Introduction

Paxton’s Anatomy of Fascism can be read here. Read my notes on chapter five here.

This is a particularly grim chapter that covers both the Holocaust and World War II.

Having thoroughly established how fascism functions in the previous chapters, we see here an interesting mix of examples of how it could turn out. The tension within fascist governments that are so defining of it eventually leads to it burning out in radicalism or conservatives reasserting control. In Spain and Portugal, frequently thought of as fascists, we do see clear fascist movements in power, but which were almost entirely dominated by conservatives so that they became a more traditional form of authoritarianism.

Hitler’s domination over the conservatives by contrast allowed for constantly escalating radicalism, the most horrific being the Holocaust itself. We even see that weird tension come out in ways for how it came to be, with the fascist underlings not necessarily getting direct orders but trying to outdo each other with tacit approval for enacting their murderous fantasies.

Mussolini seems like a more mixed bag. The stronger conservative institutions in his country, especially the King and the Catholic Church, never allowed him to get the ‘total’ of his promised totalitarianism. He was removed from power by these forces. When the Italian fascists were given a puppet state by Hitler though, they went through their own kind of quick radicalization.

Chapter 6: The Long Term: Radicalization or Entropy?

Fascist regimes could not settle down once in power. The fascist leaders made dramatic promises, so needed sweeping solutions with a lot of spectacle. Without momentum, they risked decaying into a more tepid authoritarianism, becoming “normalized.” Fascist regimes do not necessarily succeed in maintaining this momentum, and may even “normalize” themselves on purpose.

Normalization in Spain

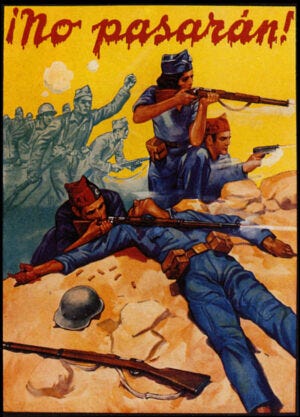

For example, the Spanish dictator General Francisco Franco is often taken as a fascist, due to his conquest in the Spanish Civil War with the support of Mussolini and Hitler.

The Spanish Republicans and Anarchists he fought against were the first and most emblematic antifascist crusade.

Franco won in March 1939, and seemed pretty fascist. Soon after, he began a bloody repression, killing as many as 200,000 people. He sealed off his nation economically. He was extremely hostile to democracy, liberalism, secularism, Marxism, and Freemasonry. He signed the Anti-Comintern Pact with Mussolini and Hitler. In 1940, he seized Tangiers from French Morocco. He seemed set to become a full-scale partner of the Axis.

But whenever Hitler tried to get him to act, he set his price unattainably high. Hitler hated dealing with him. Franco wanted peace and quiet after the Spanish Civil War, not fascist dynamism.

He did have a fascist party, the Falange. But it lacked the “parallel structures” to become an autonomous power, and had no share in policy making. The Falange’s charismatic leader, Jose Antonio Primo de Rivera, was eliminated. This established the preeminence of the established elites and the “normative state.”

Franco’s also had tight control over Primo de River’s successor, Manuel Hedilla. This further reduced fascist influence.

The Falange was submerged into a more broadly authoritarian pro-monarchy group, the “Falange Espanola tradicionalista y de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional Sindicalista” (FET y de las JONS). When Hedilla tried to reassert authority in April 1937, Franco had him arrested. The Falange devolved into the Movimento. In 1970, even its name was abolished.

Spain had no visible fascist coloration, becoming mere authoritarianism.

Normalization in Portugal

Portugal was an even more clear example. The government of Portugal had been overthrown in a military coup in 1926. This set up Antonio de Oliveira Salazar as dictator, an ultra-catholic economics professor.

But his dictatorship was even more quiet than Franco’s. While Franco absorbed the fascist party, Dr. Salazar abolished Rolao Preto’s blue-shirted National Syndicalists in July 1934.

When civil war broke out in Spain in 1936, Dr. Salazar experimented with a “New State,” borrowing fascist elements. He had a corporatist labor organization, youth movement, and the blue-shirted Portuguese Legion.

Yet he rejected fascist expansionism, and remained neutral in World War 2. He wanted to avoid conflict so much, they even avoided military or industrial expansion until the 1960s. He explicitly avoided totalitarian domination of life outside politics.

So again, we have the elements of fascism, but then a conscious choice to move towards conservative authoritarianism.

Radicalization in Germany

Nazi Germany is at the other extreme, entirely rejecting conservatism for full radicalization.

The Nazis had near limitless freedom due to their victorious war in the east. In Poland and the western Soviet Union, Nazi radicals could carry out their fantasies of racial cleansing.

While the potential for radicalization exists in all fascisms, circumstance may allow for greater expression.

Radicalization and Normalization in Italy

Radicalization was present in Fascist Italy, but with an aging party and greater conservative drag, it went a different direction

Mussolini promised totalitarianism, but only gave radicals control when he benefitted. He preferred stability to adventure. This is seen with his pacification pact, his “normal” first two years in office, his curbing of the ras, his refusal to challenge the monarchy or Church, and his alliance with conservatives.

Mussolini’s economic policy conformed during those early years to the laissez-faire policies of liberal regimes. His first minister of finance (1922-25) was the professor of economics (and party activist) Alberto De Stefani, who lowered government spending and balanced the budget. It is true that De Stefani, committed not only to free trade but also to the fascist ideal of stimulating productive energy, made some businessmen angry by cutting such import duties as the one protecting expensive locally produced beet sugar. In general, however, he displayed “an unmistakable pro-business bias.”

So Mussolini would promise radicalism, only to push things back to normality. This cycle was seen again with the murder of the socialist leader Giacomo Matteotti. After that, Mussolini only seized power with pressure from his party radicals, as seen in chapter 4.

At first, it seemed like he was going for the “totalitarian” state, appointing extreme Fascist militants like Roberto Farinacci as secretary. But then he fired Farinacci a year later, replacing him with the less radical Augusto Turati.

Mussolini preferred less radical appointments in general. The Italian police were entrusted to the professional civil servant Arturo Bocchini. Fascist Italy did not go down the Himmler model.

Operating the all-important police force on bureaucratic principles (promotion of trained professionals by seniority, respect for legal procedures at least in nonpolitical cases) rather than as part of a prerogative state of unlimited arbitrary power was Italian Fascism’s most important divergence from Nazi practice.

In 1928, Mussolini removed the syndicalist Edmondo Rossoni as leader of the Fascist trade unions. This ended any real labor representation or real syndicalism in Fascism, and the “Corporate State” simply reinforced the power of employers.

Mussolini’s biggest move toward normalization was his 1929 Lateran Pact with the papacy. The pact forbade Catholic political activity in Italy, but it let them grow their youth and worker association. The Catholic Church would outlast Fascism in Italy, and with this base, they secured the postwar rule of the Christian Democratic Party.

Mussolini’s fascism then is marked by a retreat into more traditional authoritarianism. He grew the power of the monarchy, organized business, the army, and the Catholic Church, independently from the Fascist Party or State.

Still, Mussolini’s aging movement needed some outlet, which led to the war of aggression in Ethiopia. This led to a spiral to radicalization with the “cultural revolution” of 1936-38, the European war in 1940, and the puppet republic of Salo under Nazi occupation in 1943-45.

What Drives Radicalization?

The “intentionalist” view was driven by Mussolini’s apparent vacillation between normalization and radicalization. But the leader’s intent means little unless people obey him.

The “structuralist” view was driven by Hitler’s indolence. They argued the impulse for radicalization comes from below, and the leader just provides cover. But we don’t need to deny the input of leaders to recognize that fascism, unlike other authoritarian models, is characterized by the dynamism and excitement of its base.

It was dangerous for fascism to abandon this radicalism, or else the leader loses power to the independent old elites. The fascist party is a source for powerful radicalization. Fascism needs a popular movement, both to achieve power and to run parallel organizations. This means the militants need rewards to remain loyal, which disrupts the alliance with conservatives.

Hitler solved this problem with the Night of Long Knives in June 1934, but he was never in perfect control.

Mussolini was also willing to kill, but he was only willing to kill his party lieutenants under German boot in 1944. Mussolini had to give in to his party’s demands on occasion. Other times, he tried to divert the radicals in positions he controlled, like with Farinacci, or sent them off to Africa, like with Italo Balbo.

Hitler also had an early laissez-faire period, naming the conservative Lutz Graf Schwerin von Krosigk his first minister of finance.

For a time, he left diplomacy and the army to the hands of professional soldiers. But his drive to shrink the normative state and expand the prerogative state was stronger than Mussolini’s, and he had better control of his party after June 1934.

The chaotic rule of fascism might also be key to its radicalism. Contrary to propaganda, fascist regimes are not well-oiled machines. Hitler had his agencies and lieutenants compete to do the same task, resulting in feudal struggles.

Hitler spent as little time as possible working until the war, preferring to give grand hateful speeches. His underlings would then compete to complete his fantastical visions, as he arbitrated between them and rewarded projects he liked. This pushed on Nazi radicalization.

Mussolini however refused to delegate out of suspicion. He was committed to doing the drudgery of government himself. This caused more inertia than radicalization.

War is the most clear source of radicalization. This works in a kind of cycle. World War I led early fascist movements to exalt violence, and gave them the necessary discipline and energy. War creates need for, and public acceptance of, more radical measures. Mussolini and Hitler deliberately chose war as a step to realize the full potential of their regimes.

Revisionism forced scholars to examine if Hitler really wanted war. They concluded that, while Hitler might not have wanted a long war on two fronts, he did want local, short, victory in Poland, and every part of the Nazi regime was designed for war.

Mussolini thought war was the sole source of human advancement. Mussolini began preparing for war less than a year after becoming prime minister, bombing Greece after the Corfu incident. The Duce began preparing to invade Ethiopia in 1933-34.

This decision aligned him with Hitler and against Britain and France, who did not want Italy in Africa. It was motivated not only out of Italian imperialist ambitions, but a need to revive Fascist dynamism after a decade in power.

When WW2 approached, Mussolini wanted to negotiate a settlement, but could not stand by forever. When Germany seemed to be winning, he rushed to join the war on France in June, 1940. Perhaps he thought it would give him more power. And he had preached the virtues of war too long to hang back. He later declared war on Albania and Greece, places of no strategic import, for similar reasons and to look like he was waging his own war “parallel” to Hitler.

Glorifying the military is common to non-radical authoritarian regimes too. This is seen with Franco in Spain, Marshal Petain in Vichy France, and even Salazar in Portugal. But there is a difference with fascists. Authoritarians like pomp, but little fighting, to prop up the status quo. Fascists need to conquer new land for their “race.”

Fascism is not a mere war government. All governments need to adapt to the needs of war. Many give up material comforts and liberties when the enemy is at the gates. But with fascist regimes, a fanatical minority in the party find opportunity for radical expression, beyond any strategic need.

Hannah Arendt emphasized the fragmentation and atomization of Nazi society, which might be inaccurate early in these regimes, but is more accurate for their radicalization. In newly conquered territories, inexperienced fascist radicals were placed in charge, and essentially left to improvise how to rule a conquered people.

Trying to Account for the Holocaust

The outermost reach of fascist radicalization was the Nazi murder of the Jews.

Good accounts of the Holocaust must have two qualities. Firstly, it must account for not only Hitler’s obsessive hatred of Jews, but the thousands of subordinates that followed him. Secondly, it must recognize that the Holocaust developed step-by-step, working from lesser acts to more heinous ones. Local vigilantism and murderous state policy fed off each other.

The first phase was segregation. The internal enemy was set apart, suppressing their rights. This began in 1933 as street action when Hitler took power. The regime channeled this into an official one-day boycott on April 1, 1933. The Nuremberg laws of September 15, 1935 then banned intermarriage and annulled Jewish citizenship.

It paused this violence in 1936 to save face during the Olympics.

Street violence erupted again in November 1938 with Kristallacht (The Night of Broken Glass), burning synagogues and smashing shops.

Segregation reached its peak with marking Jews. First in occupied Poland (late 1939), then in the Reich (August 1941), all Jews had to wear a yellow Star of David.

The next stage was expulsion. The annexation of Austria in March 1938 increased the number of Jews in the Reich. It also let the Nazis deal with them more harshly. The conquest of western Poland in September 1939 brought in more Jews, and more harsh measures. No Nazi-ruled area wanted to take them. While many wanted to dump them in Poland, the Nazi governor of Poland Hans Frank convinced Hitler not to.

This was further complicated by Himmler’s plan to bring in 500,000 ethnic Germans from these other territories. Some Nazis came up with plans to send the Jews to Madagascar as a solution. The Nazis hoped invading the Soviet Union in June 1941 would make this easier. While it would bring in more Jews, it would also give a lot more land to send them to.

Expulsion remained the official solution until late 1941. Nazi-occupied territories had a lot of individual leeway for policy, e.g. ghettoization, forced labor, resettlement, etc.

Mass murder began as a local policy, as eastern Polish Nazis moved from killing Jewish men for “security” reasons to mass murder in August-September 1941. The infamous Wannsee Conference, where high-level Nazis presented the “final solution,” in this respect was just continuing on coordination of these local efforts, rather than a new policy.

When exactly Nazi policy shifted from expulsion, to killings for “security” reasons, to annihilation is still debated. It is not clear if we should focus on Hitler or his underlings. The lack of any direct order from Hitler for the annihilation troubles the “intentionalist” model, but perhaps unnecessarily. No serious scholar doubts Hitler’s central responsibility. His hatred of Jews was well known, and he was briefed regularly. He likely gave a verbal command at one point. Some think it can be pinpointed to a secret speech to high-ranking officials on December 12, 1941, after the US joined the war.

Hitler would thus be fulfilling the threat he made in a speech on January 30, 1939 - that if the war became worldwide, the Jews were to blame and would pay (Hitler believed Jews controlled American policy).

If we focus on his underlings, some already crossed this line before the late summer of 1941. This would not have been possible without wide-scale Jew-hatred. But this does not tell us why it was crossed in some places instead of others.

The best explanations show this as a build-up of previous issues. Two kinds of developments help explain the readiness to kill all Jews. Firstly, a series of “dress rehearsals” that lower inhibitions and hardened personnel.

The first dress rehearsal began with euthanizing the incurably sick or insane German, according to Nazi eugenics theory, encouraged by the war. The T-4 program killed more than 70,000 people between September 1939 and 1941. Some people involved were sent off to the east, where the practice was applied to Jews.

The second dress rehearsal began with the Einsatzgruppen of the SS, charged with killing the cultural elites of invaded countries. The “Commissar Order” ordered the killing of all Community Party cadres and jewish leadership, which the Nazis saw as identical. They then played a large role in the annihilation.

The third dress rehearsal was the intentional death of millions of Soviet POWs. Here was the first use of mass killing by Zyklon-B at Auschwitz on September 3, 1941.

Secondly, a series of crises and emergencies which made Jewish presence seem unbearable. The failure to conquer Moscow stopped the ability to send Jews further east. The German invaders also had a shortage of food supplies. They had fully intended to live off pillaged resources from the area, knowing this would mean starvation for the locals.

Nazis were delusional enough to also think Jews and “Gypsies” posed a security threat to German forces. The arrival of ethnic Germans also created a need for new spaces to be opened up. With these building problems, Nazi administrators tried “intermediary solutions.” Ghettos proved to incubate disease, which the clean Nazis detested. The other was the failed plan to send the Jews to Madagascar, East Africa, or the Russian heartland. The failure of these solutions paved the way for the final solutio.

The first mass executions were by gunfire. The process was slow, messy, and psychologically stressful on the Nazis. More efficient methods of murder were needed. This led to the Gaswagen, specially prepared vans which were then filled with exhaust fumes.

These were first used on the mentally ill in Poland 1940. By fall 1941, thirty such vans were used to kill Jews in occupied Russia. Fast techniques were developed in spring 1942, with fixed installations at six camps in Polish territory. Most used carbon monoxide, but some (like Auschwitz) used the more efficient Zyklon-B.

These death factories accounted for 60% of Jews murdered by Nazis during WW2. They were built outside of the reach of the German normative state. The Nazi parallel organizations set up their own system in occupied territories, outside the reach of the normative state.

Bureaucratic regularity and morals were set aside for the whim of party radicals. Here they could indulge their darkest impulses, and the Fuhrer rewarded this initiative.

The Nazis did not murder Jews to gratify public opinion, as they hid their actions from the German people and foreign observers. Reports referred to the killings with euphemisms, like Sonderbehandlung (“special handling”), and hid their tracks.

But there was no particular effort to do so on the eastern Front from the troops, who often participated. Some even took photos and sent it back to their families and girlfriends.

The knowledge that horrible things were being done to the Jews was fairly widespread. So long as it was not done in front of them though, it was met with public indifference.

In the end, radicalized Nazism lost even its nationalist moorings. As he prepared to commit suicide in his Berlin bunker in April 1945, Hitler wanted to pull the German nation down with him in a final frenzy. This was partly a sign of his character - a compromise peace was as unthinkable for Hitler as it was for the Allies. But it also had a basis within the nature of the regime: not to push forward was to perish. Anything was better than softness.

Italian Radicalization: Internal Order, Ethiopia, Salò

The final form of Nazi Germany is the only authentic example of fully radicalized fascism. Italian Fascism had the same forces driving it to the extreme though. Mussolini was torn between his radical party, his personal desire for order, and his self-promoted image of a revolutionary hero.

In the 1930s, to distract from the Depression and rejuvenate his movement, Mussolini went on his most radical period. He adopted an aggressive foreign policy, called for rearmament, and predicted “the twentieth century will be the century of Fascism.” By 1934, he was preparing to invade Ethiopia. He launched his invasion on October 3, 1935, on a flimsy pretext from a minor skirmish on a remote desert island. The invasion took more Italian effort than foreseen, but he declared King Victor Emmanuel III the Emperor of Ethiopia on May 9, 1936.

The war gave occasion for a lot of nationalist theater. Wedding rings were collected from Italian women to pay for the war. The party presence was strong in the conquered territory, and Fascist youth and leisure organizations were set up. This also accompanied a “cultural revolution” and “totalitarian leap” in Italy.

Party secretary Achille Starce started instituting “Fascist customs,” such as replacing the formal you (“lei”) with the informal and comradely “tu” or “voi,” the Fascist salute replacing handshake, and armies marching with the passo romano to be distinct from the Nazi goose step.

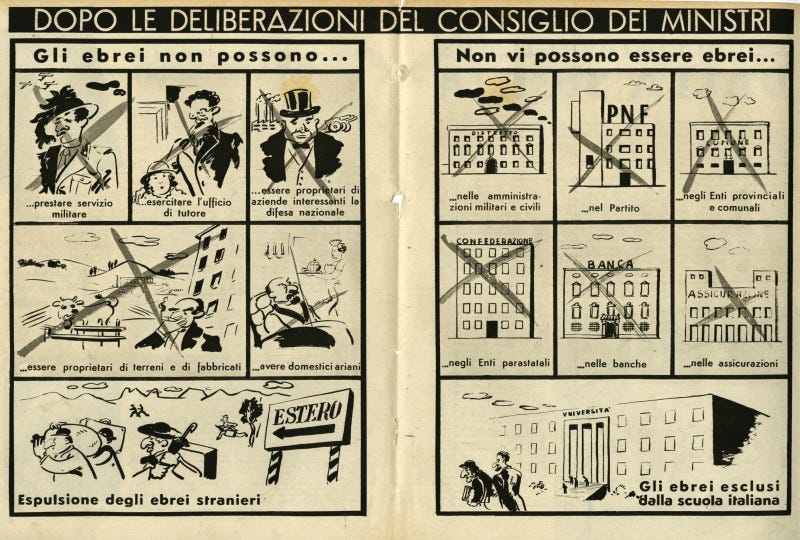

The most striking step in Fascist radicalization was it's antisemitic legislation in the 1930s. In July 1938, the "Manifesto of Fascist Racism" forbade interracial marriage, and excluded Jews from government and university positions. These largely copied Nazi Nuremberg laws.

Many think this was just to please Hitler. Italy has a small Jewish population that was well integrated. As we saw, Mussolini even had early Jewish supporters. But there was some native Italian anti-Semitism too. Racial discrimination was already policy in Italian colonies. Ethiopia even seemed to have its own apartheid.

Catholics had an ambiguous attitude to Jews. The Catholics opposed biological racism, but the Jews were still seen as the people that killed Christ. The church raised no objection to non-biological racism.

The 1938 legislation was unpopular, but there was enough support that it held firm.

Mussolini joined WW2 late, and it brought him neither victory nor spoils. His "parallel war" led only to defeat and humiliation. Germans also dreaded the start of WW2, but Hitler's success turned things around. The Italian support quickly burst.

Mussolini's final days also brought radicalization, but only in northern Italy. Some fascists were ready to get rid of Mussolini and make peace. The Allies landed in Sicily on July 10th, 1943.

The Fascist Grand Council voted to restore full authority to the king on July 25th. The king dismissed the Duce on the same afternoon.

This should have put an end to Mussolini's charisma. However, on September 12th, a German SS raid liberated him from captivity from a ski resort.

Hitler reinstated him as dictator of Salò, a German puppet, called the Italian Social Republic.

While this was a mere footnote in history, it does give us a look at Fascism freed from the church and industrialists. They ramped up populist national socialism. They called to "socialize" economic sectors needed for self-sufficiency. It promised to turn over unproductive farms to the farmhands, and leave only property that results from personal saving. But it never had the power to put any of this into effect.

The main real effect was make it's police murderous in an Italian civil war. It was also here where Fascists took anti-Semitism more seriously, and started putting Jews in camps. The Salò Fascists sought revenge against the Fascist Grand Council, and killed what members they could.

Mussolini lost all support as the Allies approached in April 1945. Italian partisans found him and killed him on April 28th, fleeing in the back of a German truck, then strung up his corpse.

Final Thoughts

Fascism is most distinct at this stage. While any regime can radicalize, the depth and force of the fascist impulse to unleash destructive violence, even to the point of self-destruction, sets it apart. Since only the Nazi regime fully radicalized though, comparison is difficult.

A tempting candidate is Stalin's Soviet Union. They both suspended law and due process in the name of "history." However, fascism is different from Stalin's radicalism. Fascism idealizes violence in a way the Soviets did not, presenting it as the virtue of the master race. Instead of their parallel organizations replacing established elites, fascists worked with them.

Expansionist war is at the heart of radicalism. With fascism, this takes a unique form, since it is not the established conservative army exercising control, but the parallel organizations, giving party radicals free reign. It would be unthinkable for a traditional military dictatorship to tolerate the incursions of amateurish party militias into military spheres that Hitler - and even in Ethiopia, Mussolini - permitted.

Hannah Arendt's Origins of Totalitarianism fails in its analysis of early fascism, but fits here. An obsessed minority is able to carry out its passionate hatred without calculations of interest. In the outposts of the empire, away from their bourgeois allies, fascism can recover its early days of face-to-face street violence.

Fascism is only able to do this with the continued complicity of the state services and large sections of the socially powerful. Fascist radicalism is not persuasion to make people give their all to the war effort. It often goes against these interests even.

Finally, radicalization denies even the nation that is supposed to be at fascism's heart. In the end, fanatical fascists prefer to destroy everything in a final paroxysm, even their own country, rather than admit defeat.

Prolonged fascist radicalism has never been witnessed. It's hard to even imagine it as possible. The succession of fascist leaders remains a hypothetical problem. More likely is the decay into traditional authoritarianism.

Fascism is destabilizing. In the long run then, it is not even the solution frightened conservatives and liberals hoped for. The fascist regimes of Italy and Germany drove themselves off a cliff. Mussolini could not hold his grip on the people without joining Hitler's war. Hitler never stopped imagining further conquests.

The fascisms we know seem doomed to destroy themselves in their headlong, obsessive rush to fulfill the "privileged relation with history" they promised their people.