A Summary of Proudhon's "What is Property" - Ch. 2

Property Considered as a Natural Right. Occupation and Civil Law as Efficient Bases of Property. Definitions.

Intro: Thoughts on Chapter 2

My notes on chapter 1 can be read here. What is Property can be read here.

In this chapter, Proudhon lays out some very important distinctions between the idea of “property” and “possession,” especially focusing on a legal definition that would be familiar to French law from the time. Once this definition of property is clearly in mind, he actually considers three different arguments given in favor of property: (1) property as a natural right, (2) property as acquired through occupation, and (3) property as established by civil law.

The first section where Proudhon defines his terms is especially useful, and crucial for understanding his argument. On the one hand, there is this idea of property, where someone has a right to control that thing. Crucially, this includes a right to control it even as others use it, even turning it into a source of profit for the proprietor. The possessor, by contrast, is the person who actually uses and occupies the thing. When Proudhon denounces property as theft, he seems to be relying precisely on this kind of distinction. This is not a distinction he is inventing either, but one already found in the legal system.

The clearest example of this is probably the case of a landlord and a tenant. The landlord is a proprietor. They own the land, but do not live on it. The tenant by contrast is the possessor. They live on the land, but do not own it. Through this division, the landlord, as the absolute ruler over their domain, is able to establish rules that the tenant must follow, and may also charge them rent simply for continuing to exist in that space.

Proudhon clearly wants to argue in favor of possession against property. How he imagines this is, ironically, pretty well illustrated by an example offered in favor of property: the theater.

The theater, we are told, is common to all. Everyone can go in and pick their seat, and through that they gain a kind of limited right to it. It would be wrong to take someone’s “spot” in the middle of a show. But once the show is over and people return the next day, you can pick whatever seat you like.

This is clearly a claim based on occupancy. Your right over that seat is based on the fact that you are using it. We might tweak this system some depending upon the norms of that society and the way “normal” use looks (e.g. it might be “saved” if you have to leave temporarily to get more popcorn), but at the end of the day it is still something based on possession.

With this in mind, Proudhon’s other arguments are also quite interesting. Against the claim that property is a natural right, he is quick to point out that no one treats it this way. If property really were this absolute, inalienable natural right, then it seems like the law is violating this right constantly. Through things like the progressive tax system and welfare, the government constantly needs to transfer wealth from the rich to the poor.

Now, propertarians today might cheer when they read these lines, being perfectly willing to agree with this and proclaim their desire for “anarcho”-capitalism. Proudhon does not appear to have expected anyone to be quite so ridiculous. The point of his example was that all of these violations of property are necessary because it is a fundamentally anti-social right. Property has set the rich and poor at war with one another. Society cannot survive without violating property.

Even if we were willing to bit that bullet though, he has another point: If property really were a natural right, then why do we spend so much time debating its origin? Why focus so much on how we acquire property, if it is naturally ours? We don’t do that for any other natural right. If it really were a natural right, we should expect it to be equal in everyone, entitling each to their own portion of the total social wealth. In other words, it would push us right back to equality and possession.

This brings us to the arguments around occupancy. I have already covered the basics of the theater point, which really seems to be the running theme. We see people constantly trying to justify property in terms of mythical/historical narratives about a “state of nature” or “primitive communism,” with property developing out of that. But each argument seems to rely on the need to possess something, and fails when it tries to make it an argument about property.

If occupancy is the basis of property, then the amount of property we are entitled to changes with the number of occupants.

Having torn these arguments down (which I have to admit sometimes only seem loosely related to occupancy, like the guy who argues about “thine and mine”), Proudhon considers people who seem less interested in the philosophical principles justifying property and instead just want to say we need it as a matter of practical necessity.

Proudhon’s case here is interesting, because he shows not only how the arguments used to justify property only seem to justify possession, but also gives his own interesting historical narrative about how property itself might have been established to better secure equality. Property seems like a “first draft” attempt at an egalitarian system, which can now be replaced by something better since we can identify its errors. If the argument in favor of property was based on this practical necessity then, Proudhon has shown how we keep needing to destroy property for practical reasons. He had already doing this from the beginning, in fact, as we saw in his argument around property as a “natural right.”

A few other comments stand out as well. Proudhon actually draws an interesting comparison to marriage as a form of property, in contrast to a lover being mere possession. On it's own, this seems like an implicit critique of marriage and it's treatment of women. Given Proudhon’s own misogyny and patriarchal views on marriage, it is surprising to see this included as his own go-to comparison.

Summary of Chapter II: Property Considered as a Natural Right. Occupation and Civil Law as Efficient Bases of Property. Definitions.

Legal Definitions

We begin our critique of property with a series of definitions to give us a better understanding of what exactly we are talking about.

Roman law defines property like this:

The right to use and abuse one's own within the limits of the law.

It is interesting that property is described as “abuse” here. Some have tried to excuse or justify this by claiming that this does not refer to immoral and senseless abuse, but only indicates the proprietor’s “absolute domain” over their property.

A useless distinction and a worthless excuse! This “absolute domain” includes the right to destroy and waste, i.e. to engage in immoral and senseless abuse. Use and abuse are indistinguishable when it comes to property.

The French definitions for property built off the Roman one. The Declaration of Rights from the Constitution of 1793 defines property like this:

The right to enjoy and dispose at will of one's goods, one's income, and the fruit of one's labor and industry.

The Napoleonic Code defines things similarly:

Property is the right to enjoy and dispose of things in the most absolute manner, provided we do not overstep the limits prescribed by the laws and regulations.

In both cases we see this “absolute domain” concept borrowed from Roman law.

The caveat found in all of these definitions that things must be “within the limits of the law” hardly changes anything either. It is not a limit upon property, but rather a demand that the property of others be respected where that domain ends.

There are also two different senses about property which is extremely important for us to distinguish:

Domain - This is “naked” property pure and simple, representing the “dominant and seingorial power over a thing.” This is especially see as a matter of right.

Possession - This is a matter of fact, often contrasted directly against the right of property.

To illustrate this, a possessor would be a tenant or the usufructuary (i.e. the person with the right to use and benefit from property while ownership belongs to another). A proprietor would be who lends at interest or an heir set to come into possession of something upon the death of the current user.

To give a comparison, a lover is a possession while a husband is a proprietor.

It is vital that we understand this double meaning of property (domain vs possession) to understand the critique of property that is to follow.

(NOTE: While Proudhon here lists possession as a form of property, his critique actually seems to be against property as domain while defending possession and contrasting it to property. As domain is “naked property,” fitting most closely to the definitions he saw before, he appears to have this in mind whenever he refers to property without qualification, and not possession.)

This distinction between possession and property leads to two sorts of rights:

Jus in re - Right in a thing

Jus ad rem - Right to a thing

Jus in re is based on possession, allowing us to reclaim what we have acquired no matter whose hands we find it in. It unites property and possession together. For example, the right a married couple has over the other’s person.

Jus ad rem is based on property, allowing us to become a proprietor. It is only naked property, separate from possession. For example, the right of a betrothed couple over the other’s person.

As a laborer, Proudhon claims a right to possess the products of Nature and his own industry. Yet as a proletarian, he enjoys neither. Presenting his critique of property as a legal case, he is claiming by virtue of this jus ad rem that he is demanding jus in re, returning possession to the proletariat.

This distinction between jus in re and jus ad rem is also the basis for two types of legal actions:

Action Possessoire [Possessory Action] - Related to possession

Action Petitoire [Petitory Action] - Related to property

On behalf of the entire proletariat, Proudhon intends for this book to be a universal action petitoire, establishing that those who lack possession today are proprietors by the same title as those who do possess. But instead of concluding that property should be shared by all then, he demands that property be abolished entirely.

Legally, a plaintiff who cannot make an action petitoire is barred from bringing an action possessoire. If the proletariat succeeds in its own action petitoire, it may move on, if necessary, to an action possessoire, reestablishing their possession over what has been denied to them by property.

1. Property as a Natural Right

Some claim that property is a natural right.

The Declaration of Rights claims there are four such natural rights:

Equality

Liberty

Security

Property

Charles Toullier in his Droit Civil Expliqué (Civil Law Explained) names three rights:

Security

Liberty

Property

We can see that Toullier eliminated equality from his list. Did he do this because it is implied by liberty, or because it is incompatible with property?

Regardless, property is out of place in either of these lists. For most people, it is a “natural right” which exists for them only in potentiality. Even for those who do have property, it is not respected as a natural right. Everyone views property as a chimerical illusion.

Natural rights are meant to be absolute and inviolable. We can see this pretty clearly in the other examples listed of liberty, equality, and security.

Our liberty is absolute. It cannot be sold away or alienated. “The slave, when he plants his foot upon the soil of liberty, at that moment becomes a free man.” Only when someone declares themselves a public enemy, attacking the liberty of others, may they be seized and deprived of their liberty themself.

Equality before the law is similar. Every citizen is equally eligible to hold office, with family holding no influence. In the name of justice, the poorest citizen may demand their rights against someone in the most exalted office.

The same is true for security. Society promises us complete defense, not merely defense when it is convenient. Society promises either to avenge us, or perish along with us. Its entire strength is available for every citizen.

Property is not like this at all. It is not treated as absolute or inviolable at all in practice, nor could it be. Worshiped by all, it is acknowledge by none, and everyone plots its death and ruin.

The first example of this is the progressive tax system, which charges the wealthy a higher rate of taxes than the poor. Now, the existence of taxes itself seems justified, as all should contribute to the expenses of government which performs its task for all. But why charge the rich more than the poor if property is this inviolable natural right?

The purpose of government is supposed to be to defend our natural rights, to maintain order, and to provide useful and pleasant public services. But it doesn’t seem more costly to do any of these things for the rich than the poor. On the contrary, it's often cheaper since they can provide for more of their own needs with their additional wealth. Why then are they being taxed more? If property really were a natural right, a higher tax could only be just if there were some greater proportional service they received.

Some try to get around this problem by treating the government as a “justice corporation,” which sets up the police and courts to defend the right of property against the “mob” of the poor. But such a “mob” only exists because of property! It created this division between the rich and the poor, setting them at war with one another.

Other natural rights don’t work this way. Affirming the liberty, equality, and security of any individual reaffirms it in everyone else, uniting them together. They mutually strengthen and sustain one another. But property forces the haves to defend themselves against the have-nots.

The second example is the the existence of a welfare system for the poor, such as the English poor-rates. If property really were an inalienable natural right, how could we possibly justify taking taxing some just to give to the poor? When we tell the rich to give to the poor, this is meant to be an act of charity, not law!

The third example is seen in the popular French demand for the conversion of the 5% bonds, lowering the rate of interest on public debt. This would clearly violate the “natural” right of property of the bondholders. While the state has a right to do this if the public need is great enough, there should be just compensation to the property holders. But providing this compensation would defeat the entire point of lowering the rate of interest!

The state is meant to provide absolute security. If property is a natural right, how then can it infringe upon it this way? We are stuck with conflicting claims then, as one group defending property denounces taking away this source of income for a few families, while the taxpayers denounce raising taxes on a million more families to pay them.

In summary, we can clearly see that liberty, equality, and security are all absolute rights. Liberty is necessary to our existence, equality is necessary for society, and security guarantees that our lives our equally valued. Each gives as much as they receive.

But property is a right outside of society. If all wealth were social wealth, then clearly it should be equal for each. Property therefore, if it is a natural right, is an anti-social right. It is incompatible with liberty, equality, and security. Property and society are irreconcilable. One must go. We must either destroy society or destroy property.

It is clear that, as much as these governments might claim property is a natural right, it is not treated this way in practice, nor could it ever function that way. It is wholly unlike other natural rights, and unworkable as a consistent system, requiring these violations of a supposed “natural” right.

There is another oddity: If property really is a natural right, they why do so many people debate about its origin? Natural rights are inherent to us and born with us. But once again, property is so different! The law says it exists for people who aren’t even born yet, and remains after we die.

The defenders of property all agree that its validity depends on its origin, but they do not agree on what that origin is meant to be. How strange then that they affirm it so strongly as a right then! Usually their responses break down to two possible origins: occupation and labor. Both arguments, as we shall see, ultimately fail. Even if we take their arguments for granted, which we will do now for, we will see that they all imply equality.

2. Occupation as the Title of Property

The Napoleonic Code

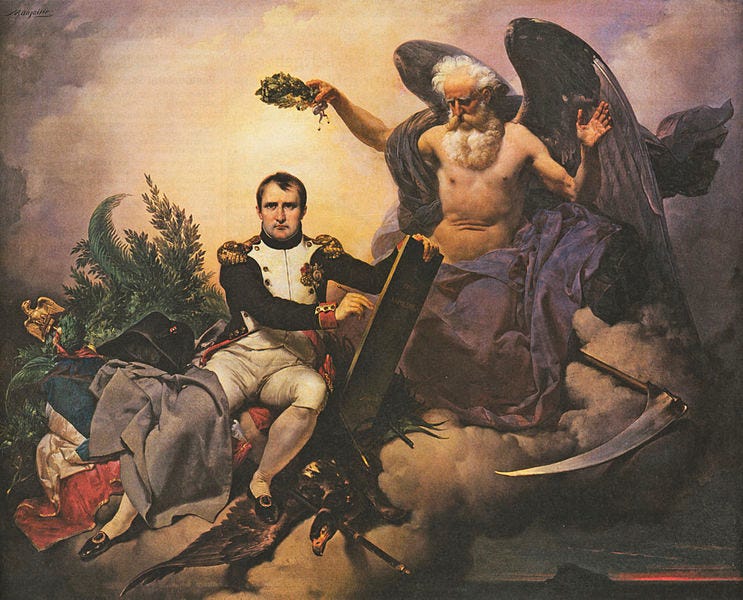

The Napoleonic Code has surprisingly little to say about the origin of property, apparently just assuming it is uncontroversially based on occupancy. This seems to fit with Napoleon’s own attitude.

Bonaparte, who on other questions had given his legists so much trouble, had nothing to say about property. Be not surprised at it: in the eyes of that man, the most selfish and willful person that ever lived, property was the first of rights, just as submission to authority was the most holy of duties.

Cicero

We instead turn then to Roman law, which seems to propose the idea of the right of occupation, or rather the right of the “first occupant.” By actually possessing a thing, such as by occupying a piece of land, I am taken to be its proprietor unless proven otherwise. To be legitimate, this right must also be reciprocal with others.

We see this expressed by Cicero:

[Quemadmodum] theatrum cum commune sit, recte tamen dici potest eius esse eum locum quem quisque occuparit…

Just as, though the theatre is a public place, it is correct to say that the particular seat a man has taken belongs to him…

This analogy is the only passage in all ancient philosophy on the origin of property. But if taken seriously, it clearly destroys property. The theater is made common to all, but each seat someone takes is something possessed by them. Unless we are dealing with the monster Geryon from Greek mythology, who had three bodies, it is impossible for someone to simultaneously occupy three seats spread across the theater.

By this logic, no one has a right to more than they need. This gives us the axiom “suum quidque cujusque sit” or “to each that which belongs to him,” i.e. what they have a right to possess. This right of possession matches our need. It is what is required for our labor and consumption, as illustrated by the theater example. The analogy leads directly to equality. The theater is owned by all. Each space occupied is merely tolerated, and it is a mutual (i.e. equal) toleration between all.

Grotius

The Dutch jurist Hugo Grotius (1583-1645), whose writings laid the foundation of international law and modern theories of rights, gives a historical origin for this so-called “natural” right. According to him, mankind began in a state of primitive communism, where all was the property of all. However, through a system of wars, and then through a system of treaties and agreements, this communism was ended and replaced with a system of property.

But what was the nature of these treaties? Either they were based on equality, the only system these primitive communists were familiar with, or they were unequal, the strong imposing their will upon the weak, making them null and void as contracts. Property was meant to be justified by its origin, and this is a clearly unjust origin which is not remedied by the tacit consent of later generations. We live in a permanent condition of fraud. If we began in equality, then we must return to it.

Reid

The Scottish philosopher Thomas Reid (1710-1796) agreed that property was not an innate right, but an acquired one. He agreed more or less in line with Cicero’s analogy, arguing the Earth is commonly owned by all. To appropriate one part for ourselves then, this must be done in such a way that no one else is harmed by that appropriation. He even uses Cicero’s analogy of the theater, saying each person may appropriate an empty seat and thereby gain a right to it so long as the show lasts, but may not dispossess others of their seats.

Three things immediately follow from this theory:

Each person is entitled to an equal share of the total.

No one can occupy multiple places.

When enter or leave, the share each person is entitled to adjusts accordingly.

This final point especially follows from the fact that Reid admits property is only an acquired right, not an absolute one. Their claim on that property was conditioned on occupancy and it harming no one, and it cannot have a greater stability than that condition.

Reid seems to have even realized this himself, admitting that our right to life must imply a right to the means of life. If we take this seriously, it follows that all people must therefore have an equal right to the means of production. Reid lacked not in knowledge to pursue this conclusion. He only lacked courage.

We can clearly see how depriving someone of the means of life is akin to murder in this example:

Would it not be criminal, were some islanders to repulse, in the name of property, the unfortunate victims of a shipwreck struggling to reach the shore? The very idea of such cruelty sickens the imagination.

The proprietor, like Robinson Crusoe on his island, wards off with pike and musket the proletaire washed overboard by the wave of civilization, and seeking to gain a foothold upon the rocks of property.

“Give me work!” cries he with all his might to the proprietor: “don’t drive me away, I will work for you at any price.”

“I do not need your services,” replies the proprietor, showing the end of his pike or the barrel of his gun.

“Lower my rent at least.”

“I need my income to live upon.”

“How can I pay you, when I can get no work?”

“That is your business.”

Then the unfortunate proletaire abandons himself to the waves; or, if he attempts to land upon the shore of property, the proprietor takes aim, and kills him.

Tracy

Next we can consider the arguments of Destutt de Tracy (1754-1836), the French philosopher who coined the word “ideology,” who gives a more materialist explanation of property.

According to him, property is a consequence of human nature. He admits that property causes much suffering, but that is a category impossible for us to abolish. Specifically, it is meant to come from the mental categories “thine and mine.” Because we necessarily think in this way, property also necessarily follows from human nature.

This is a very silly and weak argument though, since we can talk about “thine and mine” in ways that do not imply property at all. We can speak of your country, my tailor, your church, my uncle, etc. “Thine and mine” merely indicate a relation, and that relation can easily be applied to a mere system of possession rather than of property. We can talk about “my seat in the theater.”

Tracy’s whole argument rests on this simple equivocation, although he tries to cover over this by painting a much bigger story. Whether it is a true or false story is irrelevant. Following Hobbes (and rejecting Rousseau), he describes a state of nature where people are estranged from each other, living in a state of extreme inequality and barbarism. To escape this miserable state, agreements were made with one another, establishing the concepts of “justice” and “injustice.”

We can put it this way: in the state of nature, rights were only equal in the sense that all were free to injure anyone else. It was an “equal right” to do evil, and therefore of course allowing the strongest to dominate, therefore creating the most extreme inequality of conditions. If the agreements people made were to escape this situation, it was precisely to move towards equality of conditions, bringing a balance between the weak and the strong. By this very story, society only exists through equality. When they were not equal, they lived as strangers and enemies, and therefore had no society between them.

This is where Tracy sees property come in. Thanks to these agreements, we have developed a sense of justice, and along with that a sense of certain rights and duties. And then, because have rights and duties, we have them as property. As he put it:

But to have needs and means, rights and duties, is to have, to possess, something. They are so many kinds of property, using the word in its most general sense: they are things which belong to us.

We’re just back to the whole “thine and mine” thing! The word property has a double meaning (besides the one we gave before of domain and possession): (1) property as qualities, and (2) property as a right of absolute control over something by a person. These senses must not be conflated. To say “iron takes on the properties of a magnet” is very different from saying “I take this magnet as my property.” Similarly, to tell someone because they have properties that they therefore have property is to make a false equivocation. As Proudhon responds:

To tell a poor man that he HAS property because he HAS arms and legs, — that the hunger from which he suffers, and his power to sleep in the open air are his property, — is to play upon words, and to add insult to injury.

This point seems so obvious that it is almost a joke, but that is exactly the argument Tracy makes. He argues that when we become aware that we have certain things (e.g. a body, capacities, actions, organs, etc.), we must also see ourselves as the proprietor of these things. Not only is this argument silly, but is also relies on this same conflation between properties and possessions.

In summary, Tracy conflates external products of nature (land, forest, water) and our internal faculties (e.g. memory, strength, imagination, etc.) as “property.” To put it another way, there are some forms of property which are acquired, and others which are innate. Through this conflation, he hopes to turn property into a firm right which may never be disturbed. He constructed this whole story about the state of nature, but even this story goes directly against his case. In the state of nature, the strongest (with the best internal faculties) appropriated the best external products for themselves. If society was established to fix this, it was to fix this relation between the weak and the strong, correcting the inequality of innate properties through the equality of acquired property. This is therefore not a story of how property came to be, but how society destroys property.

Dutens

Joseph Dutens (1765-1848) is an engineer with no background in philosophy. Despite this, he wrote a book called “The Philosophy of Political Economy.” In it, he defines property like this: “Property is the right by which a thing is one’s own.” A worthless answer that reduces to “property is the right of property.”

From here, he basically follows Tracy’s reasoning with different language and concludes with two principles:

Property is a natural and inalienable right of every man.

Inequality of property is a necessary result of Nature.

We could reduce this to one: All men have an equal right to unequal property.

The rest of his argument is similarly a mess. For example, he critiques Sismondi for saying property is only a right by convention, but then goes on to argue that property is established by the “original contract” of society, i.e. establishing by convention. Overall he is a seriously confused thinker who constantly mixes up terms, not really worth analyzing further.

Cousin

The French eclectic philosopher Victor Cousin (1792-1867) has a more interesting approach, grounding property and all morality and law in one command:

Free being, remain free!

Bravo! Sounds great! Let's see where this gets him.

Cousin argues like this: If the human person is sacred, then so is our liberty. This sacred liberty needs an instrument to act, which is our body. Thus we need individual liberty. This instrument also needs material to work on. This is the basis of property, as it not “participates” with the inviolability of our person. Our free activity, our free labor, is therefore a basic condition of property. But there is another condition: to not infringe upon the labor of others, I must be the first occupant. If I pass these tests, then I have the right to property. I may also donate this property to whoever I want, including determining who to bequeath it too. This decision is as valid after death as it is during life.

Proudhon argues there is one more condition Cousin should add: Time. Suppose the first occupants have occupied everything. What are newcomers meant to do? What happens to these “sacred human people” if they are denied any material to work on?

It is also worth noting that Cousin thinks neither labor nor first occupancy alone can justify property, but only a combination of the two. This seems to be one of his famous “eclectic” approaches. Instead of using systematic analysis, he jumbles together whatever ideas sound good to him. But the point of this section is to take these people’s arguments for granted and show that they ultimately imply equality, so we can look past that for now.

If liberty is equally sacred in all, and this liberty requires property, then there is also an equal right of appropriation. In a world of infinite resources, we could appropriate as much as we want. But in a finite world, it follows that the amount we may take is limited is proportional to the number of people. This would remain the case as people are born and die, with the proportion we may take shrinking and growing proportionally. Any newcomer set to become an heir would have no right of accumulation by their inheritance, but only a right of choice.

This can be said even more simply: People need to work to live. To work, we must be able to access tools and material. This need constitutes our right, giving all a claim on what is available, proportional to the population. Therefore, our society should share the means of labor equally with all, and leave each individual free.

Cousin has gone the farthest in his defense of property, but as we’ve seen it is still not enough.

But maybe some are still not convinced. Some people are wary to follow principles and definitions to their extreme, and will be happy to contradict them when they consider it expedient and practical to do so. Even if they find the origins of property questionable then, they might still think it is simply good jurisprudence to keep it.

Against this, let’s consider these arguments and show how the law itself constantly undermines property by trying to base it on equality.

3. Civil Law as the Foundation and Sanction of Property

Pothier

The French jurist Robert Joseph Pothier (1699-1772) traces the origin of property back to God. God is the absolute ruler of the universe and has granted control of the Earth to humanity, placing all things beneath our feet and commanding us to be fruitful and multiply.

But if the Earth has been given to humanity, why has it not been divided equally? How can we be fruitful when we have been left homeless?

We get a different answer then. Originally, we are told, men lived in communism without property or even private possession. But as possession was created and grew, more labor was needed for its support, therefore requiring some kind of agreement. The law was established, granting title to the laborer to the fruit of their labor. It followed that whoever took, by force or fraud, someone else’s means of subsistence has destroyed equality and stands outside the law.

But it also follows that whoever monopolized the means of production itself broke equality and became unjust too. Labor therefore gives a right to possession: jus in re. But in what thing? In the product, not the soil! This is exactly how the Arabs have practiced things. If you planted crops, you could reap the wheat you have sown, but you wouldn’t own the land because of that.

The only thing this story about civil law has explained is how we moved into a system of possession. It has not told us how we moved from possession into property. What argument can we give to claim property against society? I possess as occupant, as laborer, and by social contract. But none of these establish the anti-social right of property. Against my claim, society can claim it is the original occupant of the world. My labor was only a condition of possession. The social contract established with me only gave a right of use.

Why would society ever recognize a law injurious to itself? That would fly entirely in the face of establishing property on civil law rather than on philosophical principles!

Ancillon

The German statesman Friedrich Ancillon (1767-1837) tried to give his own answer to this problem. He argued that it was useless to try to distinguish our ownership of an “improvement” against ownership of the object improved (e.g. owning the crops, but not the farm land) because form cannot be separated from the object. But if that’s true, and possession cannot be distinguished from property, then possession should be shared by all.

Furthermore, if property is just a creation of civil law, then society may also place the conditions on property ownership too. It could charge the property owner for their ownership, taking away all excess beyond what they need to live and work the land. This payment would not be rent, but an indemnity.

Consider what this argument means for the law.

We are told that, because form and substance cannot be separated, either society or the laborer must be disinherited. Society owned the substance, while the laborer owns the improvements. But then, unlike every other case where property in the substance gives property in the improvements (minus their cost), we are suddenly told that in this case the improvements should extend ownership back into the raw material!

Ancillon thinks the law should side with the individual against society, when it’s clear the logic of his argument should imply the reverse.

This is the exact type of nonsense reasoning our legislators use. The law is meant to be for protecting our mutual rights. When we have set up a system of law that pits man against society, our law is at fault.

Toullier

The strangeness of this situation is admitted by Charles Toullier (the same guy who eliminated equality from the list of natural rights in section 1). He agrees that it’s not clear how we moved from possession to property, but argues the move, however it was done, was justified to accommodate population growth. Through property, he claims, we are able to secure that the person who sows will also be able to reap. But that is clearly wrong. Possession does that, no property. In fact, property works against it, giving the proprietor a right of escheat over land they do not work.

Toullier continues that, because of this supposed need for property, the civil State was created to institute and uphold the law. Property is therefore the cause of government, which then turned property into something permanent.

This argument concedes that property is artificial. It is not the expression of some innate psychological fact or moral principle, but just something that happened to fit the needs of circumstance. Property created the state, which then made property permanent. Thus we made an establishment out of greed.

Yet even here we are pursuing equality. This need property was supposedly a solution to was to secure the weak against the strong, making sure they could continue to access the means of production and keep the fruit of their labor. Someone needs land to work each year, so each citizen was granted their own permanent spot.

Doing this also helped fix other problems. For example, people cannot occupy the same plot all the time. If men needed to be sent off to fight in a war, they needed land they could come back to. Thus it became customary to maintain property through intent alone.

Likewise, to maintain the original equality this property was meant to establish over generations, it also became customary to maintain that division through inheritance, going either to the first born as a matter of simplicity or to be divided among all the children.

Even if the intent was equality though, this policy was clearly short-sighted. This is a forgivable mistake we might expect from a more primitive man who had no access to statistics or political economy.

Today we have the opportunity to approach the problem scientifically. The founders of law lacked foresight, and did not see that their system built on equality could lead to inequality. By the right of transfer, maintenance by intent, and system of inheritance, inequality becomes more and more entrenched. Inheritance especially shows this as we see how property becomes increasingly unevenly divided depending on the number of children several generations down the line on different sides of the same family.

We can now see through the lies of common arguments for property.

What is justice without equality of fortunes? A balance with false weights.

In summary, occupation not only leads to equality, but prevents property. All have a right of occupation, to have material to labor on. What each is entitled to varies with the size of the population then. Possession cannot be fixed as property. Each occupant is a possessor, not an owner. It is entrusted to them, not absolutely, but in a way in conformity with general utility. There is no right to abuse.

We must establish a new code to reflect this fact along these lines:

All have an equal right of occupancy.

The amount occupied being measured, not by the will, but by the variable conditions of space and number, property cannot exist.

But the proprietor keeps looking for more excuses, so they turn to their next option: Labor. But this argument is even worse, as we will see in the next chapter.