Introduction

While writing Read On Authority, my in-depth critique of Engels’ essay “On Authority,” I had originally intended to include a section detailing the history of Engels’ relation to anarchism. This would have given greater context for how and why the essay was written, showing early versions of his argument included in various letters, and how Engels came to his many misconceptions about anarchists or allowed his personal biases to influence him. Since “On Authority” had original been published in Italy, I meant to especially focus on his relation with the anarchists there.

However, it soon became clear that doing this story justice would have required too much background information that would have been irrelevant to “On Authority” itself. For a paper that was already quite long, this section took up more and more space, or became more time-consuming as I double-checked information. Furthermore, since this history mostly involved me presenting or summarizing the research of others, I wanted to avoid any unintentional plagiarism. As I wanted to release my paper in December on the 150th anniversary of “On Authority’s” publication, time was running short.

This paper is the end result of that research, focused primarily on Engels’ relation with the International Workingmen’s Association (which I will also refer to as simply the IWA, the International, or the First International) in Italy. “On Authority” was written in the immediate aftermath of the IWA’s Hague Congress of 1872, which is when the International officially split apart. However, I will only be covering the period leading up to this Congress as the Congress itself was complex enough that it would likely need to be covered by a separate paper.

I want to especially give credit to the fantastic and extremely detailed case provided by Wolfgang Eckhardt’s The First Socialist Schism, as well as Robert Graham’s We Do Not Fear Anarchy, We Invoke It and Nunzio Pernicone’s Italian Anarchism, 1864-1892, all of which are wonderful histories of this period of time. I will try to provide heavy footnotes for where I am pulling my information from. Eckhardt especially remains one of my main sources of information, and much of what I write here could be seen merely as an adaptation or summary of their masterful research, as my extensive quoting and citations should demonstrate.

Background of the International and the Alliance

The conflict between Engels and the International in Italy needs to be understood in the broader context of the conflict between Karl Marx and Michael Bakunin. Italy was ultimately only one battlefield within this broader conflict.

The International was founded in 1864. As the name implies, it was an international organization made up of various worker associations that shared the common aim of the emancipation of the working classes, putting into practice the slogan “Workers of the world, unite!” This “big tent” structure allowed it to represent various different socialist tendencies and ideologies, advocating different ways of achieving this shared end goal.

The IWA allowed these groups to establish communication with each other, allowing the workers to learn from the experience of others on the effectiveness of their methods and otherwise plan collective action. As the IWA’s General Rules put it:

1. This Association is established to afford a central medium of communication and co-operation between workingmen's societies existing in different countries and aiming at the same end; viz., the protection, advancement, and complete emancipation of the working classes.

To facilitate this goal, the rules also established several other ways the IWA would be organized, including holding a General Congress every year made up of delegates chosen by the workers of each nation. This Congress would pass resolution and declare common aims of the IWA to keep the association functioning, and adapting it to changing circumstances, allowing major decisions of the association to be controlled by the workers themselves.

This Congress would also appoint a General Council which would function for the rest of the year, acting as a central bureau to keep workers informed about what was going on in other countries and what challenges were being faced. This would allow workers to act in a simultaneous and uniform manner. This Council could also bringing proposals as needed, and would facilitate communication with regular reports. Again, this is defined within the rules like this:

6. The General Council shall form an international agency between the different and local groups of the Association, so that the workingmen in one country be consistently informed of the movements of their class in every other country; that an inquiry into the social state of the different countries of Europe be made simultaneously, and under a common direction; that the questions of general interest mooted in one society be ventilated by all; and that when immediate practical steps should be needed — as, for instance, in case of international quarrels — the action of the associated societies be simultaneous and uniform. Whenever it seems opportune, the General Council shall take the initiative of proposals to be laid before the different national or local societies. To facilitate the communications, the General Council shall publish periodical reports.

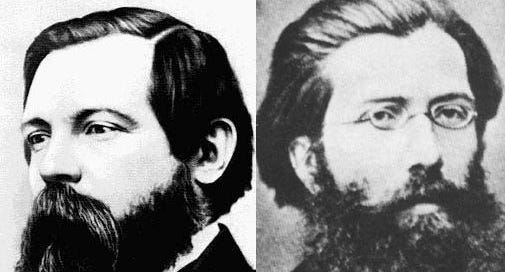

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels were members of this General Council, and much of their influence on the socialist movement can be credited to their positions there, helping to establish a “Marxist” movement.

Likewise, revolutionary anarchism also began within the International, especially thanks to the work of the Russian exile Mikhail Bakunin and the organization he helped establish, the Alliance of Socialist Democracy, which became one of the many organizations that made up the International.

Marx had an odd relationship with Bakunin from the start.

On July 6, 1848, years before the International was established, Marx had publicly accused Bakunin in his paper, The New Rheinische Zeitung, of being a secret agent of Tsar Nicholas I. This accusation was supposedly based on a report from the French novelist George Sand.

Seeing his name being slandered, Bakunin wrote to Sand, who denied that she had made any such claim. She wrote to Marx clarifying that she had no such evidence, forcing Marx to make a retraction.1 He published her letter in his paper, adding a comment that, by publishing these rumored accusations before verifying things with Sand herself, he had “only accomplished the duty of the public press, which has severely to watch public characters. And, at the same time, we gave to Mr. Bakunin an opportunity of silencing suspicions thrown upon him in certain Paris circles.”2

Marx and Bakunin did not interact much over the following years until shortly after the IWA was founded. Marx met Bakunin in person and seemed to have gotten along with him quite well. Marx wrote to Engels in November 1864:

Bakunin sends his regards. He left today for Italy where he is living (Florence). I saw him yesterday for the first time in 16 years. I must say I liked him very much, more so than previously. … On the whole, he is one of the few people whom after 16 years I find to have moved forwards and not backwards.3

Marx’s views on Bakunin here are rather shocking, considering where their relationship ends up. At this point, Marx considered Bakunin to be a key ally in the region. In April 1865, Marx wrote to Engels about using Bakunin in Italy as an opponent to the Italian republican nationalist Giuseppe Mazzini, saying “I shall get Bakunin to lay some counter-mines for Mr Mazzini in Florence.” This positive impression seemed to last through 1867.4

Bakunin joined the International in June or July 1868 after it began gaining prominence.5 For a short while after he remained active in the bourgeois anti-war League of Peace and Freedom, trying to push it into a more radical direction, but his collectivist idea failed to win most of them over. When the IWA Congress in September 1868 appealed for League members to leave it for the International, Bakunin agreed. He left the League entirely, and brought several other members with him.6

While these members all intended to join the International (although Bakunin was already a member), they also wanted to maintain their close working relation with one another. They pledged to continue working towards their revolutionary goals in a secret unofficial capacity, while also establishing a legal public-facing organization. This became the International Alliance of Socialist Democracy, which stated directly within their founding program that they were to be a branch of the International.7

Marx was upset by this and began to once again view Bakunin as a conspirator intent on bringing the IWA under “Russian leadership.”8 The Alliance was rejected from the International primarily on two grounds. The first was that the Alliance was established as an international organization, and was therefore actually considered a competitor to the IWA itself. Admittance into the IWA would require them to disband.

Secondly, their founding program declared that they wanted the “political, economic, and social equalization of classes and individuals of both sexes.” Marx argued that the “equalization of classes” could be read as the call for “harmony of capital and labor,” which contradicted the International’s goal of class abolition. Marx recognized this appeared to be a “slip of the pen” though, and Bakunin’s own writings confirm that he viewed equalizing classes as the same as abolishing the class distinctions between them.9

The Alliance modified their program accordingly. They broke up as an international organization, and their new program called for “the final and total abolition of classes and the political, economic and social equalization of individuals of either sex”.10 Having complied with these requests, Marx himself moved for the General Council to admit them on July 27, 1869, despite his remaining and growing suspicions against Bakunin.11

The Alliance faced further difficulties after joining, becoming especially isolated by the more conservative elements of the IWA due to its openly atheistic, collectivist, and revolutionary nature. The Alliance’s radicalism was seen as detrimental to various electoral campaigns these reformers wanted to promte. In Geneva, the Alliance was excluded from the Romande Federation. While their rules did not allow them to exclude official members of the IWA, the Alliance’s application was “indefinitely postponed.”12

A major fear among these groups was that the Alliance was going to “impose” atheism on the rest of the International. This became especially intent among people who believed Bakunin planned on taking over the International. In reality, the Alliance had no such plans, and only aimed to persuade people to adopt their positions rather than impose this view from the center. In fact, the Alliance believed it would be a great detriment to the IWA, as an organization aimed at bringing all the workers of the world together, if it were to only admit atheist workers. The International was to remain a pluralist organization. As Bakunin described it,

We think that the founders of the International were very wise to eliminate all political and religious questions from its program. To be sure, they lacked neither political views nor well defined anti-religious views. But they refrained from expressing those views in their program because their main purpose, before all else, was to unite the working masses of the civilized world in a common movement. Inevitably they had to seek a common basis, a set of elementary principles on which all workers should agree, regardless of their political and religious delusions, simply so that they might show themselves to be earnest workers, that is, harshly exploited and long-suffering.

Had they unfurled the flag of some political or anti-religious system, they hardly would have united the workers of Europe but instead would have divided them even more; for the priests, the governments, and even the reddest bourgeois political parties, aided by the workers' ignorance, have disseminated a horde of false ideas among the working masses through their own self-interested and highly corrupting propaganda.13

While facing this opposition in Geneva, Bakunin and the Alliance found more allies in the Jura mountain region of Switzerland. The conservative opposition to the Alliance largely came from Genevan fabrique, luxury clockmakers and goldsmiths serving an elite clientele, but the watchmakers of the Jura region served an international market and had already learned that there was little hope for change through their elected representatives, instead utilizing industrial action in the formation of labor unions.14

Engels and the International in Italy

The first section of the International in Italy was founded in Naples in January, 1869. It quickly grew to 3,000 members within a year before being destroyed by police suppression.

Thanks to his earlier activism in Italy and dispute with Mazzini, Bakunin had a fairly sizeable influence in the country, whereas Marx, Engels, and the General Council had essentially no contacts whatsoever. Engels wrote to Marx on February 11, 1870 that “Spain and Italy will have to be left to them [Bakunin and his fellows], of course, at least for the time being.”15

This would begin to change when Marx and Engels connected with a young Carlo Cafiero while he was traveling through Europe. Engels assigned him the task reorganizing the recently destroyed Italian International to the liking of the General Council. However, the Council was not popular in the area, so Cafiero was met with a rather cold reception. Further, by the time he actually returned to Italy in the middle of 1871, the International had already effectively rebuilt itself, having regained several hundred members.16

To prepare him for Italy, Engels sent a letter in early July 1871 explaining the ideological differences between himself and Bakunin:

Bakunin has a theory peculiar to himself, which is really a mixture of communism and Proudhonism; the fact that he wants to unite these two theories in one shows that he understands absolutely nothing about political economy. Among other phrases he has borrowed from Proudhon is the one about anarchy being the final state of society; he is nevertheless opposed to all political action by the working classes, on the grounds that it would be a recognition of the political state of things; also all political acts are in his opinion 'authoritarian'. Just how he hopes that the present political oppression and the tyranny of capital will be broken, and how he intends to carry out his favourite idea on the abolition of inheritance without 'acts of authority', he does not explain.17

Marx and Engels misunderstood Bakunin’s position on abstentionism and opposition to inheritance, as I covered briefly within Read On Authority.18 They believed that, by talking about abstention, Bakunin wanted workers to do nothing at all about the government, effectively wishing it away. In reality, did call for workers to take action, but wanted this to be direct action by the workers, carried out their their own organizations independent from the state or capital. The call for abstention from politics was therefore really a call for abstaining from bourgeois politics, such as refusing to run candidates in state elections, to preserve this independence from the institutions they ultimately planned on overthrowing.19

Despite this criticism, Engels surprisingly continues on in his letter to defend Bakunin’s place in the International, emphasizing its pluralist structure and warning against forming ‘sects,’ a favorite term of Marx and Engels. Agreeing with the reasoning we saw from Bakunin earlier, Engels argues that this pluralism is a great strength of the International as an association of all the workers of the world:

Now our Association has been founded to provide a central means of communication and joint activity for the working men's societies existing in different countries and aiming at the same end, viz., the protection, advancement and complete emancipation of the working classes (1st Rule of the Association). Since the particular theories of Bakunin and his friends come under this rule, there can be no objection to accepting them as members and allowing them to do what they can to propagate their ideas by every appropriate means. We have people of all sorts in our Association—communists, Proudhonists, unionists, commercial unionists, cooperators, Bakuninists, etc.—and even in our General Council we have men of widely differing opinions.

The moment the Association were to become a sect it would be finished. Our power lies in the liberality with which the first rule is interpreted, namely that all men who are admitted aim for the complete emancipation of the working classes.20

However, Engels lamented that Bakunin seemed to reject this pluralistic structure, instead wanting to impose upon everyone the program of the Alliance. If Cafiero was to be an effective agent of the General Council, he would need to be vigilant against these subversive “Bakuninists,” a label not actually used by the anarchists themselves.21

Unfortunately the Bakuninists, with the narrowness of mentality common to all sects, were not satisfied with this. In their view the General Council consisted of reactionaries, the programme of the Association was too vague. Atheism and materialism (which Bakunin himself learnt from us Germans) had to become compulsory, the abolition of inheritance and the state, etc., had to be part of our programme.22

Engels is clearly playing into that same conservative fear that existed in Geneva against the Alliance. He is framing himself and the General Council as the great defenders of pluralism, reflected within even the Council itself, while the “Bakuninists” were a “sect” that wanted to tear this down.

As we saw before, Bakunin did not intend on imposing atheism on the International. Nor did he intend on imposing any other part of his program, and for very similar reasoning. Bakunin denied that any universal system for the workers could be discovered, and therefore encouraged the pluralism of the IWA, not as a bug, but as a feature. As Bakunin put it:

To hope to establish a perfect theoretical solidarity among all the sections of the International today would be to subscribe to a singular illusion. Indeed, has this solidarity ever existed in the world? […] However, an ever greater and more complete unification of theoretical ideas shall not fail to occur in the future under the double influence of progressive science, on the one hand, and the gradual unification of interests and social positions on the other. But this can only be the work of centuries, and if we wished to found the emancipation of the proletariat on the basis of this perfect theoretical solidarity, it would be long in arriving.

It is the eternal honour of the first founders of the International and, we willingly admit, of comrade Karl Marx in particular, to have understood this, and to have sought and found, not in any economic or philosophical system, but in the universal consciousness of today’s proletariat, certain practical ideas resulting from their own historical traditions and everyday experience, which one shall find in the feelings or instincts if not always in the conscious thought of the workers of all countries in the civilised world, which constitute the true catechism of the modern proletariat.23

The notion of “perfect theoretical solidarity” was dismissed as impossible in modern society, and likely could only ever be achieved long after workers have gained their emancipation. A pluralistic approach to the revolution was therefore necessary.

Cafiero, in his own interactions with the “Bakuninists” of Italy, similarly came to the conclusion that they did not want to impose their program on anyone. He wrote back to Engels:

I can assure you that he [Bakunin] has several friends here in Naples who share many of his principles and have a similar point of view as him, but to go so far as to say that he has a sect, a party that clashes with the principles of the Gen[eral] Coun[cil], that I can justifiably deny.

[…] No member of the International with whom I have spoken in Italy expects those principles of atheism, materialism, the abolition of hereditary rights, common property, and so on, to be written into articles of our society’s pact; on the contrary, they would oppose this with all their strength; but on the other hand they are quite tenacious in wanting to lead all the members of their branch into sharing those ideas.24

Cafiero, by actually speaking to the “Bakuninists” (or more accurately the friends of Bakunin), came to a much more accurate grasp of their position in contrast to Engels’ imagination. Rather than looking to impose a program upon the workers as Engels imagined, they instead saw themselves as an especially revolutionary force that, through persuasion and example, could inspire workers to join them in a more radical direction. While they of course believed that their own ideas were the best to spread, they did not intend to set themselves up as an authoritarian “sect” over the International.

Engels responded with glee, interpreting the absence of any Bakuninist sect as a sign that Bakunin had little influence whatsoever. In his reply to Cafiero on July 28, 1871, he used his previous misplaced warning as greater evidence of “Bakuninist” treachery:

We are pleased to hear that there is no sign of the Bakuninist sect over there. We had been led to believe the reverse because the Swiss Bakuninists always asserted it to be the case. They repeated it constantly and since we received no reply from Naples to our letters we believed it.25

Engels doubled down on the sectarian nature of the “Bakuninists,” recounting to Cafiero how they had originally been established as an international organization. That they were admitted as individual sections after that point was taken as a sign of the IWA’s great commitment to pluralism and dedication to upholding the first of their general rules. However, Engels then goes on to clarify that this first article of the General Rules only applied to admission, and that the General Council did not need to maintain this kind of pluralism in its own theoretical announcements.

I have given you these extensive quotations in order to prove the unfoundedness of any accusation that the General Council would be overstepping the limits of Article 1 of the Rules. In its official powers regarding the admission or refusal of divisions, it certainly cannot act in this way. But as regards discussions of theoretical points, the Council desires nothing more ardently than this. From discussions of this sort the Council hopes to arrive at a general theoretical programme acceptable to the European proletariat. […] Read all the addresses that have been sent to you, and in particular number 5, the one on the civil war in France, where we declare ourselves in favour of communism, a fact which will no doubt have displeased the many Proudhonists in the Assembly. […] No document has been issued by the General Council which does not go beyond Article 1.26

In Engels’ view, the pluralism of the International was seen more as a bug than a feature, and it was the task of the General Council to resolve this by developing a “general theoretical programme” rather than giving a representative presentation of the views of their membership.

Engels’ strange view of pluralism gets even odder after that. While before he defended the pluralistic view the Council takes towards admissions, and condemning the Alliance’s supposed plan to impose atheism, Engels admits this to Cafiero:

As for the religious question, we cannot speak about it officially, except when the priests provoke us, but you will detect the spirit of atheism in all our publications. Moreover, we do not admit any society which has the slightest hint of religious allusion in its statutes. Many wanted to apply, but they were all invariably rejected.27

This was the state of things in Italy as of July 1871. It is interesting that Engels would warn against the dangers of sectarianism and attempts at imposing programs, warning that it would lead to the destruction of the International, given the following events.

The London Conference and the Sonvilier Circular

In a General Council meeting on July 25, 1871, Engels proposed for that year’s General Congress be suspending, and instead proposed holding a “private conference” in London, which was where the Council operated from, on the third Sunday in September.28 The Congress has similarly been suspended in the previous year of 1870 due to concerns regarding the Franco-Prussian War. Paul Robin had called for a similar conference to make up for the the 1870 Congress on March 14th, 1871, but this had been entirely opposed by Marx and Engels. Now the same measure was being adopted by Engels, but only so that that year’s Congress could be called off as well.29

Technically, there was no provision in the rules to allow for a conference of this sort, as Engels himself admitted, describing the London Conference as “a compromise and was not provided for in the rules.”30 Later he even described it as “an illegal mechanism, justified only by the gravity of the situation.”31

Because this was a private conference “not provided for in the rules,” the General Council did not need to follow any rules of procedure that would apply to a normal Congress, such as the requirement to disclose to the sections of the IWA when it would take place or what it would be about. The sections of the IWA, if they were told about the Conference at all, were largely kept in the dark about what its actual content would be, or could even be actively mislead. Both Marx and Engels insisted that the conference would deal only with organizational issues rather than theoretical ones, and a list of nine non-theoretical resolutions were proposed by the General Council. In the actual Conference, there were ten additional resolutions which dealt heavily with very important theoretical questions. The sections in the International were not involved in drawing up the agenda, nor were they informed about it beforehand.32

The Conference did not only deviate from the normal procedure of a Congress in laying out its agenda. In Marx’s view, the General Council was to be considered a “governing body, as distinct from its constituents.”33 In line with this view, the Council voted to give itself delegates at the conference with the right to speak and to vote, despite the fact that they represented no section or nation within the International. They debated among themselves the exact number of delegates to give themselves, with Engels actually suggesting they should have an unlimited number of voting delegates.34 The Council voted to give itself voting delegates, and at the very eve of the Conference set the number of voting delegates to six.35

On top of this, since some nations were not able to send delegates to the conference (some were not even informed it was taking place), Engels moved to make the Council’s secretaries for each non-represented nation the delegate in their place.36 Since they were just appointing themselves to this position, there was no actual mandate given from the nations they were representing on how they must vote, effectively giving the Council six more votes.

This would be:

Italy - Friedrich Engels

Germany - Karl Marx

Ireland - Joseph Patrick McDonnell

United States - Johann Eccarius

England - John Hales

France - Eugène Dupont37

Engels, a German who lived in England, had only been made secretary to Italy a little over a month prior on August 1, 1871. On this basis made himself the entire country’s representative to vote on what he intended to be binding resolutions.38

On top of this, nine more members of the General Council attended the Conference. In total the London Conference was therefore made up of 21 members of the General Council, 12 of which were delegates with the power to vote.39

By contrast, a mere 9 delegates were actually sent by the sections of the International. This would include:

Belgium - Six delegates with mandates

Spain - One delegate with a mandate, Anselmo Lorenzo Asperilla

Switzerland - Two anti-Bakuninists, including Nikolai Utin40

Various resolutions in the Conference were aimed at undermining or denouncing Bakunin and the Alliance. Previously, in the Romande Federation’s La Chaux-de-Fonds Congress in April 1870, the Alliance had successfully forced the issue of their “indefinitely postponed” application and were admitted into the Federation in a vote of 21 to 18. The minority of anti-Bakuninists, including Utin, went into an uproar, and the two sides of the Federation were forced to continue things on entirely separately, each claiming to be the true continuation of the Federation.41

At the Conference, Marx proposed an impartial five-person commission be created to settle the dispute between the two factions. Utin nominated Marx as a member of this “impartial” commission, which he accepted despite some objections. Engels also took the role of taking minutes for this commission, despite not being part of it, and Utin remained to denounce Bakunin without opposition. The actual reason for the conflict, the vote of the La Chaux-de-Fonds Congress, never came up. The commission sided with the anti-Bakuninsts, and with Resolution No. 17 the Conference “decreed” that the Jura sections should form a new organization called the “Jura Federation.”42

This and several other resolutions were directly aimed at Bakunin and the anarchists, but the most contentious was Resolution No. 9, which dealt with the demand that the workers form political parties with the aim of the conquest of political power. According to Eckhardt, the various positions in the Conference can be broken into three categories:

The conquest of political power through parliament (represented by Marx, Engels, and others).

Labor struggles and the rejection of participation in parliamentarianism (represented by André Bastelica).

The conquest of political power while rejecting parliamentarianism and labor struggles (represented by the Blanquist Édouard Vaillant, who initially suggested the resolution).43

This clearly marked not only a mere organizational issue of the International, but a massive ideological divide between separate factions and a matter of deep theoretical interpretation, a matter Marx and Engels had assured people this Conference would not deal with at all. Despite objections from the Spanish delegate Lorenzo that such questions should be left to a more representative Congress, Utin and Marx dismissed his concerns.44

Notably, to support this resolution, Marx continually referred back to the Inaugural Address of the IWA, a document he had written but had never been put to a vote by any Congress, as a binding document upon the entire International. Engels likewise had elsewhere described it as “official and essential commentary on the [General] Rules.”45

Proposals to move this question to the next Congress failed, but there was lively debate around the exact wording the resolution. The Council-dominated Conference tasked the General Council to finish the exact wording, granting them to revise the resolution even after the London Conference. Two weeks later the General Council created and adopted a revised version of the resolution. Then, after it had been adopted, Marx changed the wording of this resolution again.46

The final version of the resolution can be seen here:

Considering, that against this collective power of the propertied classes the working class cannot act, as a class, except by constituting itself into a political party, distinct from, and opposed to, all old parties formed by the propertied classes;

That this constitution of the working class into a political party is indispensable in order to ensure the triumph of the social revolution and its ultimate end — the abolition of classes;

That the combination of forces which the working class has already effected by its economical struggles ought at the same time to serve as a lever for its struggles against the political power of landlords and capitalists —

The Conference recalls to the members of the International:

That in the militant state of the working class, its economical movement and its political action are indissolubly united.

Engels, who just a few months ago warned Cafiero of the evils of the “Bakuninist” sect who wished to impose political abstentionism on the membership, had now helped to impose an anti-abstentionist orthodoxy upon the International.

The London Conference was soon after opposed by the Jura Federation. On November 12, 1871, they published a rebuke called the Sonvilier Circular, which I covered partially in Read On Authority.

Against Marx’s view that the General Council needed to exist as a “governing body,” the Circular argued that it was a “central bureau of correspondence”:

When the International Worker's Association was created, a General Council was set up whose function, according to the statutes, was that of serving as Central Bureau of correspondence between the Sections, but which was not delegated any authority whatsoever, which would have been contrary to the very essence of the International, which is only an immense protest against authority.

This argument followed with an extensive citing of the general statutes and regulations of the IWA to make their case, as well as a history of how more power had been given to the Council, such through administrative resolutions at the Basel Congress of 1869 (which ironically, Bakunin and the Jura Federation had a hand in, much to their later regret),47 including the power and right to suspend sections of the IWA and settle disputes between branches until the next Congress. This turned out to have given over far more power than expected, not only because it was used much more aggressively than anticipated, but because Congresses were simply no longer being held at all. This power, the Circular argued, had a corrupting effect:

If there is one incontrovertible fact, borne out a thousand times by experience, it is that authority has a corrupting effect on those in whose hands it is placed. It is absolutely impossible for a man with power over his neighbours to remain a moral man.

This rise in power of the Council was responsible for their increasing view of themselves, not as a bureau of correspondence, but as a government who could enforce its own theoretical views, and sees all opposing tendencies as sects.

Having, in their own eyes, become a sort of government, it was natural that their own particular ideas should have come to appear to them as the official theory enjoying exclusive rights within the Association; whereas divergent ideas issuing from other groups struck them, not as the legitimate manifestation of an opinion every bit as tenable as their own, but rather out-and-out heresy.

The Circular recounted the ways in which the Council had gone beyond even this by replacing the General Congress with its own private conference, giving itself as many delegates as it pleased, and exercising authority against sections it disliked.

Since the Basel Congress in 1869, the General Congress of the Association has not been convened, and the General Council found itself left on its own during the last two years. The Franco-German war has been the reason for the absence of a Congress in 1870 and 1871. The Congress has been replaced by a secret Conference summoned by the General Council even if the Statues did not give it this power. This secret Conference, that certainly didn't grant a full representation of the International, as many Sections, ours included, were not informed; this Conference whose majority was manipulated from the start because the General Council had taken the licence of admitting six delegates elected by it with the right to vote; this Conference which absolutely could not pretend to be invested of the rights entitled to a Congress, has nevertheless taken some resolutions which gravely infringe the General Statutes and intends to transform the International, from a free Federation of autonomous Sections, to an hierarchical and authoritarian organization composed of disciplined Sections placed under the power of a General Council which can, at its own mercy, deny their admission or even suspend their activity. And, to crown all this, a decision taken at this Conference, establishes that the General Council will fix the date and the place of the next Congress or of the Conference which will replace it. In this way we are threatened with the suppression of the General Congresses, these large public conventions of the International, and their substitution with secret Conferences similar to the one just held in London.

This central issue of the principle of authority being introduced into their association was seen as the root cause of the issue. The Jura Federation denied the Council of having any “criminal intent,” but that this is rather the inevitable outcome of the power they had been given and their ideals of “the conquest of political power by the working class,” pushing to make the International more hierarchical.

The Circular therefore demanded that autonomy be restored to the sections of the International, that the Council be reverted to its original role, and that the International finds its unity, not in centralization and dictatorship, but “upon a free federation of autonomous groups.” This is because the Jura Federation endorsed the central anarchist idea of the unity of means and ends, believing that the way we structure our organizations now should reflect the kind of future ideal we wish to achieve, whereas hierarchical structures would only grow more opposed to emancipation. They therefore conclude with a call immediately for a new General Congress:

The society of the future should be nothing other than the universalisation of the organization with which the International will have endowed itself. We must, therefore, be careful to ensure that this organization comes as close as possible to our ideal. How can we expect an egalitarian and free society to emerge from an authoritarian organization? Impossible. The International, as the embryo of the human society of the future, is required in the here and now to faithfully mirror our principles of freedom and federation and shun any principle leaning towards authority and dictatorship.

Our conclusion is that a General Congress of the Association must be summoned without delay.

Long live the International Working Men’s Association!

Thus the Jura Federation led the movement for a mass protest within the International against the General Council.

It is worth noting that Bakunin had no hand in this Circular, but was nevertheless quickly blamed for it by Marx.48

The End of the General Council’s Influence in Italy

Meanwhile Naples remained the center of the International in Italy, but they had fallen below 300 members by June 1871. On August 14th, 1871, increasingly concerned about the existence of the International, the Italian minister of the interior ordered for the section to be dissolved and its leaders indicted for political subversion. No trial was ever held though, and only Cafiero spent any time in jail and had to pay a heavy fine. This political repression won them sympathy from the general public, as Cafiero wrote to Engels:

Ah! Yes, my dear friend, the government has done us much good with its persecution. My arrest was a real treasure … it broke the ice, and for more than 15 days all the newspapers of Italy spoke of nothing else but the International, incendiarism, the crazy communists, the callow youths who disavow the beliefs of their parents, etc … In sum, for better or worse, the International in Italy is a fact, publically and frankly affirmed; it has entered to become part of the normal life of the people.49

Despite this repression, the Neapolitan International continued to operate underground, officially reconstituting itself in December 1871.

The resolutions of the London Conference became known in Italy in November, and immediately caused serious issues. On November 13, 1871, the Italian Carmello Palladino wrote to Engels:

I have read some of the decisions taken at the last Conference; and I must tell you frankly that I simply do not accept them; both for the way that the Conference itself was convened, which was certainly not in compliance with our General Rules; and for the paucity of delegates, who arrogated the rights of a general congress; and finally for the very tenor of those decisions, which in my opinion openly contradict the principles of our Association as established by our General Rules.50

Cafiero, as the Council’s representative who needed to explain and defend their actions, similarly wrote to Engels on November 17, 1871 about the uproar resolution 9 was causing, begging for more information:

There has been a little agitation here because of that blessed Conference, which I shall not repeat as Palladino already speaks of it in his letter. That resolution no. 9 has been understood as a concession on the 3rd recital of our Rules. The idea of a political party, even one opposed to all the other bourgeois parties, caused scandal and there were cries of treason about bourgeois elements having joined the International and made their way as far as the Conference. I love to see how our founding pact is watched over so that it not be violated but rather scrupulously fulfilled. But I always like to keep quarrels and splits at bay. Please give us more information about this matter, though I believe that by this stage other complaints of the same nature will have reached you.51

Engels kept Cafiero on his side by deceiving him about the nature of Resolution 9, saying it did not require the formation of a workers’ party at all, leading Cafiero to publicly defend it as actually supporting “Bakuninist” abstentionism in December.52

Engels, who we saw recognized the Conference as an “illegal mechanism,” responded back to Palladino on November 23:

I am sorry you think yourself duty-bound to tell me that you in no way accept the resolutions of the last Conference. Since it is evident from your letter that an organised section of the International no longer exists in Naples, I can only assume that the above declaration expresses your individual opinion and not that of the Naples Section, now forcibly dissolved.53

The dig about the section being “forcibly dissolved” from the General Council’s official secretary to Italy is a reference to this heightened police repression.54

Engels continued to respond to Palladino’s objection point-by-point, but lied in his answers. He claimed that the sections had assented to the conference (they had not), and that no objections to its legality had been made beforehand (they had, and even Engels agreed it was an “illegal” compromise).55

With regard to Palladino’s complaint about the small number of delegates, that this was outside of the Council’s control, but that

Belgium, Spain, Holland, England, Germany, Switzerland, and Russia were direct represented. As to France, it was represented by practically all the members of the Paris Commune then in London, and I hardly suppose you would dispute the validity of their mandate.56

The truth is that, of this list of seven countries, only three were represented: Belgium, Spain, and Switzerland. Holland and Russia were not represented at all. England and Germany were represented by members of the General Council (so not directly represented), as was Ireland, the United States, France, and Italy. Engels conveniently leaves out that he had personally represented Italy. No such French mandate existed because the only communards in attendance were all delegates of the General Council. Engels also reasserted the line that the resolutions passed were of a “purely administrative nature,” when resolution 9 especially marked a radical departure on an extremely important theoretical question.57

Engels, the secretary to Italy for the General Council, the organization established to keep the workers “consistently informed” about what was going on in other countries, was trying to cover for the nature of the Conference by lying to the Italians about it.

Cafiero was not merely reporting on the criticisms other workers had against the London Conference, but even criticized it himself. He wrote to Engels on November 28:

Let me return again to the Conference, to tell you that this resolution no. 9 is creating embarrassment of all sorts for us, as it confuses a position that had been quite distinctly defined in the General Rules. […] In other words, if that resolution remains, either my hands will be tied as far as my propaganda work, etc. is concerned and I shall be unable in any way to do what I do, or I shall have to stand unequivocally alongside those who reject it […].58

It is important to also note that the Sonvilier Circular would only reach Italy in late November and early December. Cafiero’s reports and concerns represent the direct and authentic reaction of the Italian workers to the London Conference itself.59

Facing intense backlash, on November 30th, Engels made the following declaration:

Citizen Giuseppe Boriani is accepted member of the International Working Men's Association and is authorised to admit new members and form new sections, on condition that he, and the members and sections newly admitted, recognise as obligatory the official documents of the Association, namely:

The General Rules and Administrative Regulations,

The Inaugural Address,

Resolutions of the Congresses,

The resolutions of the London Conference of September 1871.

By order and in the name of the General Council Secretary for Italy,

Frederick Engels60

Recognition of the legality of the “illegal mechanism” of the London Conference was now an official requirement for membership within the International in Italy, as was the authority of Marx’s Inaugural Address.61

The General Council was flagging badly in Italy, and needed some win to show the Italian people that they still meant business.

Luckily, around the same time, the republican nationalist Mazzini was still waging his campaign against the Paris Commune and the IWA, publishing a series of articles called “Documents about the International.” Here was Engels’ chance, as secretary to Italy, to show the value of the General Council, working as the best informed center of communication to combat the errors and slanders spread about them.

Engels commented on this in a letter written to Paul Lafargue on December 9, 1871, stating “I have been working hard at Italy and we have now begun to shift the battleground; from private intrigue and correspondence we are moving into the public arena. Mazzini has given us an excellent opportunity…”.62

What was this excellent opportunity? Would Engels establish himself as the great defender of the International? Well, in Mazzini’s attack, Bakunin had been mentioned in a footnote, quoting a speech he had delivered to the League of Peace and Freedom. The opportunity Engels saw was to “attack Mazzini and disavow Bakunin at one and the same time.”

Engels had written the following letter on December 6, 1871:

TO THE EDITORS OF LA ROMA DEL POPOLO

In number 38 of La Roma del Popolo Citizen Giuseppe Mazzini publishes the first of a series of articles entitled "Documents about the International". Mazzini notifies the public:

"I ... have gathered from all the sources I was able to refer to all its resolutions, all the spoken and written declarations of its influential members."

And these are the documents he intends publishing. He begins by giving two samples.

I. "The abstention" (from political action) "went so far that some of the French founders [of the International] promised Louis Napoleon that they would renounce all political action provided he grant the workers I don't know what sum of material aid."

We defy Citizen Mazzini to prove this assertion which we regard as calumnious.

II. "In a speech at the Berne Congress of the League of Peace and Freedom in 1868, Bakunin said: 'I want the equalisation of individuals and classes: without this an idea of justice is impossible and peace will not be established. The worker must no longer be deceived with lengthy speeches. He must be told what he ought to want, if he doesn't know himself. I'm a collectivist not a communist, and if I demand the abolition of inheritance rights, I do so to arrive at social equality more quickly'."

Whether Citizen Bakunin pronounced these words or not is quite immaterial for us. What is important for the General Council of the International Working Men's Association to establish is:

that these words, as Mazzini himself asserts, were spoken at a congress not of the International but of the bourgeois League of Peace and Freedom;

that the International congress, which met at Brussels in September 1868, disavowed this same congress of the League of Peace and Freedom by a special vote;

that when Citizen Bakunin pronounced these words, he was not even a member of the International;

that the General Council has always opposed the repeated attempts to substitute for the broad programme of the International Working Men's Association (which has made membership open to Bakunin's followers) Bakunin's narrow and sectarian programme, the adoption of which would automatically entail the exclusion of the vast majority of members of the International;

that the International can therefore in no way accept responsibility for the acts and declarations of Citizen Bakunin.

As for the other documents about the International, which Citizen Mazzini intends to publish shortly, the General Council hereby declares that it is only responsible for its official documents.

By order and in the name of the General Council of the International Working Men's Association,

Secretary for Italy,

Frederick Engels63

This is the letter Engels was so proud of, showing he had been “working hard” in Italy.

Technically, Engels is wrong here. In point 3 he claims Bakunin was not a member of the IWA in September 1868. In fact, he had joined a few months earlier in June or July, as I covered above.

More importantly, all this letter essentially amounts to is a “prove it” for the first claim, and the second claim is a factually inaccurate response which denounced Bakunin’s “narrow and sectarian programme,” while it was in fact Engels and the London Conference who had just imposed their own program which was now excluding “the vast majority of members of the International” in Italy as Engels had just days ago decreed that recognizing its legitimacy was a requirement for membership. Engels doesn’t even bother to explain to the Italians how Bakunin’s program is meant to be sectarian, intending it to be just taken for granted! More than anything else, Engels failed in Italy because he simply didn’t want to deal with people where they were or engage with Bakunin as representing a serious ideological split. Engels was too focused on the “real movement” to deal with real people.64

Before the issue of the London Conference, the Italian workers largely did not know about Marx and Engels’ conflict with Bakunin. Rather, Bakunin was the member of the International most publicly combating Mazzini (Bakunin published in this same month his book The Political Theology of Mazzini and the International, which was far more successful as a rebuke), something he was originally doing with Marx’s blessing. The conflict between Geneva and London was largely unknown, as Engels had spoken to few others besides Cafiero about it.

Now, seemingly out of nowhere, they had not only been drawn into this conflict, and in an open letter to Mazzini of all places, the General Council was attacking their own greatest anti-Mazzini champion. His response to Mazzini involved no actual substantive rebuke against Mazzini himself, except to the extent he (accurately) associated Bakunin with the International.

Cafiero was once again left to pick up the pieces of Engels blunders. He affirmed Bakunin’s many friends here and the positive general impression he had in the Italian International even among people who did not know him. He wrote back:

With regard to your declaration in reply to Mazzini, I must confess that if it had depended on me, I would have done everything possible to avoid its publication. I feel it is my duty to set out my opinion of this document clearly to you. I believe that declaration to be an eminently misguided act, […] I believe that it was a mistake to pick an argument over a note [about Bakunin] lost at the foot of an article in the Roma del Popolo in order to fire the first shot of a battle whose outcome could not be calculated. With that document you have broken the eggs in my hand, as they say in Italy. With the help of the last clarifications on res 9, I was in quite a strong position and I was all set to write to you saying that I was delighted that you had given me the means with which I could ward off a terrible crisis in Italy, warmly entreating you not to insist on publication of the reply to Mazzini. And now I receive the Gazzettino Rosa with the fatal document there, black on white […].65

Cafiero’s comment on “clarifications” on resolution 9 is referring to Engels’ previously noted deception, where it did not require the formation of a party and actually was more in line with abstentionism.

To make matters worse for Engels, Cafiero began to profess his commitment to “anarchism” as part of materialist rationalism. Engels’ greatest ally in Italy was slipping through his fingers.

Meanwhile, protests continued to grow against the General Council. The Belgian federal congress was held around Christmas of 1871 and passed a number of resolutions with strikingly similar language to the Circular, even going further in calling for a revision of the rules themselves to prevent the kind of authoritarian organizing on display at the London Conference.66

Engels in Denial

Engels wasn’t finding any new allies in Italy. Despite his proclamation that new members must recognize the London Conference, the Circular was making its way through Italy and was attracting widespread support.

In October 1871 a new Workers Federation formed in Turin, but which sided with Mazzini against the International. Carlo Terzaghi sent a letter to the General Council to inform them about it, forming a separate organization with about 270 members, and asking for financial support for their paper. Engels agreed at first, but when Bakunin began spreading the Circular in late December, Terzaghi’s section decided they would send a delegate to the new Congress the Jura Federation called for. Engels rescinded his offer of money along with an angry letter on January 6, 1872, decrying Terzaghi for not waiting for the Council’s response, which incidentally would not have been published until four and a half months later as Fictitious Splits in the International.67

However, Engels did publish his own response on January 10, 1872 called “The Congress of Sonvilier and the International,” blaming the Jura Federation under Bakunin’s leadership for having thrown an “apple of discord” into the International. Engels found the Circular’s view of the General Council, in contrast to their view that it should exist as a governing body, and its advocacy for a “free federation of autonomous sections” to be bizarre.

To our German readers, who know only too well the value of an organisation that is able to defend itself, all this will seem very strange. And this is quite natural, for Mr. Bakunin's theories, which appear here in their full splendour, have not yet penetrated into Germany. A workers' association which has inscribed upon its banner the motto of struggle for the emancipation of the working class is to be headed, not by an executive committee, but merely by a statistical and correspondence bureau!68

In Engels’ conception, the emancipation of the working classes could not be achieved “by the working classes themselves” unless they were properly directed by an executive committee.

Engels flatly rejected the unity of means and ends. The proletariat’s fight for emancipation must be authoritarian in form. He continues:

We Germans have earned a bad name for our mysticism, but we have never gone the length of such mysticism. The International is to be the prototype of a future society in which there will be no executions à la Versailles, no courts-martial, no standing armies, no inspection of private correspondence, and no Brunswick criminal court! Just now, when we have to defend ourselves with all the means at our disposal, the proletariat is told to organise not in accordance with requirements of the struggle it is daily and hourly compelled to wage, but according to the vague notions of a future society entertained by some dreamers.

It is crucial that we understand Engels’ interpretation of the unity between means and ends if we are going to understand the rest of his argument.

For the anarchists, this unity of means and ends represents the idea that, to achieve our aim of the emancipation of the working classes, our methods of practice and organizational forms, in other words the systems we produce and reproduce, will determine the sort of society we achieve. Thus, while the exact actions and purpose an organization serves may shift and develop over time due to changing circumstances, there would be no dramatic break in our form of organizing now and how we organize in a future society. For example, in his Ideas on Social Organization, the anarchist James Guillaume argued that labor unions which today unite the workers in defense of their wages and against the attacks of the employers, will continue to unite workers in socialism, but now for the purposes of production and education about their industries. This is a theory of social change rooted in a theory of practice, literally in the sense of how practicing something develops our drives and capacities to better implement and achieve it. To achieve the emancipation of the working classes, we must organize in a manner that rejects domination. The anarchist strategy is to achieve this through a system built upon free association and federation.69

For Engels, this idea of a unity of means and ends was instead a rejection of the recognition that we do not live in a future society, therefore demanding complete non-action in the present, which is how he understood the call for “abstention.” Because of this, he described a nightmarish scenario where the ideas of the Jura Federation were put into practice:

Let us try to imagine what our own German organisation would look like according to this pattern. Instead of fighting the government and the bourgeoisie, it would meditate on whether each paragraph of our General Rules and each resolution passed by the Congress presented a true image of the future society. In place of our executive committee there would be a simple statistical and correspondence bureau; it would have to deal as best it knew with the independent sections, which are so independent that they can accept no steering authority, be it even one set up by their own free decision; for they would thus violate their primary duty—that of being a true model of the future society. Co-ordination of forces and joint action are no longer mentioned. If in each individual section the minority submits to the decision of the majority, it commits a crime against the principles of freedom and accepts a principle which leads to authority and dictatorship! If Stieber and all his associates, if the entire black cabinet, if all Prussian officers were ordered to join the Social-Democratic organisation in order to wreck it, the committee, or rather the statistical and correspondence bureau, must by no means keep them out, for this would amount to establishing a hierarchical and authoritarian organisation! And above all, there should be no disciplined sections! Indeed, no party discipline, no centralisation of forces at a particular point, no weapons of struggle! But what, then, would happen to the model of the future society? In short, where would this new organisation get us? To the cowardly, servile organisation of the early Christians, those slaves, who gratefully accepted every kick and whose grovelling did indeed after 300 years win them the victory of their religion—a method of revolution which the proletariat will surely not imitate! Like the early Christians, who took heaven as they imagined it as the model for their organisation, so we are to take Mr. Bakunin's heaven of the future society as a model, and are to pray and hope instead of fighting. And the people who preach this nonsense pretend to be the only true revolutionaries!70

This view cannot really be found in the Sonvilier Circular, but it follows from Engels’ assumptions about what was meant by the ideas of abstentionism, prefiguration, and the objections to the centralization of power in the General Council. Joint action is made impossible since there would be no executive committee to impose its will. Because we are aiming for a society that has abolished class conflict, we must therefore today act as if no conflicts exist and embrace complete pacifism, even in the face of abuse and attack, since any resistance to these acts of authority would themselves be authoritarian. This same line of reasoning is found throughout “On Authority” later, as I covered extensively in my critique.

Letters criticizing the Council continued to come in, with more sections following the Jura Federation’s lead in demanding a real Congress, to which Engels would respond with more sarcastic letters. Engels was becoming increasingly despondent and bitter, writing to Johann Becker on February 16, 1872:

These damned Italians make more work for me than the entire rest of the International put together makes for the General Council. And it is all the more infuriating as in all probability little will come of it as long as the Italian workers are content to allow a few doctrinaire journalists and lawyers to call the tune on their behalf.71

Engels did however find one surprising ally in Theodore Cuno, a German SDAP member who fled to Italy from police repression. Now living in Milan, Cuno was startled by the uproar around the Sonvilier Circular and wrote to Engels to try and figure out what was going on.72

Engels was all too happy to complain about Bakunin in his letter on January 24, and his response was covered in my critique of “On Authority” as it holds early versions of the arguments, repeating Engels’ mistakes about abstentionism and the anarchist theory of the state as having created capital. Engels also assures Cuno that, despite all evidence to the contrary, the workers of Italy were really on their side against Bakunin:

The Bakuninist press asserts that 20 Italian sections have affiliated with them; I have no knowledge of them. In any event, the leadership is in the hands of Bakunin's friends and adherents almost everywhere, and they are raising a terrific hubbub. But on closer examination it will most likely be found that they haven't much of a following, since in the final analysis the overwhelming mass of Italian workers are still Mazzinists and will remain so as long as the International is identified there with abstention from politics.

At any rate the situation in Italy is such that, for the present, the International there is dominated by Bakuninist intrigues. Nor does the General Council think of complaining about this; the Italians have the right to make fools of themselves as much as they please, and the General Council will oppose this only in peaceable debates.73

The “real movement” existing in Engels’ mind was firmly in his corner. However, Engels quickly lost this new ally as he was arrested and deported back to Germany on February 28, 1872.74

More and more places began demanding a new Congress and expressing their support for the Jura Federation. But while Engels had all but given up on Italy, Cafiero, once again, had to try and hold things together. But more and more Cafiero had begun to adopt a more neutral position on the Council, rather than directly defending it.75

The Neapolitan section was one of the few places in Italy to not have joined the Jura’s protest, and Cafiero could only follow Engels’ lead in pleading for people to wait for an official reply from the Council while also pleading with Engels to reply to his messages. But with no reply coming and increasing pressure, they began spreading the Sonvilier Circular themselves on January 30, 1872.76

By March 1872, Engels’ campaign in Italy was going nowhere. One of his other few operatives, Vitale Regis, wrote to him to say the cause was entirely lost.77 But this is not what Engels reported to the General Council, telling them on March 5th:

Citizen Engels announced that he had just received a letter from Italy which he had not time to translate, but from what he could see of it it was of a very favourable character indeed; it proved that the teachings of the pretended leaders—doctors, lawyers, journalists, etc.—had not any influence upon the real working class; the doctrine that they ought to abstain from politics found no favour with them.78

Engels was certain that the “real” working class (which apparently does not include doctors, lawyers, and journalists) was on their side. The regular denouncement of these categories of workers and the presentation of anarchists as “gang of declasses, the refuse of the bourgeoisie” is rather shocking to hear from Marx and Engels, being a journalist/private scholar and the son of a factory owner respectively.

Engels expanded on these alternative facts at their meeting the following week on March 12th, stating this:

Hitherto, all accounts received from the country, both by the correspondence of the Council and the newspapers of the Italian International, had represented the latter as unanimous in upholding the doctrine of complete abstention from political action, and in repelling the Conference resolution upon that subject. But it was not to be forgotten that both the correspondence and the newspapers, so far, had been in the hands, not of working men themselves, but of men of middle-class origin, lawyers, doctors, newspaper writers, etc. In fact, the great difficulty for the Council had been to open direct communications with the Italian working men themselves. This had now been done in one or two places, and now it was found that these working men, far from being enthusiastic for political abstention, were, on the contrary, very much pleased to hear that the General Council of the great mass of the International did not at all adhere to that doctrine. Thus it might be hoped that upon that question too the Italian working men would soon be found in harmony with those of the rest of Europe and the United States.79

Engels wanted to present this version of events where it only seemed like he had completely failed in Italy because of these “middle-class” individuals in control of the press. The actual people there were in contact with could therefore be dismissed on these grounds. But if only they could get past this “great difficulty,” Engels was certain he could find the “real movement,” who would no doubt support his own views.80

Things had not gotten any better for Engels by early May. Engels gives the same excuses again in another letter to Cuno, who was no longer in Italy:

The damned difficulty in Italy is simply getting into direct contact with the workers. These damned Bakuninist doctrinaire lawyers, doctors, etc., have penetrated everywhere and behave as if they were the hereditary representatives of the workers. Wherever we have been able to break through this line of skirmishers and get in touch with the masses themselves, everything is all right and soon mended, but it is almost impossible to do this anywhere due to a lack of addresses. That is why it would have been of great value for you to have remained in Milan…81

Had Engels actually used the people and resources that were available to him like Cafiero, had he not been so quick to admonish or write letters filled with sarcasm and contempt, had he not been so focused on denouncing Bakunin and dragging the Italians they were largely unaware of, had he worked with the people he was actually in contact with as secretary instead of looking for the secret “real workers” hidden away, perhaps Engels could have actually built up the allies he is complaining he lacks here. But we might as well say “had the London Conference never happened,” or “had they not treated the General Council as a governing body,” or “had Marx and Engels adopted an entirely different approach to Bakunin and federalism.” Had they not been authoritarian!

Real Splits in the International

The Council’s response to the Circular was delayed again and again, with continual promises that it was almost ready. While the Circular had been published in mid-November 1871, Marx presented his critique to the General Council on March 5, 1872, near the end of their meeting. It was written in French, which most of the Council members did not understand, but Marx moved for the text to be approved anyway so it could be published with the Council’s name attached. While Council members complained, it was approved nevertheless.82

Even after being approved though, things were delayed. While the Sonvilier Circular fit on a single double-sided piece of paper, Marx bragged that his response was as long as his book The Civil War in France. While I am sympathetic to long replies to short papers, obviously, they do not make for timely responses when people are demanding answers or voicing very real concerns. Technical difficulties delayed things even further though, much to Marx and Engels’ annoyance. It would not actually be published until the end of May, 1872.83

Marx and Engels had for a while now decided to dismiss any real serious ideological split forming, instead presenting the conflict with the anarchists as a personal issue, combatting the “sectarians” trying to sabotage the International and for Bakunin to set himself up as a dictator. Against the advice of others, the Fictitious Splits continued this on, largely focusing on Marx’s earlier attacks against Bakunin, often relying on misinformation and rumor, or attacking their call for “equalization of the classes” and views on inheritance. It was filled with invective like this:

The Alliance, which considers the resurrection of the sects a great step forward, is in itself conclusive proof that their time is over: for if initially they contained elements of progress, the program of the Alliance, in the tow of a “Mohammed without the Koran” [Bakunin], is nothing but a heap of pompously worded ideas long since dead and capable only of frightening bourgeois idiots or serving as evidence to be used by the Bonapartist or other prosecutors against members of the International.

It also contained some pretty blatant lies about the London Conference, such as claiming that the General Council had only a single delegate. In reality, 21 Council members were present, 6 with voting rights, and 6 more having made themselves the delegates of other nations. It made a very similar dismissal to the Circular’s view of a unity of means and ends, likewise claiming this was a religious view that believed “just as the medieval convents presented an image of celestial life, so the International must be the image of the New Jerusalem, whose ‘embryo’ the Alliance bears in its womb” and therefore “cast away all discipline and all arms.”84

If Marx and Engels had taken the ideological split seriously, they might have elaborated much more on the idea of federalism and free association, or the ways in which they believed that authoritarianism was necessary for liberation. Instead, we have this hand-waving and the standard contrast of Bakunin’s “sectarian movement” was again contrasted to Marx’s “real movement.”

The final chapters got especially personal with no obvious relevance to the Sonvilier Circular, describing how two of Bakunin’s friends, Albert Richard and Gaspard Blanc, had broken with him and now declared allegiance to Napoleon III, much to the outrage of Bakunin and the Jura Federation. Marx wanted to present this as, somehow, the natural conclusion of abstentionism.

These attacks did not impress Cafiero, who found it distasteful, writing to Engels:

And what about the Richard-Blanc affair? With what right does Marx, in relating that affair to the General Council, insinuate against all the individuals of a party, who do not share his opinions: ‘They had belonged to that party who had always preached abstention from politics’? Here, then, is revolutionary socialism in Europe in its entirety, transfigured by Marx into a hotbed of traitors!85

Fictitious Splits does have a very surprising ending though, marking one of the few places Marx spoke positively of anarchy and “all socialists” as working toward it:

Anarchy, then, is the great war horse of their master Bakunin, who has taken nothing from the socialist systems except a set of slogans. All socialists see anarchy as the following program:

Once the aim of the proletarian movement — i.e., abolition of classes — is attained, the power of the state, which serves to keep the great majority of producers in bondage to a very small exploiter minority, disappears, and the functions of government become simple administrative functions.

The Alliance draws an entirely different picture.

It proclaims anarchy in proletarian ranks as the most infallible means of breaking the powerful concentration of social and political forces in the hands of the exploiters. Under this pretext, it asks the International, at a time when the Old World is seeking a way of crushing it, to replace its organization with anarchy.

The international police want nothing better for perpetuating the Thiers republic, while cloaking it in a royal mantle.86

Marx therefore rejected the unity of means and ends proposed by the anarchists. For Marx, the only way to anarchy was through authoritarianism. Marx is also assuming that the criticism of the Sonvilier Circular is mainly a question about which idea would dominate in the IWA. A return to the pluralism which Resolution 9 had threatened would not be “to replace its organization with anarchy.”87

Instead of exculpating the Council as Engels had promised, Fictitious Splits only seemed to confirm people’s worst fears. A text by either Cafiero or Pezza on July 20, 1872 put it this way:

The General Council sought to hide an important question of principles under a heap of gossip and personal hostility which it had no shame in recounting, presenting it to the international public as a document of great importance.88

For Cafiero, the great defender of the Council, to write this kind of response involved a great change of heart. He had reached his breaking point.

While Engels seemed to have retained a positive impression of Cafiero for a good while, he thought little of his actual capabilities, especially in a country so thoroughly anarchistic. Engels wrote to Paul Lafargue, Marx’s son-in-law, on March 11, 1872: “They are all Bakunists in Naples, and there is only one amongst them, Cafiero, who at least is de bonne volonté [good-willed], with him I correspond.”89 Engels also wrote to Paul’s wife Laura on the same day that “Naples harbours the worst Bakuninists in the whole of Italy. Cafiero is a good chap, a born intermediary and, as such, naturally weak. If he doesn't improve soon, I shall give him up too.”90

Engels seemed to have no interest in using this “born intermediary” to intermediate though. Cafiero, the lone defender of the Council in Italy, continued to do his job even as Engels had given up. But it was precisely Cafiero’s “good-will” that inevitably lead him to give up on Engels. Palladino and a young Errico Malatesta invited Cafiero to meet Bakunin in person and make up for himself everything he had heard from Engels.91

On May 16th, Cafiero was still acting in the Council’s defense. He met Bakunin on the 20th. On the 21st, Bakunin wrote in his diary “All day with Fanelli and Cafiero - alliance accomplished.” Cafiero also wrote “After just a few minutes of conversation we both realized that there was the most complete agreement on principles. Yet they were the same principles I had been propagating for a year in Italy, without knowing that they were different from yours.” He ended up staying with Bakunin for a month, and by June had fully become an anarchist.92

On June 3rd he finished a letter to Engels, denouncing the General Council and the authoritarian communism of Marx and Engels. The Communist Manifesto especially was attacked along with Marx and Engels’ strategy for the conquest of political power.