rights that have been so long denied to the Jewish diaspora. This works as something of a barrier to them giving up free institutions, even while fighting against Palestinian nationalism.

However, this is weakened by two trends. Firstly, hardening in the face of Palestinian intransigence. Secondly, a shift within the population away from European Jews with a democratic tradition, toward North African or Near East Jews without one. This hardening can be seen after the violence of the second intifada of 2001.

By 2002, it was possible to hear language within the right wing of the Likud Party and some of the small religious parties that comes close to a functional equivalent to fascism. The chosen people begins to sound like a Master Race that claims a unique “mission in the world,” demands its “vital space,” demonizes an enemy that obstructs the realization of the people’s destiny, and accepts the necessity of force to obtain these ends.

Conclusion

If we accept that fascism is not uniquely European, the possibility for fascism remains. Indeed, it seems even more likely as more failed experiments with democracy have taken place since 1945. Stage One levels of fascism can be found in all major democracies. But is Stage Two possible, becoming rooted and influential?

We need not look for carbon copies of Nazi memorabilia. Hard-core neo-Nazis are also capable of destruction, and violence. But so long as they are not mainstream and power is not shared, they remain more a criminal threat than a political one.

The extreme Right movements that have learned to moderate their language and avoid overt fascist symbols to appear “normal” are the greater threat. But the way we recognize fascism is by how it worked, not by its symbols.

Some warning symbols are obvious, like extreme nationalist propaganda and hate crimes.

We can find more ominous warning signals in situations of political deadlock in the face of crisis, threatened conservatives looking for tougher allies, ready to give up due process and the rule of law, seeking mass support by nationalist and racialist demagoguery. Fascists are close to power when conservatives begin to borrow their techniques, appeal to their “mobilizing passions,” and try to co-opt the fascist movement.

Armed with this knowledge, we may be able to better detect real fascism when it comes along.