Socialism and Equality

Equality is perhaps the virtue most strongly associated with socialism and left-wing politics in the public eye. According to this 2018 Gallup poll, it literally is. Plenty of socialists will proudly present themselves as champions of equality, denouncing capitalism for its inequality. Likewise, opponents of socialism like to put a nefarious spin on equality, talking of “leveling” and the destruction of individuality. It is argued that socialism represents the sacrifice of freedom in the name of equality.

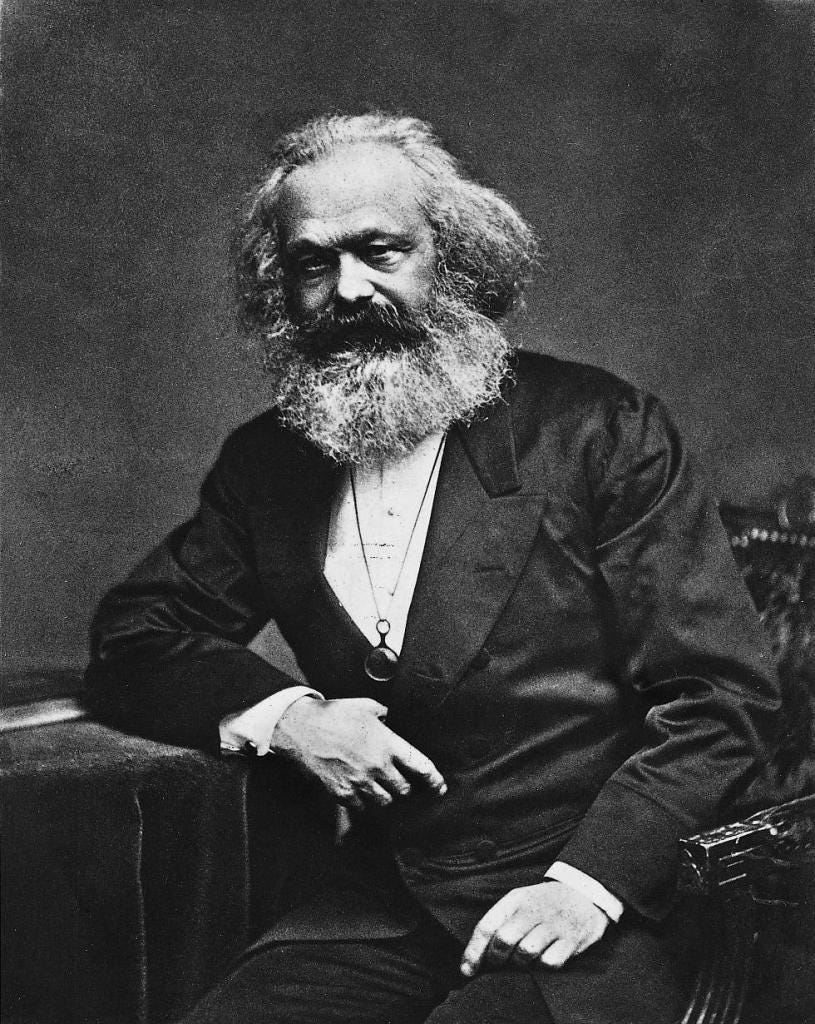

It might surprise socialists and anti-socialists alike that Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels generally opposed this association. They considered it misleading at best and frequently an inaccurate way of looking at communism. This has been covered well in Zoe Baker’s video Marx and Engels Were Not Egalitarians, as well as Jonas Čeika’s video Why equality is unhelpful as a political goal. Both videos describe ways in which Marx and Engels were critical of calls for equality, rejecting it as a social ideal, preferring to describe their primary aim as abolishing class rule.

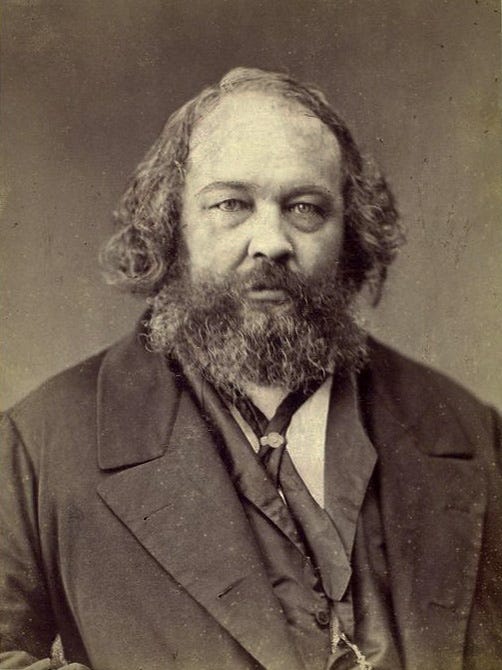

Perhaps again challenging popular stereotypes, anarchists like Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and Mikhail Bakunin, so well-known for championing individual liberty, who tended to emphasize the deeper connection between freedom and equality. In fact, one of the first major breaks between Marx and Bakunin in the First International occurred over a dispute on equality.

To better understand this, it is worth examining the arguments and objections from each party so that we can evaluate them on their merits. I can, of course, only speak on this to the extent I am familiar with their writings, and leave open the possibility that there may be further discussion on these subject in works I have not read.

Proudhon: Defender of Equality

Society, Justice, and Equality Against Property

Proudhon very proudly placed himself on the side of equality:

A defender of equality, I shall speak without bitterness and without anger; with the independence becoming a philosopher, with the courage and firmness of a free man. May I, in this momentous struggle, carry into all hearts the light with which I am filled; and show, by the success of my argument, that equality failed to conquer by the sword only that it might conquer by the pen!

This quote is from his most famous work What is Property (1840), which I recently summarized each chapter of in detail. In it he defends his answer to the question posed in his title: Property is theft! He does this firstly by debunking various defenses offered in favor of property, especially those grounded in rights of occupancy or labor, showing why property is contradictory and self-undermining as a system and is therefore “impossible,” and finally presenting the foundation of his own theory of justice that he argued we must and are moving toward.

Equality is central to his argument against property. His main strategy is to demonstrate how arguments in favor of property must presuppose some idea of equality for their justification, but by applying this standard consistently we are led to reject property as an inequality. Likewise, to show that property is impossible, he shows how social harmony depends on equality, meaning any system built on property will be thrown into chaos and conflict. He recognizes this explicitly as his strategy in chapter 5:

On the one hand, the idea of justice being identical with that of society, and society necessarily implying equality, equality must underlie all the sophisms invented in defence of property; for, since property can be defended only as a just and social institution, and property being inequality, in order to prove that property is in harmony with society, it must be shown that injustice is justice, and that inequality is equality, — a contradiction in terms. On the other hand, since the idea of equality — the second element of justice — has its source in the mathematical proportions of things; and since property, or the unequal distribution of wealth among laborers, destroys the necessary balance between labor, production, and consumption, — property must be impossible.

For anyone interested in the greater details of this argument, I recommend looking at my plain-language summary of his works.

Connecting this all together, what we see time and time again in this analysis is that in both matters of production and distribution, exploitation breaks down social bonds and turns people against each other. The control over resources as property allows some to live off the labor of others, to live without working, indicating they do not actually exist as associates, but as enemies.

The Nature of Equality and Equality of Nature

Equality has been associated with justice for thousands of years. Aristotle argued in his Nicomachean Ethics that “If, then, the unjust is unequal, just is equal, as all men suppose it to be, even apart from argument.” The reason for this is simple. Justice is meant to give each their due, establishing a kind of proportionality, and therefore an equality, between what is owed and what is received. Different notions of justice however will give different standards by which this proportionality is meant to be judged. This was, again, recognized by Aristotle:

[A]wards should be 'according to merit'; for all men agree that what is just in distribution must be according to merit in some sense, though they do not all specify the same sort of merit, but democrats identify it with the status of freeman, supporters of oligarchy with wealth (or with noble birth), and supporters of aristocracy with excellence.

On these grounds, Aristotle actually upheld slavery as just, saying that some people were “natural slaves” and that this legal status was therefore proportionate to them. What strikes us as a monstrous injustice and inequality was for him a kind of equality, at least when applied to these “natural” slaves.1

To say that we want justice, and therefore equality, is easy. But the difficulty posed here is “equality of what?” We cannot make different people equal in every single respect. Otherwise they would not be different people. To follow the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy’s entry on equality, we can distinguish between “equality” and “identity”:

‘Equality’ (or ‘equal’) signifies correspondence between a group of different objects, persons, processes or circumstances that have the same qualities in at least one respect, but not all respects, i.e., regarding one specific feature, with differences in other features. ‘Equality’ must then be distinguished from ‘identity’, which refers to one and the same object corresponding to itself in all its features.

Proudhon was aware of this difficulty, and was not simply calling for equality in the abstract, without reference to any particular feature. In fact, he called out the French government for failing to fully account for this themselves in chapter 1 of What is Property:

Bias and prejudice are apparent in all the phrases of the new legislators. The nation had suffered from a multitude of exclusions and privileges; its representatives issued the following declaration: All men are equal by nature and before the law; an ambiguous and redundant declaration. Men are equal by nature: does that mean that they are equal in size, beauty, talents, and virtue? No; they meant, then, political and civil equality. Then it would have been sufficient to have said: All men are equal before the law.

But what is equality before the law? Neither the constitution of 1790, nor that of ’93, nor the granted charter, nor the accepted charter, have defined it accurately. All imply an inequality in fortune and station incompatible with even a shadow of equality in rights. In this respect it may be said that all our constitutions have been faithful expressions of the popular will: I am going to prove it.

Proudhon is not just murmuring “equality, equality.” When he did advocate equality, he had a particular thing in mind. Or rather, he has a number of things working as a complete network of equality. There is equality before the law, but this type of equality is premised on still other forms of equality, like in fortune or station. As he goes on, this will also include equality of wealth, wages, labor, possessions, and liberty. There is some justification then in calling himself a defender of “equality” without qualification since he is implicitly referring to this interconnected system.

When Proudhon advocates for equality, he above all has in mind a kind of equality with respect to material wealth. He did not believe this equality could or should be applied in every respect, especially in matters of how we treat others. As he put it, the latter is a matter of esteem, and it is a virtue that is proportionate or relative to people’s particular forms of excellence. It is acts of benevolence by the strong, gratitude from the weak, and friendship between equals in terms of strength, skill, courage, etc.

The Basis of Socialist Equality

We have seen that Proudhon believed that society, justice, and equality were all fundamentally connected, expressing themselves in various ways. He especially focused on the distribution of material goods in this regard, distinguishing this from immaterial goods like esteem which may be distributed unequally according to certain standards of merit.

In the conclusion of What is Property, Proudhon tries to bring this all together to form a full system of Liberty, which he argues is based upon four principles:

Now, if we imagine a society based upon these four principles, — equality, law, independence, and proportionality, — we find: —

1. That equality, consisting only in equality of conditions, that is, of means, and not in equality of comfort, — which it is the business of the laborers to achieve for themselves, when provided with equal means, — in no way violates justice and équité.

[…]

4. That proportionality, being admitted only in the sphere of intelligence and sentiment, and not as regards material objects, may be observed without violating justice or social equality.

This third form of society, the synthesis of communism and property, we will call liberty.

This summary gives us a look at the main idea of equality, in contrast to the many different particular applications of equality we see earlier in the book. This is equality of conditions, of means. In other words, this equality is a matter of our relation to the means of production. Proudhon seems to believe there should also be some “equality of comfort,” but this is treated as a secondary matter that workers must figure out for themselves.

Proudhon’s thought on equality is incredibly broad, and is applied in a number of ways which I am not diving into completely here. For example, he has advocated a kind of “equality of wages” which might strike some socialists as odd, but there is some complexity and nuance here which I cover partly in my summary of chapters 3 and 4 of What is Property. To speak more fully on this, I would need deeper familiarity with his work. For now we may treat this “equality of comfort” as secondary just as Proudhon has here, as this would be a derivative notion of equality.

There are also some additional complexities since Proudhon believed society was so closely associated to equality that even inequalities can be described as kind of equalities insofar as they strive after maintaining these kinds of social relationships. Property for example is seen as one of the ultimate inequalities, as he makes quite clear throughout What is Property. Yet in the final section of chapter 2 on Civil Law justifications, he argues that property was introduced and justified as a system as a way to fix certain inequalities and preserve certain equal distributions.

But, indeed, what guide did the law follow in creating the domain of property? What principle directed it? What was its standard?

Would you believe it? It was equality.

However we interpret Proudhon here, it is clear that he thinks these other forms of equality are extending from a more fundamental equality, namely found in the collective ownership of the means of production. As society and equality are ultimately identical, to relate to one another as associates it to relate as equals. Socialism, a truly social relation, can and must be based on equality, and this begins with in terms of material goods with what makes the production of these goods possible.

Marx and Engels Against Equality

In stark contrast to Proudhon, Marx and Engels not only did not emphasize equality in their writings, but tended to push back against appeals to equality made by others. Equality is largely seen as a bourgeois value, derived especially from the exchange of equal values in the market. Even outside of that, they also tend to put forward two major criticisms. Firstly, absolute equality is seen as impossible, since it would require people to be identical. Secondly, they analyze the way which different, and presumably any, system based on equality must ultimately be reductive according to the standard this equality is measured by, and will therefore lead to harmful inequalities in other respects.

Their discussion of equality therefore tends to be fairly negative or dismissive. When the proletariat does demand equality, this is seen as an inexact and sometimes inaccurate way of expressing their real revolutionary instinct for their true goal: the abolition of classes. The accepted forms of discussing equality are therefore seen in either objecting to inequalities that result from class distinctions, or turning the appeals to equality made by the bourgeoisie back against them.

Apparently missing from their treatment is any recognition that class distinctions themselves are a kind of inequality, and that their abolition in favor of the collective ownership of the means of production is establishing a kind of equality, as Proudhon had pointed out. This appears like an unavoidable conclusion as well. To abolish a distinction, to get rid of a difference, is to end an inequality, and therefore makes people equal in that respect. Within this collective ownership, people hold the same, and therefore an equal, relationship to the means of production. The association which this socialism is built must be on inequality.

Marx and Engels generally do not deny that they are advocating for a kind of equality, but if they recognized they were doing this, they certainly did not take any effort to make this clear either. Whenever the proletarian demand is discussed, they substitute their own phrase, and try to distance themselves from equality as a French value which they present themselves as surpassing by revealing its “true” meaning, or a bourgeois value which must be abandoned. This hesitancy is also likely connected to Marx and Engels’ tendency to distance themselves from making a moral critique, and therefore avoiding terms that evoked a sense of justice or right as fundamental to their worldview.

Engels’ Letter to August Bebel

We can see this tendency clear in Engels and Marx’s critiques of the United Workers’ Party of Germany’s drafted “Gotha Programme.” While Marx’s response is far more famous, Engels addressed many of his own problems with the programme in a letter to August Bebel from March 1875. Among other problems, he took issue with the programme’s explicit call for equality:

"The elimination of all social and political inequality,” rather than “the abolition of all class distinctions,” is similarly a most dubious expression. As between one country, one province and even one place and another, living conditions will always evince a certain inequality which may be reduced to a minimum but never wholly eliminated. The living conditions of Alpine dwellers will always be different from those of the plainsmen.

This is a non sequitur. The Gotha Programme did not call for absolute equality, but for eliminating social and political inequality. Pointing out that certain living conditions, like terrain, will always be different and therefore unequal does nothing to demonstrate the impossibility of social or political equality.

This kind of response is what leads me to believe Engels really was just reacting to the word “equality” itself being included. Against this, we can also see his preferred alternative: the abolition of all class distinctions. But as I indicated above, Engels is overestimating how much of a difference this really is. Just like distinctions in terrain mark a certain kind of inequality, so do class distinctions. To call for the abolition of class distinctions therefore is to call for a kind of equality.

Despite this, Engels continues to rant against equality in his letter:

The concept of a socialist society as a realm of equality is a one-sided French concept deriving from the old “liberty, equality, fraternity,” a concept which was justified in that, in its own time and place, it signified a phase of development, but which, like all the one-sided ideas of earlier socialist schools, ought now to be superseded, since they produce nothing but mental confusion, and more accurate ways of presenting the matter have been discovered.

This framing demonstrates how Engels really believed he was doing something different. He did not consider “class abolition” to simply be another way of phrasing the same idea. Rather, the call for class abolition is meant to be a higher phase of development compared to calls for equality, which is considered to be inferior for being not only confusing but actually less accurate.

Why is equality more confusing and less accurate? We only have his above example to go by: absolute equality is impossible because there will always be some kinds of inequalities, like in terrain. On this ground, Engels dismisses any framing of socialism as a “realm of equality.” He disapproves of any call for eliminating a kind of inequality, and wants this to be “superseded” by calls for eliminating a kind of distinction. But this is itself a distinction without a difference. He is presenting a rhetorical break as a theoretical one.

Engels also makes sure to highlight the superiority of this phrase, but to also associate the connection between socialism and equality with the French. Undoubtedly the French republican motto of “liberty, equality, and fraternity” represents a very popular expression of Enlightenment values and political radicalism of the time. But Engels is not merely giving a history lesson, but showing the way that German socialism is meant to be surpassing French socialism. Marx and Engels were extremely competitive against French influence on the socialist movement, including thinkers like St. Simon and Fourier. But Proudhon especially became a figure they wanted to combat. An example of this can be seen in Marx’s letter to Engels from July 1870, mere months before the Paris Commune began:

The French need a thrashing. If the Prussians win [the Franco-Prussian war], the centralisation of the state power will be useful for the centralisation of the German working class. German predominance would also transfer the centre of gravity of the workers' movement in Western Europe from France to Germany, and one has only to compare the movement in the two countries from 1866 till now to see that the German working class is superior to the French both theoretically and organisationally. Their predominance over the French on the world stage would also mean the predominance of our theory over Proudhon's, etc.

Engels similarly looked for ways to combat the influence of Proudhon and French socialism in favor of German socialism, as revealed earlier in the letter to Bebel:

We would therefore suggest that Gemeinwesen ["commonalty"] be universally substituted for state; it is a good old German word that can very well do service for the French “Commune.”

That one didn’t really catch on, Engels.

Given the above, it strikes me as plausible that one of the motivating factors behind Marx and Engels’ war against equality was to limit the spread of French influence, perhaps especially of Proudhon, by creating a rupture with them in terms of jargon. This is speculation on my part, but it is indisputable that Engels had anarchists (namely Bakunin, who Engels saw as just expressing “a mixture of communism and Proudhonism”) in mind while writing his critique because he says so directly in the very next paragraph of his letter:

Remember that abroad we are held responsible for any and every statement and action of the German Social-Democratic Workers’ Party. E.g. by Bakunin in his work Statehood and Anarchy, in which we are made to answer for every injudicious word spoken or written by Liebknecht since the inception of the Demokratisches Wochenblatt. People imagine that we run the whole show from here, whereas you know as well as I do that we have hardly ever interfered in the least with internal party affairs, and then only in an attempt to make good, as far as possible, what we considered to have been blunders — and only theoretical blunders at that.

Marx’s Critique of the Gotha Programme

Marx addressed this same section as Engels’ within his own Critique of the Gotha Programme, although he did so even more briefly:

Instead of the indefinite concluding phrase of the paragraph, "the elimination of all social and political inequality", it ought to have been said that with the abolition of class distinctions all social and political inequality arising from them would disappear of itself.

This is a far superior answer compared to Engels. Firstly, Marx correctly identifies that the program called for social and political equality, rather than absolute equality. He therefore avoids Engels’ non sequitur. Secondly, he connects the call for social and political equality to the call for the abolition of class distinctions in a more interesting way.

By the framing here, social and political inequality is considered to be a separate matter from class distinctions. Rather, they are kinds of inequalities that arises from class distinctions, at least in part, and the workers’ main interest in them is limited to the extent that this is true. It also implies that our attention should be focused primarily, perhaps even exclusively, on class itself, trusting that issues of social and political inequality will be solved “of itself” once we combat the root issue.

Depending on how we interpret this, it isn’t necessarily wrong, but does seem to at least first with a kind of class reductionism. I find it doubtful, for example, that abolishing class will automatically lead to the end of social inequalities like patriarchy. Likewise, these forms of hierarchy and authority are often mutually reinforcing, meaning we cannot fight against systems of class distinctions like capitalism without simultaneously fighting the government, racism, colonialism, patriarchy, homophobia, transphobia, etc.

As socialists, we therefore cannot be satisfied with saying that once we abolish class the rest will work itself out, not only because it will not do so, but because we will not succeed in abolishing classes without combating these other forms of oppression along the way, just as we cannot succeed in defeating these issues without also addressing class. Still it is technically not wrong that by abolishing class distinctions we would also abolish inequalities insofar as they arise from class.

For our purposes, the more important point here is how Marx is dealing with the concept of equality. By this framing, we can see that a socialist society would be a more equal one, since it does imply the disappearance of other social and political inequalities to some extent, although perhaps not entirely. But just like Engels, Marx seems to be substituting a call for equality with a call for class abolition, which is not directly recognized as a kind of equality itself.

This tactic of clarifying calls for equality, or perhaps even neutralizing them if Marx thinks they are off base, is a pattern we can see elsewhere too. For example, the General Rules of the International Workingmen’s Association drafted by Marx indicates that “the struggle for the emancipation of the working classes means not a struggle for class privileges and monopolies, but for equal rights and duties, and the abolition of all class rule”. While at first this seems like Marx endorsing a kind of equality, he elsewhere dismissed it as a concession. He wrote to Engels regarding these rules that “All my suggestions were adopted by the subcommittee. I was compelled to insert into the Constitution some phrases about 'rights' and 'duties,' as well as 'truth, morality, and justice' but all this is so placed that it is not likely to bring any harm.”2 Presumably the reason why it is unlikely to do any harm is precisely because it is placed right next to a call for abolishing all class rule. Far from being an endorsement from Marx for a kind of equality, we have yet another example of how he tried to neuter these calls.

We can get a better sense of why Marx disapproved of calls for “equal rights” thanks to an earlier part of his Critique of the Gotha Programme, which deals with the programme’s declaration that “the proceeds of labor belong undiminished with equal right to all members of society.” Marx took several issues with this phrase, such as it claiming this for all members of society, including non-workers, while also promising “undiminished” proceeds of labor. But even this idea of the “proceeds of labor” is itself objectionable because, when the means of production are commonly owned, there would be no market-exchange, nor would labor appear as “value” in the product. The only time something like this could apply is in the early phases of communism, just after the workers take control of the means of production but are still “stamped with the birthmarks” of capitalism, and replicate some of its logic within their own institutions until it could develop new ones. This would include distributing consumption goods to the individual worker according to the amount of labor they contribute, represented by a ticket indicating how many hours of work has been done so that an equivalent amount can be “purchased.”

Here, obviously, the same principle prevails as that which regulates the exchange of commodities, as far as this is exchange of equal values. Content and form are changed, because under the altered circumstances no one can give anything except his labor, and because, on the other hand, nothing can pass to the ownership of individuals, except individual means of consumption. But as far as the distribution of the latter among the individual producers is concerned, the same principle prevails as in the exchange of commodity equivalents: a given amount of labor in one form is exchanged for an equal amount of labor in another form.

Hence, equal right here is still in principle – bourgeois right, although principle and practice are no longer at loggerheads, while the exchange of equivalents in commodity exchange exists only on the average and not in the individual case.

This is an interesting example of a danger Marx sees in calling for equal rights. In this case, by maintaining “equal right” we are maintaining the logic of capitalism where value is measured according to socially necessary labor time. This is why it is “bourgeois right,” even when there is no more bourgeoisie!3 Focusing too much on this “equal right” hinders us from developing a superior system that isn’t using this standard of labor-time to begin with.

Marx indicates some of the limits as he goes on.

In spite of this advance, this equal right is still constantly stigmatized by a bourgeois limitation. The right of the producers is proportional to the labor they supply; the equality consists in the fact that measurement is made with an equal standard, labor.

But one man is superior to another physically, or mentally, and supplies more labor in the same time, or can labor for a longer time; and labor, to serve as a measure, must be defined by its duration or intensity, otherwise it ceases to be a standard of measurement. This equal right is an unequal right for unequal labor. It recognizes no class differences, because everyone is only a worker like everyone else; but it tacitly recognizes unequal individual endowment, and thus productive capacity, as a natural privilege. It is, therefore, a right of inequality, in its content, like every right. Right, by its very nature, can consist only in the application of an equal standard; but unequal individuals (and they would not be different individuals if they were not unequal) are measurable only by an equal standard insofar as they are brought under an equal point of view, are taken from one definite side only – for instance, in the present case, are regarded only as workers and nothing more is seen in them, everything else being ignored. Further, one worker is married, another is not; one has more children than another, and so on and so forth. Thus, with an equal performance of labor, and hence an equal in the social consumption fund, one will in fact receive more than another, one will be richer than another, and so on. To avoid all these defects, right, instead of being equal, would have to be unequal.

Marx objects to “equal right” according to labor contributed for two primary reasons in this section. Firstly, some people are able to work longer or harder compared to other workers thanks to natural differences in ability. If we distribute according to labor then, then they can enrich themselves this way thanks to a mere accident of birth, amounting to a kind of “natural privilege.” Secondly, since this system only considers the individual as a worker, it must ignore other aspects of people’s lives that might cause greater need. We can also notice some other comments, like Marx’s offhand mention that how different people must be unequal in some respect to be different, lining up with Engels’ point from his letter, but here given far less weight as an insight.

Anyway, Marx identifies these points as “bourgeois limitations.” They are bourgeois because they are adopting capitalism’s view of measuring value in terms of labor time. But they are limitations or defects with respect to a system aiming at the “full and free development of each.” As communism develops on its own foundations instead of adopting and repurposing those from capitalism in its early stages, and as it develops its own productive capacity, it can surpass these limitations.

But these defects are inevitable in the first phase of communist society as it is when it has just emerged after prolonged birth pangs from capitalist society. Right can never be higher than the economic structure of society and its cultural development conditioned thereby.

In a higher phase of communist society, after the enslaving subordination of the individual to the division of labor, and therewith also the antithesis between mental and physical labor, has vanished; after labor has become not only a means of life but life's prime want; after the productive forces have also increased with the all-around development of the individual, and all the springs of co-operative wealth flow more abundantly – only then can the narrow horizon of bourgeois right be crossed in its entirety and society inscribe on its banners: From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs!

Much can be said and has been said about this section. The final phrase is particularly famous, although it is not actually original to Marx.

We can see how this higher phase is surpassing the limits of the first phase. Instead of matching how much each gets to what they contribute, people contribute and take from the system as their own pleasure. Each person contributes “according to his ability” because labor itself has been made enjoyable as “life’s prime want.” There is no need to coax people into working by the promise of compensation because it is pursued for its own sake. Instead of paying people to work then, things are distributed according to need. Products are considered primarily as use-values, and are distributed directly to the satisfaction of what people need them for. The limits and defects that existed before where we might distribute less to some despite them having greater need is overcome.

Can this be considered a system of equality? In a way, yes. There is still a clear proportionality being described here, as the amount each contributes is equal to their ability, and the amount each receives is equal to their need. It may be misleading to focus too much on this as a principle though, precisely because it is describing this disconnect between what each does and what they receive. There is enough made from easy enough work that questions of distribution are essentially trivial. If we want to present this as a kind of “equal right,” then the tricky part is not demonstrating that it is equal, but that it is a “right” at all.

But just as Proudhon argued that “equality of comfort” is “the business of the laborers to achieve for themselves, when provided with equal means,” Marx similarly thinks these questions about distribution are secondary to questions about production, which in communism is seen in the common ownership of the means of production. These two phases of communism are distinguished by how thoroughly production is transformed on this basis. As Marx indicates, a prerequisite for this higher phase is eliminating the domination of the division of labor, transforming labor into something pleasant pursued for its own sake, and reaching a high level of abundance through cooperation. This is two levels of maturity for the same mode of production.4

A potential issue exists here though for how much conditions could be realized. Could all labor be made pleasant so as to not need to be divided or compensated? Can production reach a high enough level that people could receive as much as they need without recourse to labor-time accounting? If it cannot be eliminated entirely and only reduced to some minimum, would we still be justified in calling this a “bourgeois” right or limitation? I would think not, but as Marx is emphasizing, this is all ultimately secondary since these are questions of distribution, not production:

I have dealt more at length with the "undiminished" proceeds of labor, on the one hand, and with "equal right" and "fair distribution", on the other, in order to show what a crime it is to attempt, on the one hand, to force on our Party again, as dogmas, ideas which in a certain period had some meaning but have now become obsolete verbal rubbish, while again perverting, on the other, the realistic outlook, which it cost so much effort to instill into the Party but which has now taken root in it, by means of ideological nonsense about right and other trash so common among the democrats and French socialists.

Quite apart from the analysis so far given, it was in general a mistake to make a fuss about so-called distribution and put the principal stress on it.

Any distribution whatever of the means of consumption is only a consequence of the distribution of the conditions of production themselves. The latter distribution, however, is a feature of the mode of production itself.

In this section we can see just how quickly Marx is to dismiss calls for equal rights, and how, like Engels, he dismisses it for being outdated and French. However, the emphasis here seems to be placed, not on equality in general, but on “equal rights,” particularly to the extent this is focused on the distribution of goods meant for individual consumption. The danger of importing bourgeois notions of equality is well taken, as is the desire to surpass the limitations, bourgeois or otherwise, that make systems of distribution necessary.

But it’s not clear that these are issues with calls for equality generally, especially when, if we turn our focus and stress on the conditions of production as Marx instructs us to, we do see a clear equality found in the common ownership of the means of production and the abolition of the inequality of class distinctions. While Marx may not be particularly motivated by notions of equality, he seems to advocate for at least this form nevertheless.

Engels’ Anti-Dühring

Engels’ views on equality would develop over the years, and he offers a much more in-depth and nuanced discussion in his 1877 book Anti-Dühring. This was a lengthy critique of another German socialist named Eugen Dühring, and became especially popular work for turning the writings of Marx and Engels into a holistic system of “Marxism.”5

In Part 1 Chapter 10, after dismissing Dühring’s argument, Engels provides a lengthy account of the history of equality and how it has been presented in different ways throughout history. This includes covering Greek and Roman conceptions of equality even as they divided people between freeman and slaves, and in Christianity with the doctrine of original sin. That different political groups advocate for and develop distinct notions of equality is something we saw Aristotle himself point out before, so this is hardly surprising.

The more interesting part is Engels’ elaboration on the bourgeois notion of equality, distinctive to them as a class and offered as a way to challenge the feudal system. We already got a sense of this from Marx’s Critique of the Gotha Programme, but it is elaborated with a more complete historical account here. To make large-scale trade possible, especially on an international level, there needed to be unrestricted movement and similar laws across countries. The bourgeoisie also required the existence of a proletariat freed from guilds that could be readily hired as wage-laborers, free to sign contracts. And of course their entire system depended on the circulation of capital, and therefore a market system attempting to exchange equal values. As the feudal system was unable to accommodate all of these changes to the bourgeoisie’s satisfaction, once they had gained sufficient power they called for political revolutions, with accompanying demands for equality.

But this same process and demand for equality can be seen in the proletariat that accompanies the bourgeoisie:

As is well known, however, from the moment when the bourgeoisie emerged from feudal burgherdom, when this estate of the Middle Ages developed into a modern class, it was always and inevitably accompanied by its shadow, the proletariat. And in the same way bourgeois demands for equality were accompanied by proletarian demands for equality. From the moment when the bourgeois demand for the abolition of class privileges was put forward, alongside it appeared the proletarian demand for the abolition of the classes themselves — at first in religious form, leaning towards primitive Christianity, and later drawing support from the bourgeois equalitarian theories themselves. The proletarians took the bourgeoisie at its word: equality must not be merely apparent, must not apply merely to the sphere of the state, but must also be real, must also be extended to the social, economic sphere. And especially since the French bourgeoisie, from the great revolution on, brought civil equality to the forefront, the French proletariat has answered blow for blow with the demand for social, economic equality, and equality has become the battle-cry particularly of the French proletariat.

This is a far less antagonistic presentation of the proletariat’s call for equality compared to what was saw earlier. I could see the ways this might be read as a recognition that class abolition really is itself a form of equality, rather than a distinct “true meaning” hidden beneath calls for equality. However, having seen Marx and Engels’ comments elsewhere, I don’t think this marks a shift in their thinking. This is still just describing the call for equality as a “phase of development” in the move towards the call for class abolition.

This is especially made clear in the next paragraph as Engels elaborates on what the proletariat mean by calling for equality.

The demand for equality in the mouth of the proletariat has therefore a double meaning. It is either — as was the case especially at the very start, for example in the Peasant War — the spontaneous reaction against the crying social inequalities, against the contrast between rich and poor, the feudal lords and their serfs, the surfeiters and the starving; as such it is simply an expression of the revolutionary instinct, and finds its justification in that, and in that only. Or, on the other hand, this demand has arisen as a reaction against the bourgeois demand for equality, drawing more or less correct and more far-reaching demands from this bourgeois demand, and serving as an agitational means in order to stir up the workers against the capitalists with the aid of the capitalists’ own assertions; and in this case it stands or falls with bourgeois equality itself. In both cases the real content of the proletarian demand for equality is the demand for the abolition of classes. Any demand for equality which goes beyond that, of necessity passes into absurdity.

As we can clearly see here, there are meant to be two meanings of equality “in the mouth of the proletariat”:

Criticizing a list of social inequalities, especially inequalities of wealth, station, and

Turning the bourgeois calls for equality against them.

Neither of these are directly a call for class abolition. Rather, the abolition of classes is meant to be the “real content” of both demands. Engels is still not recognizing class abolition or the common ownership of the means of production as forms of equality. He even rules out any such interpretation by declaring that any demand for equality beyond the two forms as an absurdity.

Certainly the proletariat’s calls for equality do take these forms as well. Between the two forms, the first gets the closest to recognizing class abolition as fixing an inequality. However, from the examples given, it is clear that Engels has questions of distribution in mind here, not production. This can be more accurately interpreted as dealing with inequalities that extend from classes. It is therefore an equivalent to Marx’s suggested revision to the Gotha Programme that “with the abolition of class distinctions all social and political inequality arising from them would disappear of itself.” This can be seen in Engels describing this call for equality as a reflection of the proletariat’s “revolutionary instinct.” The specific forms of equality they are railing against, as they are not calling for absolute equality, are ones that develop from class distinctions.

The other use of equality is even further removed, focusing on the ways to call out the bourgeoisie on their hypocrisy. Hence the reason this use “stands or falls with bourgeois equality itself.” It is not a genuine proletarian idea, but something used for agitation. Proudhon appears like an example par excellence here given his critique of defenses of property in chapters 2 and 3 of What is Property.

Engels not only gives these as the two meanings of equality for the proletariat, but as the only two possible meanings, declaring that any attempt to demand equality besides these limited calls will pass “into absurdity.” Even if we interpreted this charitably and decided Engels meant beyond the call for class abolition, this would still be wrong because the proletariat not only wants to get rid of classes, but establish the common ownership of the means of production. This will be a real equality, with different individuals being equal to each other with regard to their relation to the means of production, and it will be an enduring equality that defines socialism long after classes are abolished.6

Bakunin: Liberty In Equality

Revolutionary Catechism

Our final examination of equality in early socialism will be with the Russian anarchist Mikhail Bakunin. Like Proudhon, Bakunin believed that liberty can only be achieved based on the principle of equality. Among other things, the freedom of each depends on the freedom of all, identifying a kind of unity between individual and collective freedom that is also found in Marx and Engels.

Despite this apparent agreement, Bakunin came into fierce conflict with Marx and Engels within the First International, and one of their first major disputes was over how he advocated for equality. Analyzing this conflict can help to reveal both positions a bit more clearly.

Before we examine that conflict, we should become familiar with Bakunin’s own stance on equality more directly. This can be seen in his Revolutionary Catechism (1866):

4. It is quite untrue that the freedom of the individual is bounded by that of every other individual. Man is truly free only to the extent that his own freedom, freely acknowledged and reflected as in a mirror by the free conscience of all other men, finds in their freedom the confirmation of its infinite scope. Man is truly free only among other equally free men, and since he is free only in terms of mankind, the enslavement of any one man on earth, being an offence against the very principle of humanity, is a denial of the liberty of all.

5. Every man’s liberty can be realized, therefore, only by the equality of all. The realization of liberty in legal and actual equality is justice.

The first type of equality that Bakunin emphasizes here is a kind of “equality of freedom,” shared by equally free men and women. It is interesting here because this kind of equality is not presented as merely incidental, but a consequence of freedom existing systematically. The freedom of all is a prerequisite for the freedom of each because they share in the liberty of others. There is a kind of unity between individual and collective liberty.

Marx and Engels shared similar ideas. According to chapter 2 of the Communist Manifesto, what they are ultimately after is “an association, in which the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all.” Some have wrongly presented the conflict between Bakunin and Marx as one of individual freedom vs collective freedom respectively. Here we can see how misguided this is, as both emphasize the deep connection between the two concepts. Marx claims in Capital that communism will be “a society in which the full and free development of every individual forms the ruling principle,” while Engels claims in Anti-Dühring that “It goes without saying that society cannot free itself unless every individual is freed.” Bakunin seems to mostly be challenging Marx and Engels here in calling this relation a kind of equality, which again seems like the opposite of what most would expect their conflict to be about.

This kind of freedom and equality should presumably consist of at least two things. The firstly, and what we see emphasized here, is freedom as an absence of authority. For anarchists, as I emphasized in Read On Authority, this absence of authority especially denotes an absence of imposed relations of domination or exploitation, rights to command, or similar privileges backed by some form of power. This sense of freedom would be closely tied to the abolition of class distinctions, as well as other forms of oppression (e.g. racism, sexism, etc.).

But freedom implies not only an absence of oppression, of unfreedom. It requires not only a negative expression, but a positive one in a kind of real opportunity to do or to be something. Here too Bakunin calls for a kind of “freedom through equality” or “liberty in equality.”

This, once again, could not be understood in an absolutist sense. Some opportunities will always be distinct. As Engels pointed out, the “living conditions of Alpine dwellers will always be different from those of the plainsmen.” The opportunity to hike a mountain or learning to surf will always be unequal between people to a certain extent.

But Bakunin does find a kind of positive equality compatible with this notion of freedom precisely where we would expect it: in the collective ownership of the means of production. We see this as he continues.

10. Social organization. Without political equality there is no true political liberty, but political equality will only become possible when there is economic and social equality.

10 (a). Equality does not mean the levelling down of individual differences, nor intellectual, moral and physical uniformity among individuals. This diversity of ability and strength, and these differences of race, nation, sex, age and character, far from being a social evil, constitute the treasure-house of mankind. Nor do economic and social equality mean the levelling down of individual fortunes, in so far as these are products of the ability, productive energy and thrift of an individual.

10 (b). The sole prerequisite for equality and justice is a form of social organization such that each human individual born into it may find — to the extent that these are dependent upon society rather than upon nature— equal means for his development from infancy and adolescence to coming of age, first in upbringing and education, then in the exercise of the various capacities with which each is endowed by nature. This equality at the outset, which justice requires for all, will never be feasible as long as the right of succession survives.

The foundation of liberty and any further equality then is rooted in these “equal means for his development.” The real possibility for the “full and free development of every individual,” as Marx put it, is found in this common ownership of the means of production. There are no longer social impediments to accessing these resources as they are no longer monopolized and are available for the use of all.

But beyond this, Bakunin also emphasizes that, to provide real opportunity, people need to have adequate training, education, and care before they actually use them fully once matured. He therefore also emphasizes this equality extending throughout an entire lifespan, from cradle to grave, marking a fully free society.

This system of equality is therefore especially clear when we contrast it to systems of inequality established from birth, especially seen in the system of inheritance, where thanks to property, have privilege from birth, with access to greater opportunities and luxury.

Like Marx and Engels, Bakunin did not believe this established absolute equality, including the abolition of certain natural inequalities in the diversity of mankind. Also like Marx though, Bakunin expected these problems to diminish over time as we reach higher phases of socialism.

10 (g). Once the inequality produced by the right of inheritance has been abolished, there will still remain (but to a far lesser degree) the inequality that arises from differences in individual ability, strength and productive capacity— a difference which, while never disappearing altogether, will be of diminishing importance under the influence of an egalitarian upbringing and social system, and which in addition will never weigh upon future generations once there is no more right of inheritance.

With these points together, Bakunin is able to summarize these notions of equality together. Against the class system, seen in its most complete and separate form when it exists from birth, socialism can exist as a realm of opportunity and freedom precisely because it is built on equality found in the collective ownership of the means of production. To exist fully as an enduring system, this also means making sure children have proper care and education so they can take full advantage of these resources when mature. He concludes like this:

12 (a). The aim of democratic and social revolution can be summarized under two headings.

Politically, it is the abolition of historic rights, the right of conquest and the law of diplomacy. It is the complete emancipation of individuals and associations from the yoke of divine and human authority, the absolute destruction of all compulsory unions and amalgamations of communes into provinces, provinces and conquered lands into the State, and lastly the radical dissolution of the centralist, custodial, authoritarian State, with all its military, bureaucratic, administrative, judicial and civil institutions. In other words, the restoration of liberty to all— individuals, collective bodies, associations, communes, provinces, regions and nations alike— and mutual safeguard of that liberty through federation.

Socially, it is the confirmation of political equality through economic equality. It is equality— not natural but social —for every individual at the start of his or her career, which means equality of maintenance, upbringing and education for every child until the age of majority.

The Alliance and the Equality of Classes

From what we have seen so far, it seems like the conflict between Marx and Engels against Proudhon and Bakunin is largely a matter of rhetoric and framing. Everyone involved here believes the most important aspect of socialism is the abolition of classes and establishing the common ownership of the means of production. The anarchists recognize this as a move towards equality, terms which Marx and Engels seem to intentionally avoid despite there being a clear sense where it is correct. Some debate may exist over equality that extends beyond that, such as whether we could describe a kind of “equality of wages,” but this is considered secondary by everyone involved too.

If this were merely a disagreement in jargon, it would have some interest and should be pointed out to avoid confusion, but that would largely settle matters. However, the actual fight between Marx and Engels against Bakunin became much more vicious than this, especially within the International Workingmen’s Association (IWA), better known today as the “First International.”

The International had been a pluralistic organization made up of various worker associations from various nations, as the name implies, that all shared the same end of “the protection, advancement, and complete emancipation of the working classes.” It marked one of the great early attempts to fulfill the call for the workers of the world to unite.

Both Marx and Engels were members of the IWA’s General Council and played a central role in different associations being admitted. Bakunin had formed one such organization, the International Alliance of Socialist Democracy, which was largely made up of members who had split from the anti-war League of Peace and Freedom. At its founding, its program included this provision:

It [the Alliance] desires above all the political, economic and social equalization of the classes and of the individuals of both sexes, commencing with the abolition of the right of inheritance, in order that in the future the enjoyment be equal to the production of each, and that, in accordance with the decision taken by the last Congress of the workers at Brussels, the earth, the instruments of labor, like all other capital, becoming the collective property of the entire society, can only be utilized by the laborers, that is by the agricultural and industrial associations.

Marx had a whole host of criticisms of this programs which he wrote in the margins, some of which are remarkably uncharitable, mocking, and deliberately obtuse, such as saying that the call for the “equalization of… individuals of both sexes” was a call for a “Hermaphrodite man!” But especially important for the Alliance’s application into the Alliance was the call for the “the economic and social equality of classes and individuals.” Marx argued that this phrasing was actually a call for the “harmony of capital and labor,” and therefore was incompatible with class abolition, although he also admitted this appeared to only be a “slip of the pen.” This was relayed in letter on March 5, 1869:

With regard to the programme of the 'Alliance', therefore, it is not necessary for the General Council to submit it to an examen critique. The Council does not need to examine whether it is an adequate scientific expression of the workers' movement. It has only to ask whether the general tendency of the programme is in opposition to the general tendency of the International Working Men's Association—the COMPLETE EMANCIPATION OF THE WORKING CLASSES!

This reproach might apply to only one phrase in the programme, para. 2: 'elle veut avant tout l'égalisation politique, économique et sociale des classes.' ‘L'égalisation des classes', interpreted literally, is simply another way of saying the 'Harmonie du capital et du travail' preached by bourgeois socialists. The final aim of the International Working Men's Association is not the logically impossible 'égalisation des classes', but the historically necessary 'abolition des classes'. From the context in which this phrase appears in the programme, however, it seems to be merely A SLIP OF THE PEN. The General Council has little doubt, therefore, that this phrase, which might lead to serious misunderstanding, will be deleted from the programme.7

A key question here then is whether Marx is interpreting this phrase correctly. Certainly the phrase “harmony of capital and labor” really would contradict the goal of workers’ emancipation. This is not an implausible interpretation of “equality of the classes,” so for rhetorical reasons in a program it is not unreasonable to request this to be changed accordingly. In fact, Bakunin agreed that this could be clarified further and said as much even before this response letter was sent. On December 22, 1868, Bakunin wrote a letter to Marx in which gives an explanation of why it was used, while admitting it could have been phrased better:

I read in your letter to Serno that we have posed the question falsely at Berne, by speaking of the equalization of classes and individuals. – That observation is perfectly fair with regard to the terms, with regard to the formula that we have made use of. – But that formula has been, as it were, imposed on us by the stupidity and final impenitence of our bourgeois audience. – The have been stupid enough to yield to us, without a fight, as it were, the terrain of equality – and our triumph has consisted precisely in the fact that we have been able to observe that they reject all the conditions of a real and serious equality. – That if what has made them, and still makes them, furious. – What’s more, I admit wholeheartedly that we could have better expressed ourselves otherwise, if, for example, we had said: The radical suppression of the economic causes of the existence of the different classes, and the economic, social and political equalization of the environment and the conditions of existence and development for all individuals without difference of sex, nation and race.8 – I have send you in a bundle all the speeches, except one, that I gave at Berne

Bakunin recognized in equality not only a principle worth supporting, but because it was a rhetorical space surrendered to them by the bourgeoisie. This is because it is impossible for them to support “the conditions of a real and serious equality” precisely because this would undermine their very existence. Clearly Bakunin had a much stronger egalitarian instinct than Marx did. Because of this, Bakunin gives his improved version of this slogan in calling for the “radical suppression of the economic causes of the existence of the different classes,” which is equated with various forms of equality, focused especially on equalizing the “environment and the conditions of existence and development for all individuals”.

The reference to a speech in Berne shows Bakunin using the same language, but with a much longer elaboration on his meaning before the Alliance was even formed:

I have demanded, I do demand the economic and social equalisation of classes and individuals. Now I want to say what I mean by these words.

I want the abolition of classes both in an economic and social as well as a political sense. […] The history of the [Great French] Revolution itself and the seventy-five years that have passed since then show us that political equality without economic equality is a lie. However much you proclaim the equality of political rights, as long as the economic organisation of society splits it into different social strata, this equality is nothing but a fiction. To make it a reality, the economic causes of class differences must disappear – we must abolish the right to inheritance, which is the permanent source of all social inequalities. […] Thus, gentlemen, but only thus, shall equality and freedom become a political truth.

Here is what we mean when we speak of ‘the equalisation of classes’. Perhaps it would be better to speak of the abolition of classes, the unification of society by the abolition of economic and social inequality. But we have also demanded the equalisation of individuals, and this is the main thing that draws upon us all the wrath of our adversaries’ indignant eloquence.9

From the beginning then, Bakunin took the phrase “equalization of classes” to mean the same thing as the “abolition of classes,” since it involves abolishing the economic cause of the classes. However, he believed “equalization of classes” worked similarly as an expression, and he also called for the equalization of individuals who cannot be abolished. Thus the phrase was condensed together, even when elaboration might have given more clarity and avoided a misreading Bakunin himself had already foreseen.10 A slip of the pen indeed.

This type of awkwardness in language is still one we sometimes see today. The context I personally see it most frequently discussed is regarding the fight against patriarchy and transphobia, as some people contrast “gender equality” and “gender abolition” as goals. It is not uncommon for people who believe in abolition to nevertheless talk about equality, precisely because the kind of equality they are after here would eliminate the important ways people are being socially distinguished on these grounds.

Eventually, the Alliance did join the IWA, but after fulfilling two conditions. Firstly, it disbanded as an international organization. Secondly, it changed its program to avoid any discussion of the equality of classes, instead calling for “the final and total abolition of classes and the political, economic and social equalization of individuals of either sex.”11

Just because they made this change did not mean Marx let things go though. Despite recognizing this line as being, in his own words, a mere “slip of the pen,” he would continue to use Bakunin’s support for the “equality of classes” as a point of mockery or a sign of deep theoretical simplicity or duplicity. Marx had full access to Bakunin’s speeches and explanations for why he used this phrase, but preferred to show it as a major theoretical error rather than something that was, at worst, a “slip of the pen.”

In his “Confidential Communication on Bakunin” in 1870, Marx leveraged his position within the General Council to launch his polemical attacks against Bakunin as a rival, including the call for the equality of classes, and spinning out a grand conspiracy theory of his supposed intention to take over the International himself.12

It suffices to say that the program he proposed at the Bern Congress contained such absurdities as “equality” of “classes,” “abolition of the right of inheritance as the beginning of the social revolution,” etc. – senseless prattle, a garland of hollow notions which pretended to be chilling; in short, an insipid improvization designed to achieve a certain monetary effect.

[…]

Behind the back of the London General Council – which was informed only after everything was seemingly ready – he established the so-called Alliance des Democrates Socialistes. The program of this Alliance was none other than the one B. had proposed at the Bern Peace [League] Congress. Thus, from the outset, the Alliance showed itself to be a propaganda organization of specifically Bakuninist private mysticism, and B. himself, one of the most ignorant of men in the field of social theory, suddenly figures here as a sect founder. However, the theoretical program of this Alliance was pure farce. Its serious side lay in its practical organization. For this Alliance was to be an international one, with its central committee in Geneva, that is, under Bakunin’s personal direction. At the same time it was to be an “integral” part of the International Working Men’s Association.

Years later in November 1871, Marx similarly wrote in a letter to Friedrich Bolte this assessment of Bakunin:

His [Bakunin’s] programme was a superficially scraped together hash of Right and Left – EQUALITY Of CLASSES (!), abolition of the right of inheritance as the starting point of the social movement (St. Simonistic nonsense), atheism as a dogma to be dictated to the members, etc., and as the main dogma (Proudhonist), abstention from the political movement.

Marx either could not or would not recognize anarchism, as represented by Bakunin, as a real tendency growing within the worker’s movement. Its growing prominence was continually attributed to conspiracy on the part of Bakunin, and his theoretical work was not seriously engaged, with Marx going out of his way to deliberately misrepresent or overstate these types of disagreements, or even lying about what Bakunin called for (e.g. Bakunin did call for the abolition of the right of inheritance, but never as the “beginning” or the “starting point” of the social movement; these words were added by Marx).13

This conflict with Bakunin would grow increasingly large over the years, culminating in the expulsion of Bakunin and other anarchists through questionable means from the IWA at their Hague Congress in 1872. This split marks the formal beginning of revolutionary anarchism as a distinct socialist movement.

Conclusion

As much as Marx and Engels tried to distance the socialist movement from equality, they could not eliminate it entirely, even from their own description of things. Did they intend to? From my own survey of the literature, it’s not entirely clear. I am certainly not the first to notice that Marx and Engels avoided egalitarian frameworks or turns of phrase. That they also so frequently denounced equality for being a French value, and the clearly rivalry or even hatred they felt towards the French socialists, calls into question how much they were really motivated by theoretical concerns. The extremes and slander Marx resorted to against Bakunin on a matter he admitted was only a “slip of the pen” at worst especially highlights this tendency.

On the other hand, the term “equality” can be thrown around enough that, without carefully explaining the way in which things are meant to be equal, it really could lead to confusions. Marx and Engels do bring up real dangers for ways in which bourgeois notions of equality and justifications might be snuck into our own reasoning, unconsciously adopting their framing. However, this danger is perhaps exaggerated by them as well since, as Bakunin notes, the bourgeoisie largely don’t present themselves as champions of equality. This especially seems true today where, ironically, the propertarians like to present liberty and equality as opposite, with capitalism representing liberty and the Marxists ironically representing equality! Proudhon and Bakunin took similar care to make a distinction between the kinds of social inequalities they opposed against the more natural inequalities they expected to still exist or even supported as part of the diversity needed for life.

An important point made across the board is that, when we focus on socialism, we cannot focus merely on matters of distribution. I wouldn’t go so far as to say that distribution follows automatically from the system of production (even in capitalism, workers can fight for higher wages, for example), but it certainly must conform to its limits. By focusing on the abolition of class distinctions, we can attack the most fundamental inequality of capitalism. This can likewise let us focus on building a comparable basis for socialism in the collective ownership of the means of production, where workers can relate to one another as associates, as equals. Through this equality, we form the real basis for individual and collective human development, bringing us into a truly free world.

Thanks for reading! If you would like to support me, you can help buy me a Ko-Fi!

It is worth noting that Proudhon failed in this respect himself. Despite naming himself a “defender of equality,” he denied that this equality extended to women. See my comments on Chapter 5 of What is Property.

We can also contrast this to Lenin, who mistakenly believed that this was a matter of a state continuing to uphold “bourgeois law,” a phrase Marx does not use here, because this system assumes individual ownership of the individual means of consumption. This can be found in Chapter 5 of Lenin’s State and Revolution, and was rightly critiqued by Chris Wright’s Contra State and Revolution.

Lenin helped to popularize referring to the first phase of communism as “socialism,” reserving the name communism only for this higher phase in State and Revolution. This is misleading as we are not dealing with two separate system, but a single mode of production. This idea that we need to go through socialism before we can arrive at communism has grossly mislead many and justified a whole host of counter-revolutionary actions and movements.

See Michael Heinrich’s "Je ne suis pas marxiste" for more.

This conclusion is so natural that some later Marxists would read this into these exact texts. For example, consider Vladimir Lenin’s description of the movement from the lower phase of communism to the higher phase in State and Revolution: “Democracy means equality. The great significance of the proletariat's struggle for equality and of equality as a slogan will be clear if we correctly interpret it as meaning the abolition of classes. But democracy means only formal equality. And as soon as equality is achieved for all members of society in relation to ownership of the means of production, that is, equality of labor and wages, humanity will inevitably be confronted with the question of advancing further from formal equality to actual equality, i.e., to the operation of the rule "from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs".” We do not find Marx or Engels ever calling this “actual equality” though. When they did argue for equality (and I have argued they did because a call for abolishing distinctions, such as class distinctions, is really a call for equality), they did not explicitly recognize it as such. On this issue, Lenin appears to hold the correct position (if we ignore his questionable view of democracy), funnily enough, but mistakenly believes he is describing the position of Marx and Engels!

Just as Proudhon called for equality while not consistently applying it, noted in the footnote above, Bakunin likewise failed to consistently practice what he preached. See Zoe Baker’s “Bakunin was a Racist.”

Quoted in Wolfgang Eckhardt’s The First Socialist Schism, p. 4-5

Ibid, p. 4

See The First Socialist Schism, p. 40-45 for more details

See The First Socialist Schism, p. 19-20 for more on Marx adding these words. Also see Read On Authority by me for a detailed look at Engels’ polemical and superficial engagement with anarchism in “On Authority.”