No One Believes in the Non-Aggression "Principle"

A Critique of Rand and Rothbard's Circular Argument

Introduction: What is the NAP?

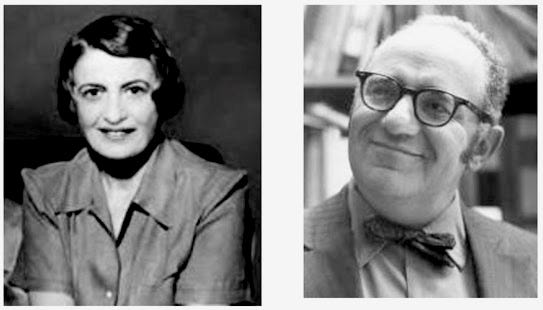

One of the main intellectual attractions for right-wing “libertarians,” more accurately referred to as “propertarians” for reasons that will be increasingly clear as I go on, is the promise of a consistent and systematic worldview. It is trying to create a “round universe,” fully explained, with the fundamental principles identified that hold the key to understanding everything else. Ethically, it is claimed that this is found in what is frequently referred to today as the “non-aggression principle,” or NAP for short. This idea also goes under the name “non-initiation principle” or “non-aggression axiom” as the concept was used by its two most famous proponents: Ayn Rand and Murray Rothbard.

The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism explains it like this:

The nonaggression axiom is an ethical principle often appealed to as a basis for libertarian rights theory. The principle forbids ‘aggression,’ which is understood to be any forcible interference with any individual’s person or property except in response to the initiation (including, for most proponents of the principle, the threatening of initiation) of similar forcible interference on the part of that individual.

The axiom has various formulations, but two especially influential 20th-century formulations are those of Ayn Rand and Murray Rothbard, who appear to have originated the term.1

There are two points worth calling out here.

Firstly, this axiom or principle is focused on the idea of “initiation of force” by an “aggressor.” This is meant to help distinguish the reactive use of force, as in cases of self-defense.

Second, it is meant to be working as the basis of propertarian rights theory. The idea of self-defense and justified cases of using violence is common to just about every ethical framework. What is meant to make the NAP unique is this is used as the foundation upon which the entire rest of the theory is built. If this is accepted, it is argued, it follows that no one may regulate or tax the use of someone else’s person or property, since this would require initiating force against them.

Not all propertarians make this argument, of course. It tends to be unpopular among ones that do not accept a more rights-focused ethical system, like Milton Friedman, or even by ones that do that are taken more serious academically like Robert Nozick. The NAP tends to be something largely concentrated to followers of Rand and Rothbard and the institutions they helped to influence, like the US Libertarian Party.

I will demonstrate here that the NAP is generally avoided by academia for good reason: the idea is flawed to its core and intellectually lazy. The entire concept is either contradictory or an uninteresting tautology. These issues are so fundamental to it, even its own supporters ultimately do not believe in it. To show this, I will first examine the concept as it was actually used by Rand and Rothbard before moving on toward a full critique.

Ayn Rand: The Non-Initiation Principle

Ayn Rand was a deeply anti-communist Russian-American science-fiction writer, who immigrated to the US to get away from the Soviet Union in 1926. Her novels were deeply ideological, presenting dystopian futures under the control of collectivist, altruistic, or communist opponents. These cartoonishly evil and/or cowardly people would then be opposed by brave men occasional woman that entirely agree with Ayn Rand, frequently breaking out into long monologues to explain her theories in full.

After the success of her novels The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged, she declared herself a philosopher. Not only that, she proclaimed herself the pioneer of a new philosophy she called “Objectivism” because, unlike other “subjectivist” theories from professional philosophers with real degrees that publish in peer-reviewed journals, her philosophy was objectively correct. Despite its obvious similarities to the philosophies of laissez-faire liberalism, Social Darwinism, and Nietzsche, Rand claimed in the appendix of Atlas Shrugged that “The only philosophical debt I can acknowledge is to Aristotle” for inventing formal logic, which was the only tool she needed to invent Objectivism.

The Textbook of Americanism

The first instance of the NAP I’m aware of comes from Rand’s 1946 article “The Textbook of Americanism.” In the aftermath of World War 2, Rand argued that the planet was divided between the forces of “individualism” that believe in certain inalienable rights, and the forces of “collectivism” which denied their existence. She associates the former with the United States (“Americanism”), and the latter with Soviet Russia and Nazi Germany.

But how do we know when a right has been violated? In the helpfully named section “How do we determine that a right has been violated,” she gives her answer:

A right cannot be violated except by physical force. One cannot deprive another of his life, nor enslave him, nor forbid him to pursue his happiness, except by using force against him. Whenever a man is made to act without his own free, personal, individual, voluntary consent - his right has been violated.

Therefore, we can draw a clear-cut division between the rights of one man and those of another. It is an objective division - not subject to differences of opinion, nor to majority decision, nor to arbitrary decree of society. NO MAN HAS THE RIGHT TO INITIATE THE USE OF PHYSICAL FORCE AGAINST ANOTHER MAN.2

We can see here a clear version of the “non-initiation principle,” and it is being explicitly presented as a way to determine if a right has been violated. This is the singular unifying principle that undergirds her entire theory of rights. The idea of “non-initiation” is logically prior to the idea of “rights,” and is what makes something a right in the first place. This is not merely an expression of support for the right of self-defense, but proposing this as a method from which the rest of our rights can be logically deduced. It is also worth noting here that what Rand is opposing here is the initiation of “physical force.” This will be important to keep in mind later when we examine the concept of “aggression” more closely.

Ayn Rand originally published the “Textbook of Americanism” in The Vigil, the newsletter for the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals (MPAPAI), of which she was on the executive committee for. This was a group of conservative Hollywood elites that believed Marxists were secretly conspiring to fill movies with anti-American messages to push a culture of Bolshevism on their audience. To fight this, guides like Rand’s textbook were meant to warn people how they should behave to be properly American if they didn’t wanted to be reported by the MPAPAI to the federal government’s House Un-American Activities Committee.3

Rand also submitted “Textbook” to Leonard Read’s newly established right-wing think tank, the Foundation for Economic Education (FEE). However, the non-initiation principle didn’t immediately catch on. Here is how Jennifer Burns describes in her biography on Ayn Rand Goddess of the Market:

The principle of noninitiation in particular appealed viscerally to Read. But most FEE friends were less enthusiastic. Rand had not spelled out or defended her basic premises, and much of what she wrote struck readers as pure assertion. “Her statement that these rights are granted to man by the fact of birth as a man not by an act of society, is illogical jargon,” wrote one, advising, “If Miss Rand is to get anywhere she must free herself from theological implications.” Another respondent was “favorably impressed by the goals which she seeks to attain, but the line of logic which she uses seems to me to be very weak.” Such readers though Rand left a critical question unanswered: Why did “no man have the right to initiate physical force”? Out of thirteen readers, only four recommended supporting the work in its present form.4

So Rand’s logic immediately was immediately questioned. Rather than actually build a rational case, she was simply asserting that this was how rights worked and how they could be deduced with no supporting argument. This will be a running theme with the NAP, which is taken by its supporters to be intuitively obvious, a basic presupposition of their worldview, the denial of which is taken as evil or absurd. Rand was similarly infuriated by this response. Metaphorically, she didn’t feel like playing anymore so she grabbed her ball and went home, writing to Read about how deep of an insult this was and demanding the names of the anonymous comments she received.5

Atlas Shrugged

The non-initiation principle would stick around as a central part of her work. When she published her novel Atlas Shrugged in 1957, it would appeared in the infamous 75 page long “John Galt” speech, one of the many long monologues given by characters in-story about how objectively correct Objectivism is, leaving all the villains of the story too stunned to speak as they patiently listen to it in its entirety. Here we can see the same hallmarks of the forbidding of the initiation of physical force:

Whatever may be open to disagreement, there is one act of evil that may not, the act that no man may commit against others and no man may sanction or forgive. So long as men desire to live together, no man may initiate—do you hear me? no man may start—the use of physical force against others.

To interpose the threat of physical destruction between a man and his perception of reality, is to negate and paralyze his means of survival; to force-him to act against his own judgment, is like forcing him to act against his own sight. Whoever, to whatever purpose or extent, initiates the use of force, is a killer acting on the premise of death in a manner wider than murder: the premise of destroying man’s capacity to live.

Rand spent two years writing and refining Galt’s speech, clarifying her ideas as well as trying to figure out how to fit what is in-universe a three hour long lecture into a story that was meant to be a fast-paced thriller novel. She did this to debatable success.

This speech was clearly her most cherished part of the book, laying out the core of her ideology. She would later reprint it by itself in her book For the New Intellectual (1961) with the tagline “This is the philosophy of Objectivism.”

For the New Intellectual

For the New Intellectual included several other self-published philosophical essays, including The Objectivist Ethics, in which she cites John Galt as if he were a real person:

Since I am to speak on Objectivist Ethics, I shall begin by quoting its best representative - John Galt, in Atlas Shrugged…

Ayn Rand intended to give in this essay a very complete view of ethics, going even beyond mere questions of rights. She tried to ultimately root her ethics in the concept of life as the ultimate standard of value. However, when she does discuss issues regarding rights, we see the non-initiation principle take center-stage once again:

The basic political principle of the Objectivist ethics is: no man may initiate the use of physical force against others. No man - or group or society or government - has the right to assume the role of a criminal and initiate the use of physical compulsion against any man. Men have the right to use physical force only in retaliation and only against those who initiate its use. The ethical principle involved is simple and clear-cut: it is the difference between murder and self-defense…

The only proper, moral purpose of a government is to protect man’s rights, which means: to protect him from physical violence.

Rand is retaining this view where we can determine what our rights are through the non-initiation principle.

We can also see how this is impacting the propertarian worldview. A frequent complaint among these laissez-faire liberals is about the existence of welfare states, or poor people claiming they have a right to housing, food, education, healthcare, public libraries, fire departments, postal services, public transportation, roads, etc. Not so, claims Rand. Your rights are only violated if someone initiates physical force against you, and the only role of government is in defending those rights.

Governments are institutional force, and the non-initiation principle gives us the one and only case where force may be appropriately used: in response to someone else initiating physical force. No other government service could ever possibly be ethically legitimate. There can be no regulation of actions (besides outlawing the initiation of physical force), and there can be no taxes, since these would both require the government to initiate physical force itself. Therefore, the only economic system compatible with ethics is, as Rand describes it, "full, pure, uncontrolled, unregulated laissez-faire capitalism - with a separation of state and economics, in the same way and for the same reasons as the separation of the state and church."

This idea of non-initiation also appears in For the New Intellectual’s introductory essay:

[T]here are two principles on which all men of intellectual integrity and good will can agree, as a “basic minimum,” as a precondition of any discussion, co-operation or movement toward an intellectual Renaissance. One principle is epistemological, the other is moral; they are not axioms, but until a man has proved them to himself and has accepted them, he is not fit for an intellectual discussion. These two principles are:

a. that emotions are not tools of cognition;

b. that no man has the right to initiate the use of physical force against others.

Rand’s assertion here that these are “not axioms” might be a swipe at Murray Rothbard who, as I mentioned earlier, defended a very similar concept he called the non-aggression axiom. It is irrelevant for my critique whether non-aggression is better understood as an axiom or as a basic minimum principle necessary to make intellectual discussion possible, so I will not dive into this question. Similar functions are being filled in either case.

Especially thanks to Atlas Shrugged, Rand was not only building a cult following, but actually built a literal cult with the tongue-in-cheek name “the Collective.”6 This was especially controlled by her top disciple and lover Nathaniel Branden. In 1958, the year after Atlas Shrugged was published, they worked together to establish the Nathaniel Branden Institute to promote Objectivism, which expanded past ethics to also include views of epistemology and art, as well as Branden’s own peculiar views of psychology where mental health was very strongly associated with ideological conformity to the “rationality” of Objectivism and the view that people were merely “bundles of premises”.7

This is where Murray Rothbard comes in.

Competition Between Rand and Rothbard

Murray Rothbard was a student of the Austrian School economist Ludwig von Mises, a fellow proponent of extreme laissez-faire capitalism. He formed his own pro-capitalism group called the Circle Bastiat, named after the 19th century French economist Frederic Bastiat. Like Rand (and unlike the utilitarian Mises), Rothbard was also deeply attached to a deontological approach to ethics, and credited Ayn Rand for introducing natural rights to him.

Rothbard was one of the people who really led propertarian efforts to appropriate the word “libertarian” away from anarchists. This was something he did knowingly and deliberately, as he comments in his book The Betrayal of the American Right, written in the early 1970s:

One gratifying aspect of our rise to some prominence is that, for the first time in my memory, we, “our side,” had captured a crucial word from the enemy… [Libertarians] had long been simply a polite word for left-wing anarchists, that is for anti-private property anarchists, either of the communist or syndicalist variety. But now we had taken it over.8

Rothbard wanted to take the word “anarchists” too, referring to himself as an “anarcho-capitalist" to describe his plan for privatized competing governments. Modern “anarcho”-capitalists are following in his footsteps.

Rothbard had met Rand a few times in the early 50s, and didn’t particularly like her from the start. Both were ideological purists, and the disagreements over Rothbard’s “anarcho”-capitalism was a major point of contention. Rand’s dominant personality and demand for strict ideological conformity from the members of her Collective disturbed him as well, especially from someone claiming to value individuality. While he credited Ayn Rand for introducing him to natural law theory, he dismissed the claimed originality of her discoveries, pointing to the many other natural law theorists that came before her. In a 1954 letter to Richard Cornuelle, he states that “the good stuff in Ayn’s system is not Ayn’s original contribution at all.”9

But after the publication of Atlas Shrugged in 1957, Rothbard started fanboying all over again, saying the book was "not merely the greatest novel ever written, [but] one of the very greatest books ever written, fiction or nonfiction."10 This was an olive branch to heal the divide between the two.

But as Rothbard was drawn into the Nathaniel Branden Institute, things would quickly turn sour. Using Objectivist psychological technique, Branden promised to cure his fear of travel, which kept him from leaving New York. In anticipation of being cured, he even signed up for an academic conference in Georgia where he would deliver a paper, titled The Mantle of Science, contrasting the approach to science in physics where there is no aspect of choice vs other areas like economics or ethics which need to account for free will.11

As part of Rothbard’s therapy, he was required to take a course in the Principles of Objectivism. He agreed, and signed up for it with his wife Joey, divulging deeply personal information to Branden. But when he missed the occasional lecture, he was treated to the third degree. Even worse, a major part of Branden’s diagnosis was advising Rothbard to divorce his wife for being Christian, whereas Objectivism was strictly atheist. Rothbard had also already begun identifying as an “anarcho”-capitalist, which Rand disagreed with, despite appearing to believe in something very functionally similar. These irrationalities could not be tolerated, and had to be at the root of his psychological issues according to Objectivist theory.

After he remained uncured after six months of “therapy,” Rothbard broke off the relationship entirely, canceling a debate that was scheduled between himself and Rand. Branden and Rand then called in Rothbard one final time, but now to accuse him of plagiarizing the paper he was going to deliver in Georgia. Things became extremely hostile, as Goddess of the Market recounts:

That evening’s mail brought a special delivery letter from Rand’s lawyer, outlining in detail the accusation of plagiarism and threatening a lawsuit against both Rothbard and the conference organizer, the German sociologist Helmut Shoeck.

The confrontation soon spilled out into open warfare between the Collective and the Circle Bastiat. George Reisman and Robert Hessen, formerly Rothbard loyalists, took Rand’s side in the plagiarism dispute… Filled in on the accusations, outsider like Schoeck, the National Review editor Frank Meyer, and Richard Cornuelle dismissed Rand and her group as “crackpots.” They found her accusations of plagiarism groundless. The ideas that Rand claimed as her own, Shoeck noted, had been in circulation for centuries. Still constrained by his phobia, Rothbard was unable to attend the conference as planned.12

Rothbard was deeply embittered towards Rand at this point, actually writing a play satirizing his own experience called Mozart was a Red. This time the rift would not heal, and in 1972 he was still denouncing Objectivism in his essay “The Sociology of the Ayn Rand Cult.” On the other side, Ayn Rand would consistently denounce Murray Rothbard and his followers of plagiarism, not only of that paper, but her ideas generally. Rand denounced the new “libertarian” movement, calling them the “hippies of the right.” Ten years after their break-up, when the Libertarian Party was founded, Rand was still mad:

Most of them [“libertarians”] are my enemies: they spend their time denouncing me, while plagiarizing my ideas. Now it’s a bad sign for an allegedly pro-capitalist party to start by stealing ideas.13

The Ayn Rand Institute still maintains this enmity to this day, as detailed in their FAQ:

The libertarianism we oppose is a specific set of ideas, the essence of which is a dedicated, thoroughgoing subjectivism. Libertarianism in this sense was spearheaded by Murray Rothbard and his followers in the 1960s and 1970s. Its political expression is anarchism, or “anarcho-capitalism” as they often term it, and a foreign policy of rabid anti-Americanism (which they pass off as “non-interventionism”).

The “libertarians,” in this usage of the term, plagiarize Ayn Rand’s non-initiation of force principle and convert it into an axiom, denying the need for and relevance of philosophical fundamentals — not only the underlying ethics, but also the underlying metaphysics and epistemology.

Personally, I do think that Rothbard’s argument around non-aggression was inspired by Rand. However, the Ayn Rand Institute is trying to have things both ways, claiming he both plagiarized her idea and that he transformed it into something different as an axiom. This is especially ironic given that Ayn Rand, as I mentioned before, refused to credit an intellectual debt to anyone except Aristotle for the invention of formal logic, despite the fact she is essentially presenting her own bastardized form of Locke, Spencer, and Nietzsche.

Murray Rothbard: The Non-Aggression Axiom

Like Rand, Rothbard thought his political theory could be reduced down to, and logically deduced from, this idea of non-initiation of force. While he described it as an axiom, it seems he did not care much how it was grounded, so long it was rigorously adhered to. Unlike Rand, Rothbard was content to avoid questions of epistemology or aesthetics, focusing instead on political philosophy and economics.

This would show up in his writings at least as far back as 1963, the earliest example I could find, from his essay War, Peace, and the State:

The fundamental axiom of libertarian theory is that no one may threaten or commit violence ("aggress") against another man's person or property. Violence may be employed only against the man who commits such violence; that is, only defensively against the aggressive violence of another. In short, no violence may be employed against a non-aggressor. Here is the fundamental rule from which can be deduced the entire corpus of libertarian theory.

[Footnote:] We shall not attempt to justify this axiom here. Most libertarians and even conservatives are familiar with the rule and even defend it; the problem is not so much in arriving at the rule as in fearlessly and consistently pursuing its numerous and often astounding implications.

While Rothbard is using slightly different language, we can clearly see that this is the same concept at play. Rothbard is introducing this language about aggression, identifying “violence” instead of “physical force,” and is also claiming that the rest of his theory can be deduced from this simple principle.

For a New Liberty

In 1973, two years after the Libertarian Party was established, Rothbard published his political treatise For a New Liberty: The Libertarian Manifesto. Close analysis of this book will be especially important for understanding the non-aggression principle, since it seems to be the place where it really took center-stage for propertarian discourse.

In it, he presents his core argument for propertarianism, and applies the idea to various areas of policy, including his own theory of “anarcho”-capitalism. Key to this argument was this idea of the non-aggression axiom, which he thought immediately established the core propertarian positions:

The libertarian creed rests upon one central axiom: that no man or group of men may aggress against the person or property of anyone else. This may be called the ‘nonaggression axiom.’ ‘Aggression’ is defined as the initiation of the use or threat of physical violence against the person or property of anyone else. Aggression is therefore synonymous with invasion.

Rothbard argued that this principle led him to take on a mixture of left-wing and right-wing positions. On the Left, it implied a support for certain civil liberties, such as freedom of speech and assembly, as well as an opposition to conscription, all important issues in the middle of the US-Vietnam War. On the Right, like Rand, he also believed it also established sufficient support for extreme laissez-faire capitalism, since all regulations or taxation would be aggression against others’ property by the government. Rothbard took pride that “the libertarian sees no inconsistency in being ‘leftist’ on some issues and ‘rightist’ on others. On the contrary, he sees his own position as virtually the only consistent one, consistent on behalf of the liberty of every individual.”

Between these two, Rothbard’s commitment to “Left” positions is extremely questionable. Where are people meant to have these civil liberties? Rothbard opposed the existence of public land, and he believed property owners absolutely could regulate the speech and assembly rights of people on their property. As he would put it himself, all rights ultimately reduce to property rights for him. As he put it in his 1970 book Power and Market:

[A]lleged “human rights” can be boiled down to property rights, although in many cases this fact is obscured. Take, for example, the “human right” of free speech. Freedom of speech is supposed to mean the right of everyone to say whatever he likes. But the neglected question is: Where? Where does a man have this right? He certainly does not have it on property on which he is trespassing. In short, he has this right only either on his own property or on the property of someone who has agreed, as a gift or in a rental contract, to allow him on the premises. In fact, then, there is no such thing as a separate “right to free speech”; there is only a man’s property right: the right to do as he wills with his own or to make voluntary agreements with other property owners.

Thus, for people who do not own property, specifically land, no right to free speech exists. While Rothbard wanted to publicly make it seem like he and his new Libertarian Party was rising above this left-right paradigm, just like he believed human rights boil down to property rights, his “Left” positions boil down to his Right ones. The only rights are property rights. If you do not own property, you have no rights. Where would you have them?

Returning to For a New Liberty, Rothbard takes this argument in a very strange direction though:

If the central axiom of the libertarian creed is nonaggression against anyone’s person and property, how is this axiom arrived at? What is its groundwork or support? Here, libertarians, past and present, have differed considerably. Roughly, there are three broad types of foundation for the libertarian axiom, corresponding to three kinds of ethical philosophy: the emotivist, the utilitarian, and the natural rights viewpoint.

It is odd to ask how we “arrive” at an axiom and what “groundwork” it has. Generally speaking, if we need to demonstrate something, it isn’t an axiom. Axioms are simply taken to be true, either for the sake of argument or as something self-evident. They do not require proof, and are the groundwork from which a proof is constructed.

Rothbard also doesn’t seem to be attempting to prove the non-aggression axiom here. He goes on to reject emotivism and utilitarianism as inadequate defenders of the non-aggression axiom, therefore endorsing a natural rights approach. So rather than using these moral frameworks to arrive at his “axiom,” he is using his axiom to arrive at his moral framework. This is an odd way of presenting things, but seems consistent with some attempt at using the non-aggression principle to establish what our rights are.

Rothbard’s approach from here seems much more questionable. For a natural rights approach, he tries to divide things up into two questions: ownership of human persons and ownership of non-human objects. (Remember, for Rothbard, all questions of rights reduce to property rights, which is why these are all questions of “ownership.”)

Taking up ownership of persons, he defends his stance of self-ownership, which is “the absolute right of each man, by virtue of his (or her) being a human being, to ‘own’ his or her own body; that is, to control that body free of coercive interference.” His argument in favor of self-ownership is that, if we were to deny it, we would be left with two other absurd positions he wants to dismiss, leaving it as the correct answer by process of elimination:

Consider, too, the consequences of denying each man the right to own his own person. There are then only two alternatives: either (1) a certain class of people, A, have the right to own another class, B; or (2) everyone has the right to own his own equal quotal share of everyone else. The first alternative implies that while Class A deserves the rights of being human, Class B is in reality subhuman and therefore deserves no such rights. But since they are indeed human beings, the first alternative contradicts itself in denying natural human rights to one set of humans.

…

The second alternative, what we might call “participatory communalism” or “communism,” holds that every man should have the right to own his equal quotal share of everyone else. If there are two billion people in the world, then everyone has the right to own one two-billionth of every other person. … [W]e can picture the viability of such a world: a world in which no man is free to take any action whatever without prior approval or indeed command by everyone else in society. It should be clear that in that sort of “communist” world, no one would be able to do anything, and the human race would quickly perish.

Why is Rothbard arguing for things this way though? Surely he has a much quicker alternative available to him: the non-aggression axiom. It clearly states that “no man or group of men may aggress against the person or property of anyone else.” If we are taking this seriously as axiomatically true, then that already forbids coercive interference against someone else’s body. No further proof necessary.

This argument is also silly independently from anything about the non-aggression axiom too, since it overlooks plenty of other alternatives or mixtures of these systems. Rothbard is working with false trichotomies. Furthermore, it faces the same issue as free speech. Where are people meant to have a right of self-ownership?

Rothbard’s reasoning might be made a bit more clear when we consider his argument for the ownership of non-human objects.

A more difficult task is to settle on a theory of property in nonhuman objects, in the things of this earth. It is comparatively easy to recognize the practice when someone is aggressing against the property right of another’s person: If A assaults B, he is violating the property right of B in his own body. But with nonhuman objects the problem is more complex. If, for example, we see X seizing a watch in the possession of Y we cannot automatically assume that X is aggressing against Y’s right of property in the watch; for may not X have been the original, “true” owner of the watch who can therefore be said to be repossessing his own legitimate property? In order to decide, we need a theory of justice in property, a theory that will tell us whether X or Y or indeed someone else is the legitimate owner.

Because of this problem, Rothbard needs to go on a lengthy argument around how property rights are meant to be established, essentially presenting a very simplified version of Lockean homesteading theory, as our personality becomes “mixed” with objects we labor on. He even block quotes Locke at length.

But what about the non-aggression axiom? Why aren’t we looking at aggression to see where property rights begin and end?

Well, because Rothbard doesn’t want to. If we were to apply his non-aggression axiom as an actual test for rights, it would lead to a conclusion that Rothbard cannot accept: that it would be wrong for X to seize a watch in Y’s position, even if X had been the previous possessor. That is a logically consistent stance he could take, but it strikes him as unacceptable.

Rothbard isn’t using the non-aggression axiom here to establish what legitimate property is. He is using a completely separate theory of property to interpret what he is deciding to count as aggression against “legitimate” property, i.e. legitimized by something other than the non-aggression axiom!

This is circular reasoning. Rothbard used the truth of the non-aggression axiom to demonstrate that natural law theory must be correct, but the non-aggression axiom itself needs presupposes the truth of natural law.

Imagine if the other ethical theories had simply declared that something only counts as aggression if it violates their system. If a utilitarian argued something is only “aggression” if it reduces net utility, then they are not the inadequate defenders Rothbard made them out to be. A utilitarian could defend the non-aggression axiom in every single case because they are just defining aggression in a way to match their ethical theory. They wouldn’t be excusing aggression when it contradicts utilitarianism because those cases wouldn’t count as aggression in the first place.

This analysis is quickly moving us into the next topic, explaining why the NAP is a flawed concept to its core.

The Critique of the NAP

Both theories of the Non-Aggression Principle promise three main features.

The NAP forbids the initiation of force, i.e. aggression, no matter what.

Our rights can all be deduced from the NAP.

Consistently applying the NAP to everything, including the government, produces an extreme propertarian position (e.g. laissez-faire capitalism, no regulation, no taxes, etc.).

The real questionable part around the NAP is how “aggression” or the “initiation of physical force” is understood. Depending on how this idea is presented, the NAP will ultimately either be wrong, circular, or tautological.

With Rothbard, we clearly see an issue of circularity. Rothbard tried to use the non-aggression axiom to prove natural rights theory was correct, and then he used natural rights theory to determine what gets to count as aggression. Rothbard is not deducing our rights from the NAP, but instead simply presupposes a certain outcome hidden within how he defines “aggression.” If we assumed an entirely different list of rights, the non-aggression axiom would change along with it and would be useless in correcting things.

Rothbard would have done better to replace any idea of the “initiation of force” with the “violation of rights.” At least in that case, there would be no pretending that the list of rights is being deduced from this principle. Although, if we are discussing concepts this broad, it seems like we’d do even better to appeal to some other ethical tautology like the “do good” principle or the “don’t do evil” axiom.

Rand’s definition does little better. Talking about “physical force” instead of aggression sounds more specific, and calls to mind much more explicit actions like punching, kicking, biting, burning, shooting, etc. Forbidding the initiation of these sorts of actions sounds more useful if we did want to deduce some list of rights.

However, Rand clearly did not actually believe this herself. For one thing, she and other Objectivists would readily admit there are times when it is acceptable to initiate physical force, such as in a boxing match. Does her principle forbid either boxer from throwing the first punch? Of course not, because she has in mind involuntary or nonconsensual initiations of physical force. She left that important detail out of any formulation of her principle. Since she failed to mention it, let’s also throw in the threat of physical force there too.

Even if we modify her principle this way though, it does little good precisely for the reasons Rothbard didn’t use it. There are plenty of actions Rand believe violate rights that do not initiate physical force, and there are actions that do not violate rights which nevertheless initiate physical force. As Rothbard pointed out in his example, if X tries to take a watch on Y’s wrist, then X is the one initiating physical force. But if X is the legitimate owner, does Rand oppose this action? Will she chide X for trying to reclaim his property because he initiated nonconsensual physical force?

No, of course not. She could not arrive at her desired system of laissez-faire capitalism unless she believed in the government violently enforcing property claims. The truth is that, much like Rothbard, she is just hiding under the name “physical force” everything she thinks counts as a rights violation, including non-physical non-force actions like fraud. This oddity is mentioned in the Goddess of the Market biography on Ayn Rand:

Although it sounded straightforward, Rand’s definition of force was nuanced. She defined fraud, extortion, and breach of contract as force, thus enabling government to establish a legal regime that would create a framework for commerce. Critically, Rand also considered taxation to be an “initiation of physical force” since it was obtained, ultimately, “at the point of a gun.” This led her to a radical conclusion: that taxation itself was immoral.

Neither Rand nor Rothbard actually believed what they were saying. Or rather, they might have believed it, but in effect only engaged in a giant exercise of confirmation bias. Their faith in capitalism was so strong, so normalized, and so intuitive to them that they believed a simple ban of “physical force” or “aggression” would obviously lead to their system. They looked into a mirror and didn’t realize they saw a reflection.

It seems like any other attempt at formulating a non-aggression principle would be similarly doomed. If aggression is defined in terms of rights, then we cannot use the concept to establish a proper system of rights. If we try to take the NAP seriously as a principle from which we can deduce a system of rights, then it is clearly wrong. If we instead treat it as a law against violating ethical rights, then it is a tautology since, if such rights exist, then it is by definition wrong to violate them. The only path available is the one Rand and Rothbard used: using a circular argument, jumping back and forth between these two views according to whatever is rhetorically useful in the moment.

Propertarians Debating the NAP

Some propertarians have realized the issue of this critique themselves, and therefore reject the NAP, even while remaining closely aligned with Rothbard or Rand.

Matt Zwolinski, the founder of Bleeding Heart Libertarians, explicitly pointed out some of these flaws in his 2013 article “Six Reasons Libertarians Should Reject the Non-Aggression Principle.” While I do not think all of his objections work, this one essentially agrees with the case I have made:

Parasitic on a Theory of Property – Even if the NAP is correct, it cannot serve as a fundamental principle of libertarian ethics, because its meaning and normative force are entirely parasitic on an underlying theory of property. Suppose A is walking across an empty field, when B jumps out of the bushes and clubs A on the head. It certainly looks like B is aggressing against A in this case. But on the libertarian view, whether this is so depends entirely on the relevant property rights – specifically, who owns the field. If it’s B’s field, and A was crossing it without B’s consent, then A was the one who was actually aggressing against B. Thus, “aggression,” on the libertarian view, doesn’t really mean physical violence at all. It means “violation of property rights.” But if this is true, then the NAP’s focus on “aggression” and “violence” is at best superfluous, and at worst misleading. It is the enforcement of property rights, not the prohibition of aggression, that is fundamental to libertarianism.

Zwolinski is absolutely correct here, as I demonstrated. This prompted a bit of discussion in propertarian circles, pointing out areas of Zwolinski’s argument that were genuinely sloppy or unclear.

Julian Sanchez, another propertarian, supported Zwolinski in this area in his article “The Non-Aggression Principle Can’t Be Salvaged - And Isn’t Even a Principle”:

The NAP is no help deciding the questions you’re attempting to answer at this level, because as Zwolinski notes, it’s parasitic on theories of property and coercion that reside at this same level of abstraction. You can’t resolve a philosophical debate between a classical liberal and a socialist by appealing to the NAP, because each can claim their view is consistent with that principle given their theories of property: The state is not “aggressing” on an individual “property owner” if in fact The People ultimately own (or have some kind of share right in) all property, given the normatively loaded way “aggression” is used here. The appeal of the NAP lies in its apparent simplicity and intuitive plausibility (tautologies tend to be intuitively plausible), but it’s typically deployed in a way that amounts to a kind of shell game: I argue that socialism must be rejected on the grounds that it violates this one simple moral principle, and hope my interlocutor doesn’t notice that I’ve essentially begged the question by baking a theory of strong property rights incompatible with socialism into my conception of “aggression,” when of course libertarian property rights are ultimately backed by the threat of (individual or state) violence as well.

In the face of these objections, David Gordon at the Mises Institute is only able to put up this flimsy response in his article “In Defense of Non-Aggression”:

In brief, there are non-rights based moral theories. The NAP, by tying the use of force to rights-violations, rules out using force to achieve moral goals not founded on persons’ claims. It is thus not a tautology.

Sanchez might answer that the NAP adds nothing to “People have rights” or a list of these rights. These already exclude moral theories not based on rights. This answer is also not correct. Someone who favored the wealth transfer might say that enough of an increase in utility overrides the billionaires’ property rights; the billionaires can be forced to transfer their wealth if they don’t want to do it. Again, this isn’t to say that the poor have a right to the transfer. Some moral theories include both rights and other considerations as well that justify using force. The NAP blocks using force that doesn’t respond to a rights violation, so it does add to “People have rights.”

Sanchez is correct that the NAP doesn’t by itself block a theory that includes non-libertarian rights, but this doesn’t make it useless for libertarians. The NAP doesn’t do everything, but it does do some things.

Gordon is basically claiming that, while it is true the NAP does not and cannot be used to determine what our rights are, it at least implies that a rights-based theory of ethics is correct. This ties into how Rothbard actually used his non-aggression axiom within For a New Liberty.

My response is simple: No it doesn’t. If we can hook up the NAP to a set of non-propertarian rights, then we can also hook it up to a null set. The NAP doesn’t establish the existence of rights. All it would tell us, as a tautology, is that if rights exist, that if a rights-based ethical framework is correct, then we should not violate those rights. But this already follows from the definition of “rights” in this context. The NAP is adding nothing. It is, as Sanchez argued, just a shell game.

What Should We Take Away?

As some propertarians have finally come around to understanding, the NAP cannot be used as the foundation of their system. Even as they use it themselves, as Sanchez pointed out, it is not even a principle.

As a genuine anarchist defending genuine libertarianism (i.e. socialism), propertarianism must be opposed anywhere and everywhere. It is a theory born in deception, misrepresenting itself not only in name but in argument. Rand and Rothbard did not innovate even this misrepresentation, even if they might have added a new spin. Liberalism itself is fundamentally an ideology meant to counterfeit or mislead people away from true worker emancipation. The Italian anarchist Errico Malatesta put that well in his essay “Anarchy”:

The methods from which the different non-anarchist parties expect, or say they do, the greatest good of one and all can be reduced to two, the authoritarian and the so-called liberal. […] The latter relies on free individual enterprise and proclaims, if not the abolition, at least the reduction of governmental functions to an absolute minimum; but because it respects private property and is entirely based on the principle of each for himself and therefore of competition between men, the liberty it espouses is for the strong and for the property owners to oppress and exploit the weak, those who have nothing; and far from producing harmony, tends to increase even more the gap between rich and poor and it too leads to exploitation and domination, in other words, to authority. This second method, that is liberalism, is in theory a kind of anarchy without socialism, and therefore is simply a lie, for freedom is not possible without equality, and real anarchy cannot exist without solidarity, without socialism. The criticism liberals direct at government consists only of wanting to deprive it of some of its functions and to call on the capitalists to fight it out among themselves, but it cannot attack the repressive functions which are of its essence: for without the gendarme the property owner could not exist, indeed the government’s powers of repression must perforce increase as free competition results in more discord and inequality.

Anarchists offer a new method: that is free initiative of all and free compact when, private property having been abolished by revolutionary action, everybody has been put in a situation of equality to dispose of social wealth. This method, by not allowing access to the reconstitution of private property, must lead, via free association, to the complete victory of the principle of solidarity.

I wish propertarians the best in struggling with the flaws of their own thinking and argument in the hope that, in treating these issues seriously, they will find the more foundational errors of their worldview.

This is not to say that the concept of distinguishing between aggression and non-aggression is useless. This is a distinction so common and universal I cannot even say it too has been lifted from anarchism, although we can certainly find anarchists using similar divisions. For example, Alexander Berkman argues this within his book Now and After: The ABC of Communist Anarchism:

Anarchism is opposed to any interference with your liberty, be it by force and violence or by any other means. It is against all invasion and compulsion. But if any one attacks you, then it is he who is invading you, he who is employing violence against you. You have a right to defend yourself. More than that, it is your duty, as an Anarchist, to protect your liberty, to resist coercion and compulsion. Otherwise you are a slave, not a free man. In other words, the social revolution will attack no one, but it will defend itself against invasion from any quarter.

The mistake of the propertarians was not that they distinguished between aggression and non-aggression, as just about everyone including anarchists have done, but to think that they could deduce their entire theory merely on this concept of self-defense alone, without reference to anything else. Anarchists like Malatesta and Berkman do not begin with non-aggression, but with a developed view of freedom, equality, and solidarity together with class analysis of modern society and the systems of domination and exploitation upon which it is built.14

Thanks for reading! If you would like to support me, you can help buy me a Ko-Fi!

Ronald Hamowy, The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism, p. 357

Ayn Rand, “Textbook of Americanism”, p. 10

Jennifer Burns, Goddess of the Market, p. 118

Ibid., p. 119

Ibid., p. 119

Ibid., p. 144

Ibid., p. 153

Murray Rothbard, The Betrayal of the American Right, p. 83

Goddess of the Market, p. 153

Murray Rothbard, Letter to Ayn Rand, October 3, 1957

Goddess of the Market, p. 182-83

Ibid., p. 184

Ayn Rand Lexicon, “What was Ayn Rand’s view of the libertarian movement?”

For more on how anarchists understand authority and distinguish it from resistance to that authority, see my paper Read On Authority.

Interesting read. I had this same issue myself when trying to understand the non-aggression principle; what is aggression? Socialists see the Capitalist having full control over the means of production to be aggression, and Conservatives see violation of traditional morality as aggression against the nation as a whole.

So the NAP has to derive from something else. Rothbard seems to derive it from property rights, which I think is ridiculous since property rights have to be derived from another idea, i.e. individual rights.