Introduction

Paxton’s Anatomy of Fascism can be read here. Read my notes on chapter four here.

This is an especially interesting chapter because it focuses on the aspects of fascism that seem most unique. While authoritarianism and dictatorship has existed as far back as states have been a thing, a distinguishing feature of fascism is this constant tension and “dual state” system that make it almost like an aborted revolution. Parallel organizations that might be used by socialists to replace the state or capitalism are instead integrated in an unstable alliance.

“Unstable” really is the key word here. There is constant competition between the fascist leader, the party, the state, and conservative centers of power. This competition seems to account for a lot of the strange radicalism and energy beneath fascist activity, who could not settle. A fascist leader who relied almost nakedly on charisma for holding onto power needed to constantly impress their radical party members without wrecking business prospects.

This conflict, especially between the fascists and the conservatives, seem to dictate a lot of the long-term trajectory of fascism. If the fascist side wins out, it is pushed further and further into self-destructive radicalism. If the conservatives win out, the fascist radicals cannot get their way and a more traditional authoritarian system asserts itself. This aspect is covered more in the next chapter though.

Chapter 5: Exercising Power

The Nature of Fascist Rule: “Dual State” and Dynamic Shapelessness

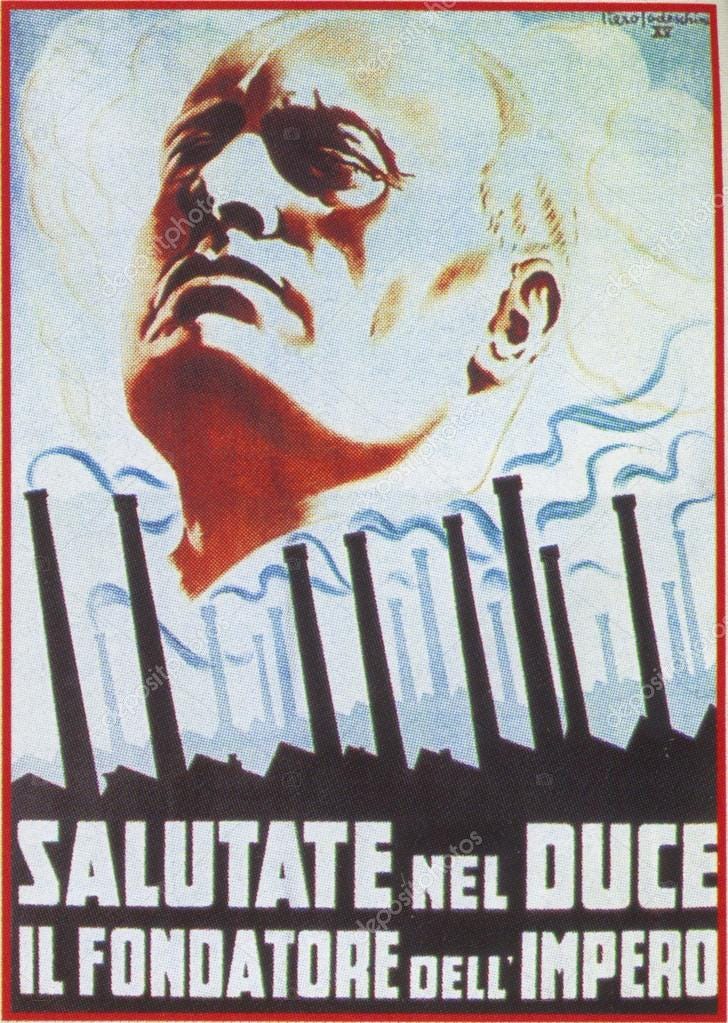

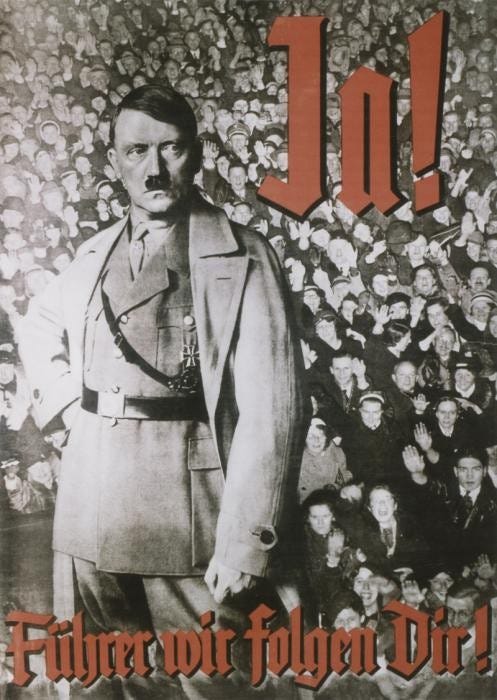

Fascist propaganda wants us to think the leader rules alone, and has been very successful at convincing people of this.

This was reinforced by Allied wartime propaganda of the Nazi juggernaut, which also focused on the enemy leaders as constructing the entire problem.

Postwar German and Italian conservatives used this as a convenient excuse, pretending to be victims of the fascist leader rather than their accomplices.

But no dictator rules by himself. Fascist leaders need the cooperation of decisive agencies like the military, police, judiciary, and senior civil servants.

Some degree, at least, of obligatory power sharing with the preexisting conservative establishment made fascist dictatorships fundamentally different in their origins, development, and practice from that of Stalin.

Consequently we have never known an ideologically pure fascist regime. Indeed, the thing hardly seems possible.

The reliance of fascist regimes on conservatives has been well noted. For example, the contemporary German social democrat refugee Franz Neumann, the moderate liberal Karl Dietrich Bracher in the 1960s, Martin Broszat, and Hans Mommsen. For Italy, this was even more obvious. Gaetano Salvemini noted the “dual dictatorship” of Duce and king. This is also noted by other prominent historians of fascism like Alberto Aquarone, Wolfgang Schieder, Jens Petersen, and Massimo Legnani, as well as by the fascist Emilo Gentile.

Fascism is not static. It is in constant tension with their conservative allies.

Conservatives tend to pull back toward a more cautious traditional authoritarianism, respectful of property and social hierarchy; fascists pull forward toward dynamic, leveling, populist dictatorship, prepared to subordinate every private interest to the imperatives of national aggrandizement and purification. Traditional elites try to retain strategic positions; the parties want to fill them with new men or bypass the conservative power bases with “parallel structures”; the leaders resist challenges from both elites and party zealots.

The course of the fascist regime is determined by this balance of power. In Italy, conservatives had the upper hand, and the regime decayed toward more traditional authoritarian rule. In Germany, fascists had the upper hand, and it radicalized into unbridled party license.

Ernst Fraenek described this tension in Nazi Germany as being between the party (the “prerogative state” of traditional, bureaucratic civil servants) and the state (the “normative state” of party parallel organizations).

This model helps to explain strange mixtures of legalism and arbitrary violence in Nazi Germany. For example, some Jewish victims were able to successfully sue individual Nazi attackers, even while state violence was mounting.

Hitler never abolished the constitution of the Weimar Republic, even while he refused to be bound by it himself. Instead, he enjoyed the broad extralegal power to repress any perceived Marxist “terror” after the Reichstag fire. Over time, the prerogative state took over the normative state, especially after the war began. It barely existed in occupied Poland or the Soviet Union. This does not excuse the normative state. It could be just as cruel and arbitrary. People are wrong to distinguish the “correct” professional army and the criminal SS.

Fascist Italy had a similar dual state structure, but Mussolini conceded far more power than Hitler, and placed the state, not the party, at its center. Mussolini had less leeway, less drive, and less luck than Hitler. King Emmanuel III was around the entire time, and eventually deposed him in July 1943. Mussolini also had more insubordinate fascist chieftans to deal with, acting as rivals. Still, Mussolini had important prerogative state functions. It had a secret police (the Organization for Vigilance and Repression of Anti-Fascism, or OVRA), a controlled press, economic baronies like the IRI, and African fiefdoms where party chiefs could kill indigenous people on a whim. The war strengthened this prerogative state.

The tensions in fascist regimes go beyond simply the normative state vs the prerogative states. They also sought to replace other power centers, like labor unions, youth clubs, and other professional associations.

The Nazis even wanted to impose a “German Christian” bishop for their own doctrine of Protestantism.

These areas that survive totalitarian dictatorship are sometimes called “islands of separateness.” For example, Catholic parishes had enough organizational resilience and loyalty to survive infiltration. The Nazis tried to overcome this with “Gleichschaltung”, i.e. coordination or leveling. But this program was also subverted to the ends of these other organizations. They used the secret police for their own private purposes, and Nazi officials still had some loyalty to their university fraternities.

Success was slower in Fascist Italy. Only the labor unions, political parties, and media were fully controlled. But the Catholic Church was not, having its own youth movement and schools.

Fascist regimes then have a four-way tension:

The fascist leader

The fascist party (Demanding jobs, wars, policies)

The state apparatus (Police, military, governors, etc.)

Civil society (Conservatives, business leaders, churches, “social power” holders)

All four groups are held together in the fascist regime since none can get rid of the others without ceding power to the Left in the process. Conservatives did not get rid of the fascists out of fear of the Left electoral victories. The fascist leaders need the military and economic base the conservatives controlled. They also need their noisy parties to do that, even while they undermine the leader’s power.

No contender could destroy the others outright, for fear of upsetting the balance of forces that kept the tandem in power and the Left at bay.

Within this tension, the fascist parallel organizations play an important, but ambiguous, role. They allow the fascist leader to out-flank the conservative organizations. But they also allow the fascist party autonomy against the leader.

Fascist Italy set up these parallel structures to gain power. But once in power Mussolini declared them subordinate to the state.

The Duce had no intention of letting the ras push him around again.

Italian Fascism had the most success here with its leisure clubs.

The Nazis had a similar strategy of parallel organizations. The party had its paramilitary (the SA), courts, police, youth movement, and foreign policy branch.

But once the Nazis took power, these agencies threatened to overtake the state institutions. The political police became detached from the Interior Ministries of the German states to become centralized under Heinrich Himmler’s Gestapo.

Duplication of traditional power centers by parallel party organizations was a principle reason for the already noted “shapelessness” and the chaotic lines of authority that characterized fascist rule and set it apart from military dictatorship or authoritarian rule.

The fascist rise to power brought in opportunists. People joined the party just to rise in the ranks. In Italy, this seemed to temper Fascist power more than it radicalized the population. This also happened in Nazi Germany, even if party positions were more closed off.

In the struggle for predominance, either conservatives or fascists can gain an upper hand. Hitler was able to subject his allies to many unwanted policies, but he was only able to really override others when the war became total in 1942. By contrast, the conservative institutions had much better control over Mussolini. The Catholic Church got extremely favorable treatment from the atheist Mussolini. He also abandoned his syndicalist allies to favor businessmen interests. This control was so strong that they ultimately removed him from power as the Allied Army advanced on Italy.

Still, fascist leaders enjoyed a rare kind of supremacy. Their power did not rely on election or conquest, but charisma. Fascist leaders appeal to a mysterious direct connection to the “volk” or “razza.” Charisma is common for other leaders too, of course, but fascist leadership is more nakedly dependent on charisma. This may explain why fascist regimes have never successfully passed power to a successor.

This reliance on charisma also helps explain why Hitler’s indolence increased his control, rather than weakening him. At the same time, fascist leaders can very quickly fall from grace if they begin to lose, as Mussolini found out.

This all shows why focusing on the leader’s will too much is mistaken. Fascism seems more like a kind of “polyocracy,” with multiple centers of power. Studying the complexities of fascist dictatorship also carries two risks:

It is hard to account for the “demonic energy” this tension produced, rather than gridlock

It can lose sight of the leader’s supremacy

This is reflected in the historical debate between “intentionalist” and “structuralist” theories of fascism. Intentionalists focused on the leader’s will. Structuralists or functionalists emphasized links with the state and society. Intentionalism works better for the bureaucratic Mussolini, but less for the neglectful and often absent Hitler, as he held lavish parties, slept in, and so on.

There must be some mixture between intentionalism and structuralism.

The most convincing work established two-way explanations in which competition among midlevel officials to anticipate the leader’s intimate wishes and “work toward” them are given due place, while the leader’s role in establishing goals and removing limits and rewarding zealous associates plays its indispensable role.

The Tug-of-War between Fascists and Conservatives

Conservatives thought Papen would let them control Hitler. Their experience would let them control the state, while the Nazis kept crowds spellbound. Socialists believed the same thing. The Communist International thought the shift right to Hitler would produce a counter-swing left as democratic illusions were destroyed. Instead, Hitler took on full personal authority. His audacity and drive, his manipulation of the supposed imminent communist terror, let him suspend due process and the rule of law, and even murder his opponents. By July 14th, 1933, Germany was made a one-party state, making open legal struggle impossible.

Conservatives were put on the defensive, trying to maintain their own centers of power against Nazi parallel encroachment. Neither the elderly and sick Hindenburg, nor the relatively timid von Papen could keep Hitler in check. Von Papen denounced Nazi arbitrariness in a speech on June 17, 1934. Hitler had his speechwriter arrested, banned publication of the speech, and closed Papen’s office. Allies of Papen were murdered on the Night of Long Knives two weeks later on June 30, 1934. Von Papen quietly left for a modest post as ambassador to Austria. President Hindenburg died August 2nd, 1934.

Conservatives tried again in early 1938, in reaction to Hitler’s aggressive foreign policy. But this ended too in February 1938, after the officers from the General Staff and the Army Staff were falsely accused of sexual improprieties. Hitler now demanded personal oaths of loyalty from his generals, and remaining officers would not act against Hitler without the support of their commanders. The Foreign Office was also brought under Nazi control by the head of the Nazi parallel organization, Joachim von Ribbentrop. Old SA men started taking on more diplomatic posts abroad.

After the Nazis were defeated in 1945, German conservatives have exaggerated their opposition to the Nazis. In reality, they mainly just defended their personal and class interests.

As we have seen, Nazis and conservatives had authentic differences, marked by very real conservative defeats. At every crucial moment of decision, however - at each ratcheting up of anti-Jewish repression, at each new abridgement of civil liberties and infringement of legal norms, at each new aggressive move in foreign policy, at each further subordination of the economy to the needs of autarky and hasty rearmament - most German conservatives (with some honorable exceptions) swallowed their doubts about the Nazis in favor of their overriding common interests.

Conservatives did hamper one Nazi policy though: the euthanasia of “useless persons,” which will be discussed next chapter.

At the end of the war, as it was clear Hitler was going to lose and destroy Germany in the process, some conservative senior officers and civil servants did resist the Nazis. They even tried to assassinated Hitler on July 20, 1944. Mussolini’s regime is considered less totalitarian, since it did not reach Hitler’s level of control. But the same elements were at play in Fascist Italy as Nazi Germany. Mussolini distrusted his party activists, was forced to share power with the king, and had to placate the Catholic Church. Consequently, some consider Fascist Italy merely a “tougher version of Liberal Italy.”

This is mistaken. It ignores the party’s innovations in organization, propaganda, youth organization, the Ethiopian War, Mussolini’s arbitrariness, and the tensions of the dual state.

The Tug-of-War between Leader and Party

In fascist propaganda, the leader and party are perfectly unified. In reality, they are also in tension. The leader abandons campaign promises, disappointing his radical followers. Mussolini had to face radical squadrismo partisans like Farinacci, and “integral syndicalists” like Edmondo Rossoni. Hitler had better control of his party, but also faced dissent before the Night of Long Knives. Some wanted a “third way” for “German socialism,” which hurt Hitler’s business relations. Others hated Hitler’s “all or nothing” strategy.

When Hitler took power, the party took this as a “second revolution,” and an excuse to use street violence against the Left, moderate bourgeoisie, and Jews. But Hitler needed calm to secure state power, and he announced the “end of the revolution” in summer 1933. The SA still wanted “revolution” though. They wanted to be made the new armed force, which worried the army’s high command. Hitler settled this brutally with the Night of the Long Knives.

Unlike traditional dictatorships, fascists face a constant problem of their party’s energy boiling over and upsetting allies. This requires outlets, with domestic political success, war, occupation, and eventually the murder of Jews.

Mussolini also dominated his party, but faced stronger challenges than Hitler. The local ras had some autonomous power. They conflicted with Mussolini not only as party leader, but also with his push to normalize relations with conservatives. They objected in 1921 to turning the movement into a party. And in August 1921, the ras forced Mussolini to give up his pact of pacification with the socialists.

It was even clearer later on. After Mussolini’s first two years of a moderate coalition, the ras pushed Mussolini to establish one-party rule in 1924. In February 1925, Roberto Farinacci, the violent ras of Cremona, was made secretary of the Fascist Party.

This looked like a renewal of Fascist violence. However, he was dismissed a little over a year later in October 1925, after eight killings in Florence happened “in front of the tourists,” and Farinacci’s law thesis was also shown to have been plagiarized.

More pliable secretaries followed.

The Tug-of-War between Party and State

Hitler and Mussolini had to make the state work for them. The party wanted to replace the old administration entirely, but the leaders never gave in to this demand. Hitler sacrificed the SA to the army in June 1934, with the Night of the Long Knives. Mussolini prevented the Milizia from taking over the Italian army, except in the colonies.

The Fascist and Nazi regimes had no serious difficulty taking over public services. They left professional identities intact, who often liked the fascists’ bias toward authority. Eliminating Jews could even open up career advancement.

The police were also easily incorporated. The German Police were brought under Himmler’s SS. They welcomed this, having felt the Weimar Republic had been “coddling criminals.” The Nazis treated them well too. “Police Day” was extended to “Police Week”. They never faced serious risk of being replaced with SA members.

The Fascists had even less control of the police than the Nazis. They were headed by a civil servant, rather than a Fascist party member. While there was political police with the OVRA, the Fascist police executed relatively few political enemies.

The judiciary was already overwhelmingly conservative, and barely needed to be changed at all. It was already well-established practice to punish communists more harshly than Nazis in the 1920s. In Italy, the judiciary was already extremely political under the liberal monarchy. They were generally sympathetic to Fascism’s commitment to public order and grandeur.

The medical profession is also a notable case. Even if not inherently political, they cooperated with the Nazis especially strongly. The Nazis, unlike the Italian Fascists, were committed to biological purity of the “race.” They were obsessed with birth rates, which overlapped with public health and family concerns.

The cruel experiments of Dr. Josef Mengele can give a distorted picture of Nazi medicine. While it often caused suffering, Nazi medicine was not mere sadism. In fact, they were the first to discover the links between smoking and asbestos to cancer. In the next chapter, we will see this turn towards eugenics, sterilizing the “unfit,” and it's more professional medical approach.

An “astonishing number” of child welfare professionals also cooperated, supporting parental authority and discipline.

The party-state conflict was the most easily and most definitively settled of all the tensions within fascist rule. The Nazi state, in particular, ran vigorously right up to the end, in conscious and determined rejection of any hint of the breakdown of public authority that had occurred in 1918.

Accommodation, Enthusiasm, and Terror

The dual state model is also incomplete because it leaves out public opinion. Was the public terrified into submission by the fascists? Or did they enthusiastically support it? While the terror model is popular, partly because it gives an alibi to people living under the regime, scholarship shows the latter was more common.

It is true that Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy required terror. Nazi violence was high after 1933. The existence of concentration camps was well known. The executions of dissidents were well publicized. But this violence was selective toward “national enemies.” It targeted Jews, Marxists, and outsiders (e.g. homosexuals, “Gypsies,” pacifists, the disabled, criminals, etc.). This gratified Germans more than it terrified them. Only at the end of the war, as the Allies moved in, did violence turn against ordinary Germans seen as disserting.

The Fascist pattern was the reverse of the Nazi pattern. While the Nazis started relatively mild and became more extreme, the Fascists started extreme and became more mild. Their main form of punishment for dissidents was exile to remote villages. A mere nine opponents were killed between 1926 and 1940. But we should not think of Mussolini’s dictatorship as comic. Mussolini ordered the assassination of many people supporting democracy and socialism.

Fascist justice, while several orders of magnitude less vicious than Nazi justice, proclaimed no less boldly the “subordination of individual interests to collective [interests],” and one must not forget the spectacular ruthlessness of Italian colonial conquest.

Like Nazi Germany, Fascist violence was directed at “national enemies.” It targeted socialists, Slavs, and Africans who opposed Italian hegemony. Fascism does not rule by brute force alone. A relatively small police force was able to maintain fascist rule. So many people were reported to the Gestapo, they could get by with less police than the German Democratic Republic, with one officer to every 10,000 - 15,000 citizens.

Fascist contained workers by four means:

Terror

Division

Concessions

Integration

Terror is seen in the socialists and communists sent to concentration camps, even before the Jews. By destroying autonomous worker organizations, fascist regimes were able to address workers individually, rather than collectively. Some concessions were made by both regimes, with official party unions holding a monopoly on labor representation. The Nazi Labor Front had to win some better conditions to maintain credibility. The Third Reich wanted to prevent unemployment or food shortages, which could threaten revolution. Even slavery later in the war worked as a concession of a kind, letting some workers become masters.

Mussolini set up the Labor Charter in 1927, which promised a “corporatist” model that would achieve the common interests of worker and employer.

In practice, however, the cooperative bodies were run by businessmen, while the workers’ sections were set apart and excluded from the factory floor.

Integration was the specialty of fascist regimes. They created youth groups, leisure-time associations, and held party rallies. Peer-pressure, drills, uniforms, and songs make people active participants in the regime.

This was largely successful. Mussolini was popular at least up to his 1936 victory in Ethiopia. Accommodation to the Catholic Church helped tremendously here, ending its conflict with the Italian state. Fascism paid a high price for this alliance, wearing itself out while the Church survived. Mussolini’s military victory in Ethiopia also helped his popularity. However, it declined after Italian expansion started getting defeated, such as against the Spanish Republicans in March 1937.

The Nazis had considerable popular enthusiasm by the mid-1930s. This was helped by full employment and bloodless foreign policy victories.

Fascism was especially popular with the youth. While socialist organizations were destroyed, fascist ones took their place, offering some independence from parents.

Fascism was more fully than any other political movement a declaration of youthful rebellion, though it was far more than that.

Fascism gained substantial support from conservative women by valorizing their roles as homemakers and mothers. However, women were largely able to escape this assigned role, aided by modern consumerism and music. Mussolini did not increase birth rates, and Hitler could not keep women out of the workforce during war.

Intellectuals had a hard time with fascist street gangs that held academia in contempt. Fascists regarded science and art as subordinate to the state.

Since leaders supposedly had supernatural mental powers, fascist militants preferred to settle intellectual matters by a reductio ad ducem.

While some brave liberal and socialist intellectuals spoke against fascism, risking arrest or death, some authentic intellectuals offered enthusiastic support. Mussolini never needed to severely crack down on intellectuals, who were happy to accommodate and pledge loyalty. Intellectual emigration only became significant after racial legislation in 1938.

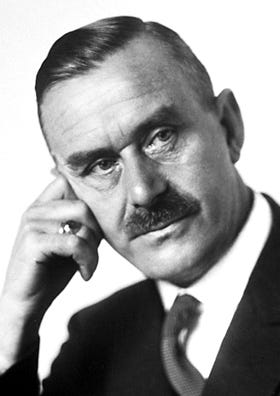

The Nazis were harder on intellectuals, wanting to transform thought away from “Jewish physics” and support “German Christianity.” Substantial numbers emigrated, including non-Jews like Thomas Mann.

Others stayed like physicist Max Plannck, philosopher Martin Heidegger, and legal scholar Carl Schmitt.

The role of other intellectuals as participants or saboteurs remains obscured. Fascism never had complete enthusiasm, but most people accepted it. Some objected, but still accommodated it, having no better alternatives. For example, the orchestra conductor Wilhelm Furtwangler never joined the party, but never dreamed of leaving Germany.

By accepting accommodations of this sort, fascist regimes were able to retain the loyalty of nationalists and conservatives who did not agree with everything the party was doing.

The Fascist “Revolution”

Early fascist rhetoric sounded radical, promising sweeping change. In practice, little changed. Economic and social hierarchies were left intact. Fascist “revolution” differs from the normal understanding of “revolution” we’ve had since 1789 (French Revolution).

Firstly, even early fascists did not attack economic hierarchy, i.e. wealth and capitalism, directly. (See chapter 1)

Secondly, fascist leadership actually reinforced social hierarchy, although it replaced a few “tired bourgeois elites” with fascist “new men.” Fascist change was really seen in the stages of “taking root” and “getting power”. They focused more on alliances rather than assembling the discontent. They broke promises, especially to small peasants and artisans.

Instead of a socioeconomic revolution, fascists want a “revolution of the soul,” and a “revolution” of the relative world power of their people. Fascism was meant to invigorate and empower a decadent nation. They would reassert their dominance by armies, productive capacity, order, and property.

Fascists wanted to revolutionize their national institutions in the sense that they wanted to pervade them with energy, unity, and willpower, but they never dreamed of abolishing property or social hierarchy.

One genuine change in fascism was the nature of citizenship, especially through the subordinated the individual to the community. Fascists did away with liberal individual rights, instead focusing on their “national destiny.” Individual rights could have no autonomous existence, and due process was done away with. Someone released by the court could simply be then picked up and sent to a concentration camp, without legal procedure.

A fascist regime could imprison, despoil, and even kill its inhabitants at will and without limitation. All else pales before the radical transformation in the relation of citizens to public power.

Fascist regimes have no mechanism for people to choose their representative or influence policy. Elections were turned into ceremonies of affirmation, and leaders given unlimited dictatorial power. Fascists blamed community decline on the Left’s preparation for class warfare and proletarian dictatorship. Liberal ideas of harmony were impossible because of the Left, making liberals too weak to stop them. The only solution was to use the state to crush the Left entirely and mold people into disciplined fighters.

Fascism wanted to create “new” men and women, each in their proper sphere. But its challenge was to make someone both a fighter and an obedient subject. Liberal education systems already focused on shaping citizens. Fascists shifted this emphasis to sports, physical training, and military training.

Parallel organizations were also meant to shape upbringing from childhood to university, with obligatory youth movements. Hitler was especially determined here to take away youth away from their parents, teachers, and churches. Once out in the world, people would be further shaped by leisure-time activities like the Dopolavoro (Afterwork Club) in Italy and the Kraft durch Freude (Strength Through Joy) in Germany.

Fascists essentially tried to eliminate the private sphere, which helps radically distinguish it from authoritarian conservatism, and especially from classical liberalism.

There was no room in this vision of obligatory national unity for either free-thinking persons or for independent, autonomous subcommunities. Churches, Freemasonry, class-based unions or syndicates, political parties - all were suspect as subtracting something from the national will. Here were grounds for infinite conflict with conservatives as well as the Left.

Fascists dissolved labor unions and socialist parties. They replaced proletarian solidarity against capital with national identity against other people.

Brooding about cultural degeneracy was a central issue of fascism. Fascists sought to purify the culture from the top of foreign influence. But while fascist propaganda emphasized unity, life remained a complex patchwork of official, spontaneous, and illicit activity. Most art was light entertainment, rather than explicit propaganda. Some Jewish or homosexual artists remained active remarkably late.

In no domain did the proposals of early fascism differ more from what fascist regimes did in practice than in economic policy.

The fascists conceded the most to conservatives on economic policy, especially for the war effort. Fascism is often portrayed as capitalism’s discipline against the workforce. But in practice, businessmen often objected to fascist economic policy, which was more focused on political goals than economic ones. Businessmen preferred fascism to socialism or a dysfunctional market, but it was not their first choice.

Still, they would learn to acquiesce and work well within these regimes. Mussolini’s corporatism being run by businessmen is a striking example. As Peter Hayes put it, the Nazi regime and business had “converging but not identical interests.”

The agreed on:

Disciplining workers

Lucrative armaments contracts

Job creation stimuli

They conflicted on:

Government economic controls

Limits on trade

High cost of autarky, requiring substitutes of previously imported products like oil or rubber

But businessmen got more from the Nazi regime than the Nazi radicals did. It was not the radical Otto Wagener that became minister of the economy, but Kurt Schmitt, head of Germany’s biggest insurance company.

While Nazi radicalism did not disappear, the economic radicals generally resigned, lost influence, or were murdered. In the short term, fascist economies could look more capable than the floundering liberal economies in the Great Depression. But they never achieved the growth of post-war Europe, or even pre-WWI Europe.

This makes it difficult to understand fascism as a “developmental dictatorship” for latecomer industrial nations.

Fascists did not wish to develop the economy but to prepare for war, even though they needed accelerated arms production for that.

Fascists cut back on the welfare state, but neither fascist regime tried to dismantle it. Fascism was revolutionary in its radically new conception of citizenship and civilian life. But it was counter-revolutionary in terms of traditional projects of the Left like individual liberty, human rights, due process, and international peace.

In sum, the fascist exercise of power involved a coalition composed of the same elements in Mussolini’s Italy as in Nazi Germany. It was the relative weight among leader, party, and traditional institutions that distinguished one case from the other. In Italy, the traditional state wound up with supremacy over the party, largely because Mussolini feared his own militant followers, the local rasand their squadristi. In Nazi Germany, the party came to dominate the state and civil society, especially after war began.

Fascist regimes functioned like an epoxy: an amalgam of two very different agents, fascist dynamism and conservative order, bonded by shared enmity toward liberalism and the Left, and a shared willingness to stop at nothing to destroy their common enemies.